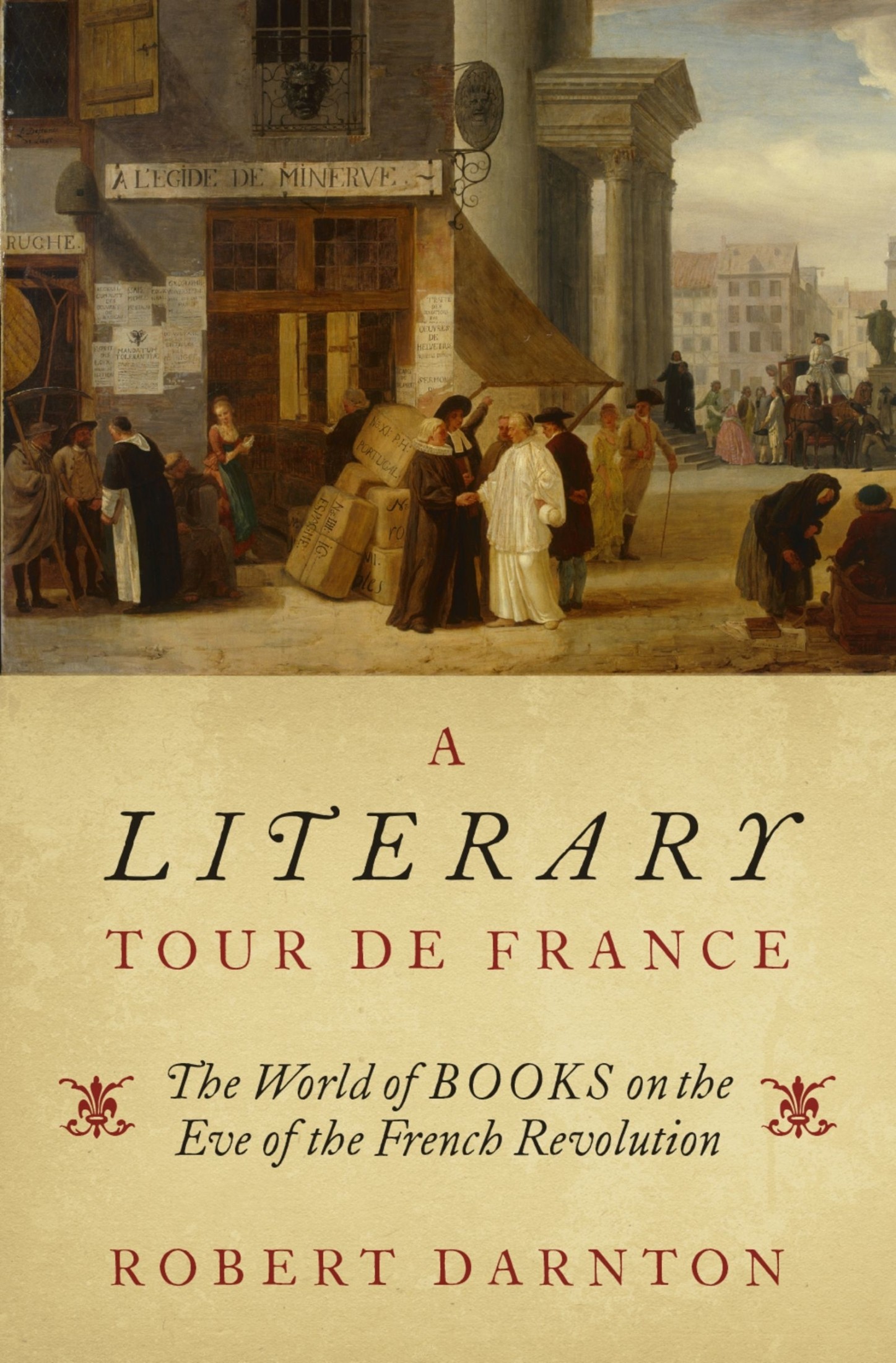

The world of books in pre-revolutionary france was endlessly varied and richrich, that is, in the variety of human beings who inhabited it. As an economic system it remained mired in the corporate structures that had developed in the seventeenth century: a guild of printers and booksellers that monopolized the trade in Paris; a pre-copyright legal system based on the principle of privilege; a royal administration to direct censorship and resolve internecine disputes; inspectors of the book trade charged with enforcing regulationssome three thousand edicts issued during the eighteenth century; and, outside the creaky, baroque institutions of the Bourbon state, a large population of professionals who supported themselves by getting books to readers.

Booksellers existed in all the major towns, and they came in all stripes and colors. A few patriarchs dominated the trade in each provincial center. Around them lesser figures built up businesses, cashing in on the expansion of demand from the mid-century years onward and struggling to survive in the tougher conditions of the 1770s and 1780s. On the outer edges of the legal system, a few dealers scraped together a living as best they could, usually by supplying the capillary system of the trade. In addition to these professionals, all sorts of individuals developed micro-book businesses. They included small shopkeepers who occupied a legal place on the market by purchasing certificates (brevets de libraire) from the royal administration; private entrepreneurs with no claim to legality; itinerant dealers who manned stalls on market days; binders who sold books on the sly; and peddlers of all varieties, some with a horse and wagon, others who hawked their wares on foot. These scrappy, ragged middlemen (and middlewomen; many of the toughest were wives and widows) functioned as crucial intermediaries in the dissemination of literature. Yet literary history has taken little notice of them. Aside from some rare exceptions, they have disappeared into the past. One purpose of this book is to bring them back to life.

Another is to discover what they sold. The question of what books reached readers and how readers read them opens up larger issues about the nature of communication and ideological ferment. I do not address those problems directly in this work, but I hope to provide a thorough account of how the literary market functioned and how literature penetrated French society on the eve of the Revolution.

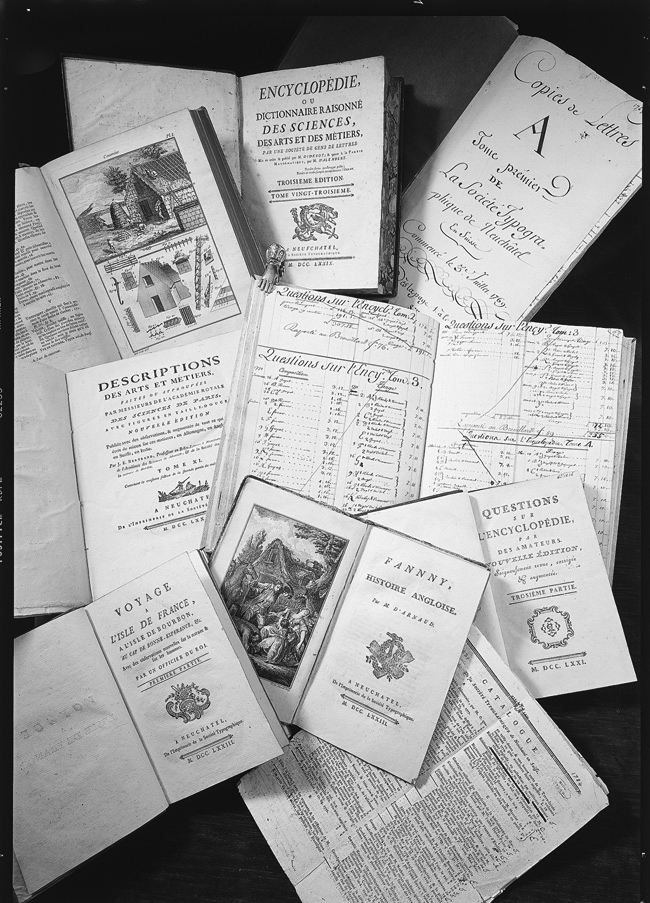

In order to do so, I intend to concentrate on the provincial dimension of the book trade. French history tends to be Paris-centric, yet less than 3 percent of Frances population lived in Paris during the eighteenth century, and the provincials consumed the great majority of books. They received some of their supplies from Paris, certainly, but more often they filled their shelves with works produced outside France; for as soon as a book began to sell in the capital, it was pirated by publishers who operated outside the kingdom. Piracy (the French usually called it contrefaon and also referred to contrefacteurs by saltier expressions such as pirates and corsairs) is a misleading term, although it was used liberally in the eighteenth century, because the foreign houses operated outside the range of the privileges (privilges) granted by the king of France. Within the kingdom, these privileges functioned as a primitive variety of copyright. Along with less formal authorizations known as tacit permissions (permissions tacites), they went only to books approved by a censor. The foreign publishers could reprint French books without concern for their privileges, and they could publish works that would never pass the censorship in France. Owing to economic conditions, especially the cost of paper, they also could turn out both kinds of books more economically than their French competitors. As a result, a fertile crescent of publishing houses grew up around Frances borders, extending from Amsterdam and Brussels through the Rhineland to Switzerland and down to Avignon, which then was papal territory. These publishers, dozens of them, produced almost all the works of the Enlightenment and, I would say, the greater part of the current literature (books in all fields, except professional manuals, breviaries, devotional tracts, and chapbooks) that circulated in France from 1750 to 1789. They conquered French markets by diffusing their works through an extensive distribution system, some of it underground, especially in border areas, where smuggling was a major industry, but most of it organized along the ordinary arteries of commerce, where the middlemen plied their trade, turning whatever profit they could get.