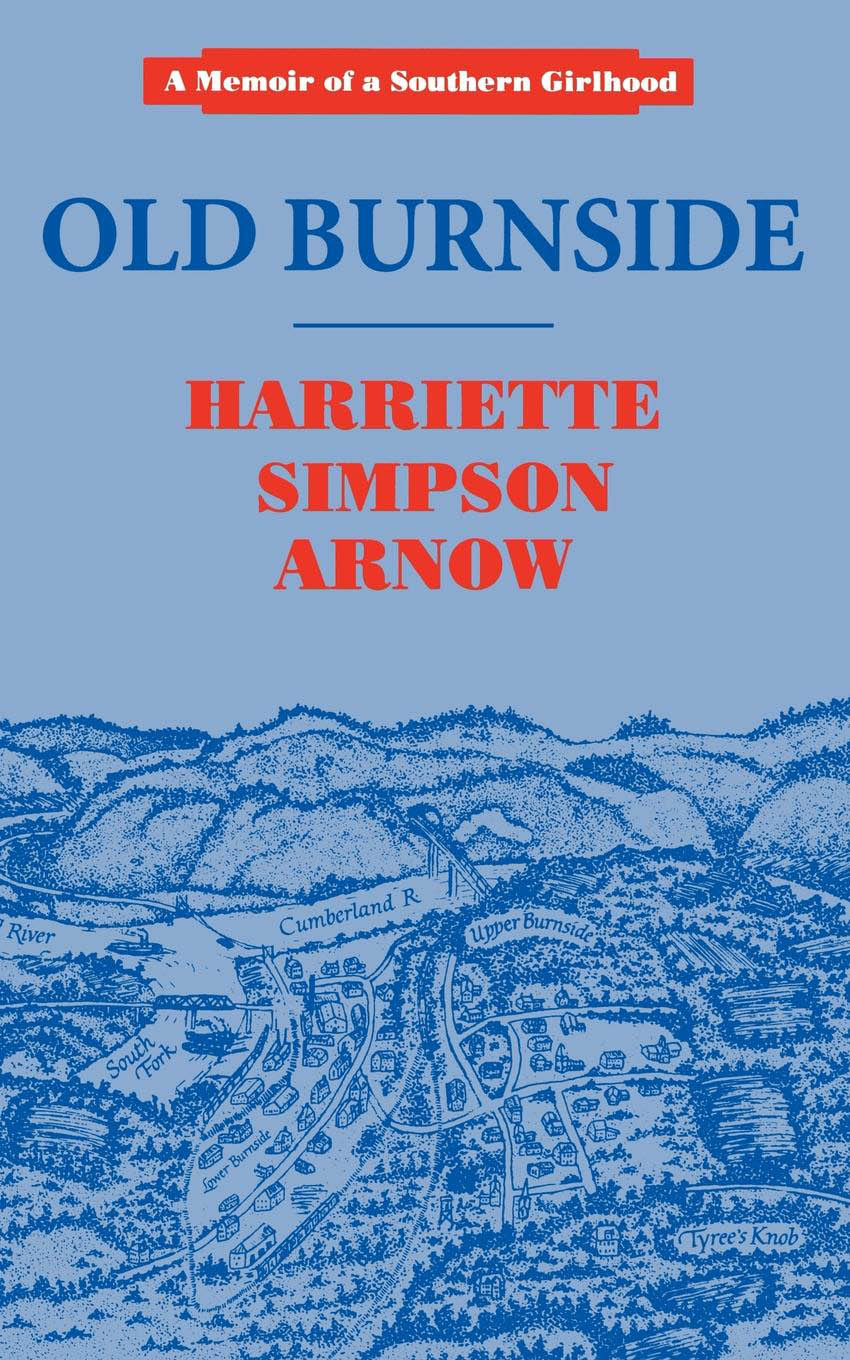

Old Burnside

Old

Burnside

HARRIETTE SIMPSON ARNOW

Copyright 1977 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8131-0860-5 (pbk.: alk. paper)

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of

American University Presses |

Contents

Prologue

ANN ARBOR SCHOOLS, like others in Michigan, have long observed Easter with a weeks vacation. During the Easter holiday of 1953, Husband took a week of his vacation in order to help take the children on the long-promised and overdue trip to see their grandmother Simpson at Burnside. Illness and vacations elsewhere had kept us away for more than three years. We would also see Lake Cumberland, one of the largest man-made lakes in the United States.

I had tourist material and newspaper clippings describing the dam, Lake Cumberland, and even the changes in Burnside. I knew Lake Cumberland began near the foot of Cumberland Falls and continued past Burnside and on down to Wolf Creek Dam, the largest earth-fill dam in the United States, over a mile long and 240 feet high. The lake it formed was 101 miles long with a shoreline of 1,255 miles. I thus knew everything and was ready to explain all to the children.

A few miles south of Somerset we came to a high bridge across a wide body of still water. Children, I said, this is what used to be Cumberland River; after Wolf Creek Dam was finished in 1950 it became Lake Cumberland.

Two voices came in chorus from the back seat: The sign said Pitman Creek.

I sat in silent confusion, looking ahead to find Burnside. The children were the sign watchers, the backseat drivers. We passed a line of garish bedspreads flapping in the wind as our daughter said, Cumberland River Bridge is just ahead. Were almost to Burnside.

We began to cross the long bridge. I could see little of the water near the bridge because of the head-high cement walls on either side of the two-lane road. Far away on the lake I could see here and there the same sort of pleasure craft I had seen in the Detroit River or Lake Erie. Was that point of land Bunker Hill or Bronston? It looked too low for either. I tried to remember the figures I had learned; when the lake was high, as it now appeared to be, the surface of the water was more than 150 feet higher than the average surface of Cumberland River at Burnside had been.

The bridge ended. We were going past the white limestone and red earth of recent excavations. I remembered I had planned to show the children the road to Bronston and tell them it led to Monticello where the stagecoaches used to stay except when they were traveling back and forth to Burnside. I began: Children, well soon be seeing the bridge across the South Fork to Bronston and Monticello. I remember.

Oh, Mother.

Oh, Mothers came frequently but with different meanings. I knew this one meant I had said something wrong. Our daughter continued, We passed a sign for Monticello before we crossed the last bridge.

Our son said, You mean Kentucky 90, dont you?

I didnt know. The roads out from Burnside used to have names, not numbers, but maybe the Monticello Pike was now Kentucky 90. We were stopping for a red light. There had never been a traffic light in Burnside. I looked out and up to the shoulder of a hill that rose above the town. That must be Tyrees Knob where I had spent my childhood and our mother continued to live. The shape was different; still, no other hill had risen close above upper Burnside, and the redbud and the dogwood were in bloom to make pink and white patches over the hill as they had used to do.

I looked on either side of the road and saw nothing familiar. The light changed. I saw a signSeven Gables Motel. That didnt mean anything. The building was nothing at all like the Seven Gables Hotel I had known in lower Burnside. Was this wide place in the road Burnside? A moment later I was certain. I saw a sign that said: Grissom and Rakestraw Lumber. There had been a Grissom and Rakestraw Lumber Company in lower Burnside for many years; Grissoms had lived in the town before it had a name.

Past the name I glimpsed stacks of lumber; then both were behind us as we went through a cut several feet deep and made a sharp turn that brought us to a stretch of road with no buildings on either side. I looked out the window to see the lake with a causeway that ended on the side of a round-topped hill. I knew Bunker Hill even with its feet cut off. Are you driving us to Tateville? I asked.

The question angered Husband. He had driven around Burnside more than I. You surely remember, he told me, that U.S. 27 before reaching Tateville climbed that steep hill out of Burnside.

Were on U.S. 27 South. Weve not been down in the valley. Our sign watchers sounded certain.

Traffic was heavy and fast, shoulders narrow. There was no turning back until we reached the parking space for a Tateville store. Nearing Burnside from the south, everybody saw the small sign that indicated the junction with another road, unnamed. We turned off here, though I was uncertain of our whereabouts. The cut and the curve for a new U.S. 27 had destroyed the homes that had stood above Antioch Road as it neared the lane I had walked on my way to and from school. Where was the lane?

I at last saw a familiar home ahead and knew we were on Antioch Road. The home belonged to Mrs. Robert Elinor whom I had known since early childhood. I wanted to stop and speak with her, but now that we were off the main road with no restaurant in sight, the children declared they were starving to death and must have food.

Husband said we couldnt burst in on my old mother with two hungry children expecting food at once.

He turned around and drove back to the Seven Gables Motel where he had seen a restaurant sign. I told him and the children that I wasnt hungry. I planned, while they were eating, to hunt Burnside on foot.

I crossed U.S. 27 and soon found the upper end of a street with its sidewalk cracked and broken by the roots of old beech and maples. I had known this street as a child, though I had never lived on it. I walked down this sidewalk until I could see across the way a white-painted house which I knew as the place where the Harry Waits had brought up their three children. I wondered if the little log house the elder Waits had built behind their home was still there. They had arranged on the log walls, in cases, and on tables the swords and several varieties of firearms their ancestors had used in colonial wars, the American Revolution, the War of 1812, and later conflictsall that for the school children and others curious to know what weapons their forebears had used.