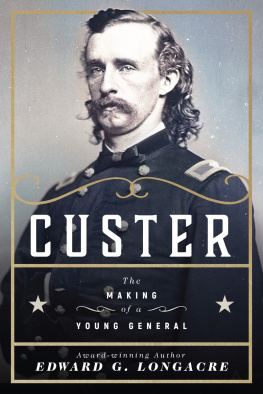

C USTERS R OAD TO D ISASTER

The Path to Little Bighorn

K EVIN M. S ULLIVAN

Copyright 2013 by Kevin M. Sullivan

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, PO Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

TwoDot is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press and a registered trademark of Morris Book Publishing, LLC.

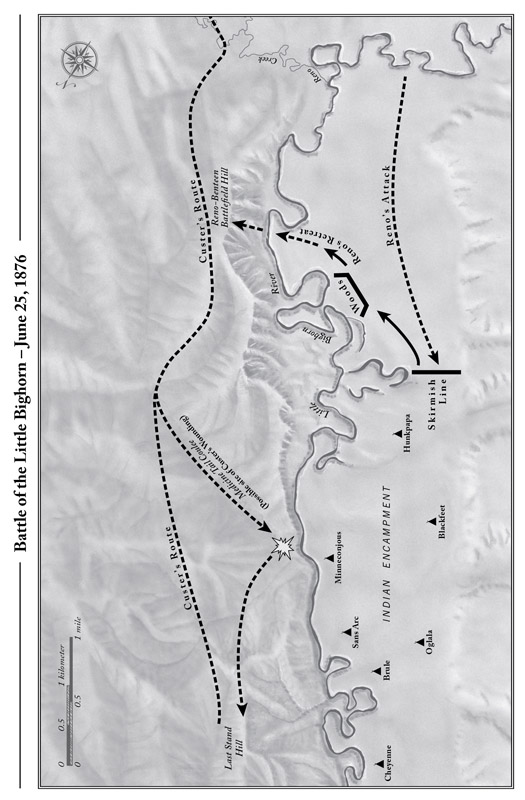

Map by Melissa Baker Morris Book Publishing, LLC

Project editor: Meredith Dias

Layout: Melissa Evarts

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sullivan, Kevin M., 1955

Custers road to disaster : the path to Little Bighorn / Kevin M. Sullivan.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7627-9474-4

1. Custer, George A. (George Armstrong), 1839-1876. 2. Little Bighorn, Battle of the, Mont., 1876. 3. GeneralsUnited StatesBiography. 4. United States. ArmyBiography. I. Title.

E467.1.C99S85 2013

973.8'2092dc23

[B]

2012036984

For my grandson,

Connor Jackson Ludwig

C ONTENTS

A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

Whenever anyone undertakes to write about the important events of those who are long dead, I believe it is very important to remember those who have gone before us, who have diligently documented the facts and circumstances that surrounded those lives. Without these individuals, much of what we call history would forever be lost to us, and the researcher would have virtually nowhere to go. To the many fine people who contributed to recording the events surrounding the life of George Armstrong Custer, from field reporters to established authors, I thank you. To those among the living who aided me in my search, I am indebted to you in ways you cannot imagine, for in some cases we exchanged words without exchanging names.

I would like to thank specifically the folks at the Armor Library at Fort Knox, Kentucky (now located at Fort Benning, Georgia), for their fine help and assistance. A big round of applause to the fine individuals in the research department at the Louisville Free Public Library, especially those who were forced to retrieve a number of old, dust-covered government publications that hadnt been used in years. I am also indebted to Ms. Sharon A. Small, museum specialist at Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, who worked very hard to get me the photographs I needed during a period of transition for the museum. Thanks also to Retired Lieutenant General Harold G. Moore, coauthor of the book, We Were Soldiers Once... and Young, and the late Brian C. Pohanka, for their very kind words regarding my previous work on George Custer. I would also be remiss if I didnt mention my friend and fellow writer, Ron Franscell, and the pivotal part he played in connecting me with Erin Turner of Globe Pequot Press.

And finally, I would like to offer my eternal gratitude to my wife, Linda Sullivan, who has been with me for every literary journey and working trip, always there to encourage me and offer her assistance in any way possible. With her at my side, the research and writing experience for each book has been an absolute joy.

P REFACE

Much has changed in the world since that day in June 1876 when George Armstrong Custer and five companies of his Seventh Cavalry perished under a broiling Montana sun. Many conflicts, great and small, have occurred over the last 137 years, filling the history books with the names of winners and losers from around the globe. Yet for many Americans, the Battle of Little Bighorn has continued to hold a unique place within our national psyche despite this passage of time. One can study bloodier battles, engaging larger armies and lasting far longer than that which occurred between the US military and the Native Americans on that day. Yet this battle is unique for a number of reasons, all of which would continue to produce changes for both cultures long after the smoke of battle had drifted away from the field.

First, the Indians were under no illusions concerning the final outcome in that summer of 1876, yet they were like anyone else who cherishes freedom and has no desire to go gently into that good night. And so, when Custer came looking for battle, they did not disappoint him. While the defeat of Custer must be considered their greatest victory against the whites, it would be bittersweet, for it would signal quite clearly the beginning of the end of their way of life. After Little Bighorn, a new, determined sense of wrath was kindled among those who sought to end what they considered to be a problem long overdue to be solved. It would be a pivotal battle, destined to radically change both cultures.

In one fell swoop the Sioux and Cheyenne warriors shattered the myth of Custer as the unconquerable warrior. The death of George Armstrong Custer ended the life of one of the most flamboyant, brave, careless, and fascinating characters to ever wear a US military uniform. His dramatic rise during the Civil War to the brevet (or temporary) rank of brigadier general at the tender age of twenty-three, and his uncanny ability to stay alive regardless of how recklessly he flung himself at the enemy, gave rise to his image as an almost mythical figure. Even President Lincoln had heard about this dashing young warrior whose name had become a household word. General Sheridan was so pleased with him that after General Grant and General Lee had signed the formal papers of surrender at Appomattox, Sheridan purchased the table upon which the documents had been signed and gave it to Custer as a gift for his wife. Forever after, Custer would be seen as the darling of the nation. More than anything else, he would be remembered by his generation as the boy general who went from victory to victory, whose life was filled with such good fortune that the term Custers Luck was used to refer to an unusually fortuitous event.

Yet if Custer could rise today from his tomb at West Point, he would be horrified to know that his fame, just a little over a century later, would spring from this very quick battle that resulted not only in his death, but in one of the worst military defeats in US history. Not a great legacy, to be sure, but history never promised it would be kind in remembering us, only to remember.

But what really happened at Little Bighorn, and what thoughts were spilling from the mind of Custer on that fateful day? For Custer, the idea that his beloved Seventh Cavalry would ever be defeated by an untrained, undisciplined, and unorganized group of Plains Indians had never entered his mind. Such arrogant heads had been raised in the US military before, only to be lopped off by untrained, undisciplined, and unorganized (but very determined) warriors.

When, on June 25, 1876, the scout Bloody Knife told Custer that there were more Sioux awaiting them than they had bullets, he merely responded, Well, I guess well get through them in one day. This expectation would evaporate before Custers eyes in little more time than it takes one to consume a meal, according to one Indian participant.