ALSO BY JOHN DARNTON

Black and White and Dead All Over

The Darwin Conspiracy

Mind Catcher

The Experiment

Neanderthal

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

Published by Alfred A. Knopf

Copyright 2011 by Talespin, Inc.

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada

by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks

of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Harold Ober Associates

for permission to reprint an excerpt from Sunday: New Guinea

by Karl Shapiro, copyright 1943, 1970 by Karl Shapiro.

First published in Good Housekeeping. Reprinted by permission

of Harold Ober Associates.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Darnton, John.

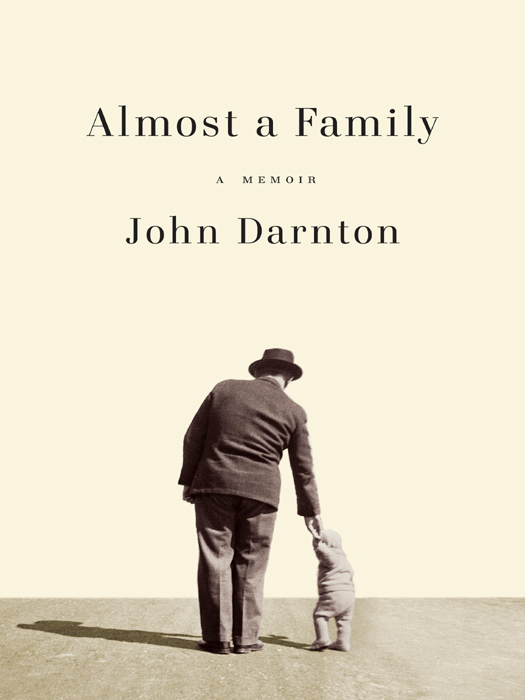

Almost a family : a memoir / by John Darnton.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-59524-9

1. Darnton, John. 2. Darnton, JohnFamily. 3. Authors, American20th centuryBiography. 4. Fathers and sonsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

PS3554.A727Z46 2010

813.54dc22

[B] 2010016835

Jacket photograph courtesy of the author

Jacket design by Carol Devine Carson

v3.1

For Nina

and

Kyra, Liza, and Jamie

and

Zachary and Ella Asher and Adara

A man who has spent his life in newspaper work is apt to believe that in the long run the best thing to do is to tell the truth.

B YRON D ARNTON

And over the hill the guns bang like a door

And planes repeat their mission in the heights.

The jungle outmaneuvers creeping war

And crawls within the circle of our sacred rites.

I long for our disheveled Sundays home,

Breakfast, the comics, news of latest crimes,

Talk without reference, and palindromes,

Sleep and the Philharmonic and the ponderous Times.

I long for lounging in the afternoons

Of clean intelligent warmth, my brothers mind,

Books and thin plates and flowers and shining spoons,

And your loves presence, snowy, beautiful, and kind.

K ARL S HAPIRO ,

Sunday: New Guinea

Contents

PROLOGUE

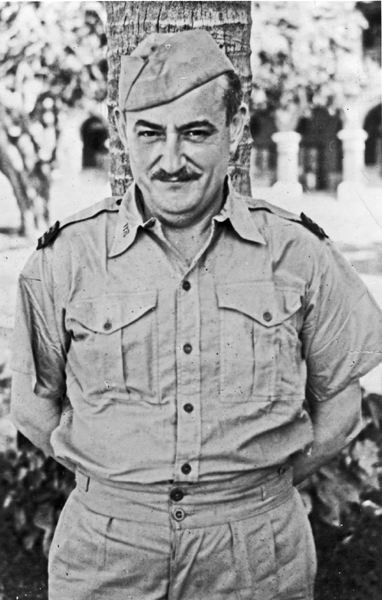

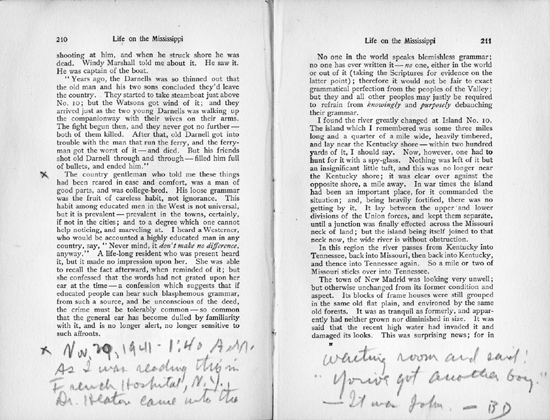

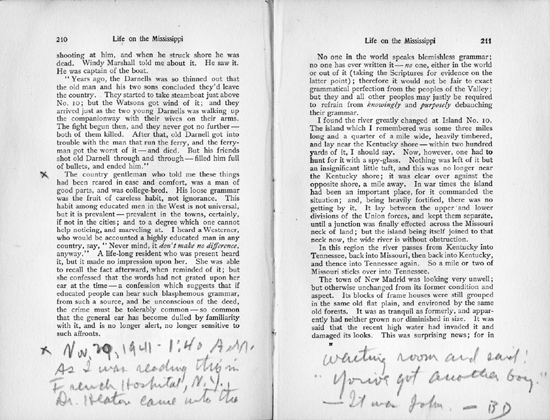

O ne of the few acknowledgments of my existence to come from my father happened in the middle of a feud between the Darnells and the Watsons on the banks of the Mississippi in the 1840s. That is, in the description of such a feud in Mark Twains Life on the Mississippi. There, halfway down page 210, just as friends of the ferryman shoot old Darnell through and throughfilled him full of bullets, and ended himlies an X in the margin. At the pages bottom, the X is explained:

Nov 20, 19411:40 AM. As I was reading this in French Hospital, N.Y., Dr. Heaton came into the waiting room and said: Youve got another boy.It was John.

B. D.

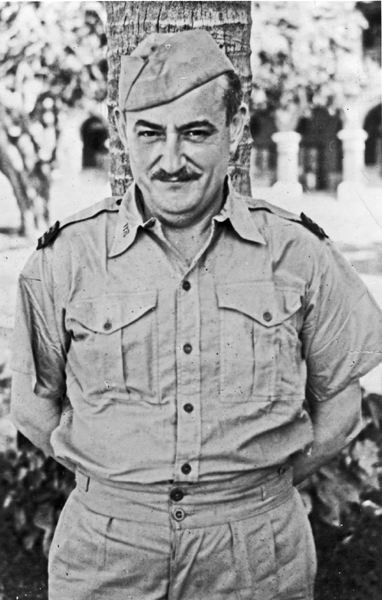

I like my fathers handwriting. Its in thick black pencil straight across the full width of both pages, sprawling and virile. The B. and the D.for Byron Darntonare full-bellied. No question about it: It is a declaration for history. Looking closely, I see the 20 after November is superimposed over a 19. A natural mistake: Its 1:40 a.m. Perhaps hes sleepy and thinks its still the night before. Or maybe hes so excited by the news that he wants to get it down and only a moment later, rereading, realizes his error. I picture the waiting room in my imagination. Its a stuffy enclosure off the entrance to the maternity ward: two windows, grime-covered, a lineup of straight-backed metal chairs, a beaten-down couch, framed prints of British foxhunting scenes on the wall, a rack with ragged copies of Colliers and The Saturday Evening Post, two stand-up ashtrays overflowing with cigarette butts, a radiator pumping away in the corner and worn linoleum on the flooror maybe a thin carpet. I see my father waiting there, reading. Hes sitting comfortably, self-contained, right foot resting on his left knee. His eyes sparkle with amusement at a nervous young man walking in and out from the corridor. Theyve exchanged a few friendly words. He provides the comfort of an older man, an old hand at this. A smile is ready to break out under his bushy dark mustache. Hes wearing a tweed jacket around his broad shoulders, and his dark brown trousers are beginning to lose the sharpness of their crease. His overcoat and fedora are hanging from a coatrack. Is he smoking? Surely. But what? Luckies? Camels? Is he carrying his fancy leather-bound flask, and does he offer the young man a swig of whiskey? He goes back to reading, back to the Mississippi. The door swings open and the doctor comes in to tell him about me. He stands up to take the news, beams, and pumps the doctors hand.

But what is he feeling? Had he wanted a girl? Is he worried about his wife? Does he feel the rush of second fatherhoodanother son to round out the family, another little body at the dining room table? Or is there just a smidgeon of uncertainty, regret even, the vague sensation of being trapped? Another mouth to feed on a reporters salary, another obligation. Now he will surely have to settle down.

He would be told to wait a few minutes before seeing his wife and baby. Does he, too, pace about now and look out the window at Eighth Avenue far below, yellow headlights penetrating what appears, perhaps, as a cold rain and billows of steam rising from the manholes? Or does he sit down again and jot the note in the margin and resume reading, lulled by the companionship of Twain, who goes on to describe the great flood of 1882, which broke down the levees, destroyed the crops, washed away the houses, and turned the mighty Mississippi into a scourge seventy miles wide?

The book resurfaced after forty-three years, hidden in plain sight in my brothers bookshelf. He sent it to me with a note: This isnt really a present, because by rights it belongs to you. Happy birthday! It had moved houses many times without being opened, testament to the immutability of a moment of supreme consequence (as far as Im concerned)and also to its transience.

And so I was born.

CHAPTER 1

F our days old, I was taken home to a cozy white clapboard house in the backwoods of Connecticut. According to family lore, I was carried across the threshold by a nurse, so that my brother, Bob, wouldnt become instantly jealous. My mother carried a toy for him, a brand-new fire engine. Butand here the lore surely verges into the apocryphalhe pushed it aside and demanded, Wheres my brudder?

Two weeks later, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor.

My father heard the news over the car radio as he drove our family off on a long-awaited vacation. He immediately spun the car around, dropped the three of us off, and headed to the headquarters of The New York Times on West Forty-third Street. The vast third-floor newsroom, on what was to have been a quiet Sunday afternoon, was thrown into high gear. Copyboys rushed from the agency tickers with the latest bulletins, and the switchboard was jammed with calls from a frantic public. Reporters and editors streamed in from all corners to man the phones and take up assignments. My father headed for an enclave in the city room, where eight wooden desks had been pushed together for an enterprise that had begun only six days earlier and that he headed: news broadcasts over the radio station WMCA (the forerunner to WQXR). Until well after midnight a steady stream of copy flowed out through a Teletype operator to the station, which beamed it to the city.