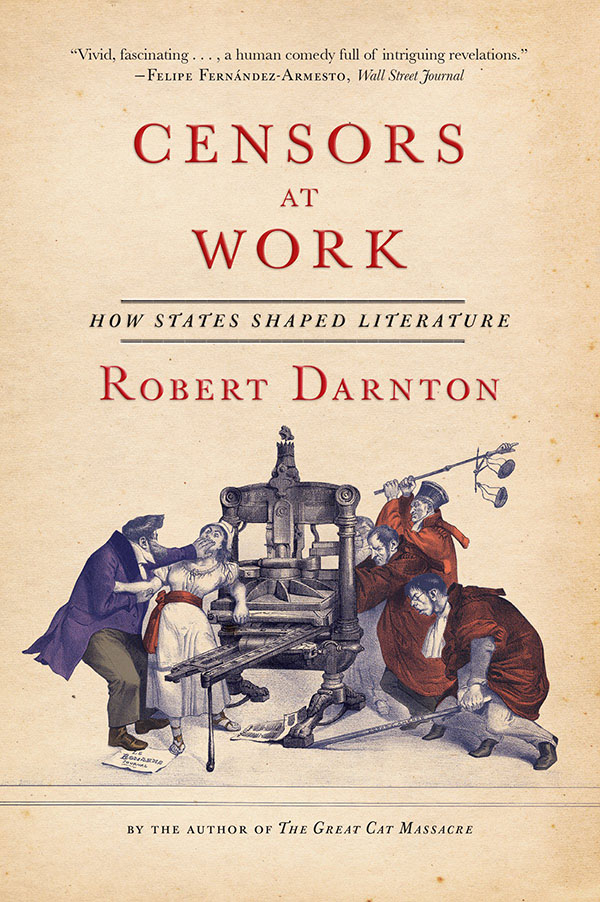

CENSORS

AT WORK

How States

Shaped Literature

ROBERT DARNTON

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

New York London

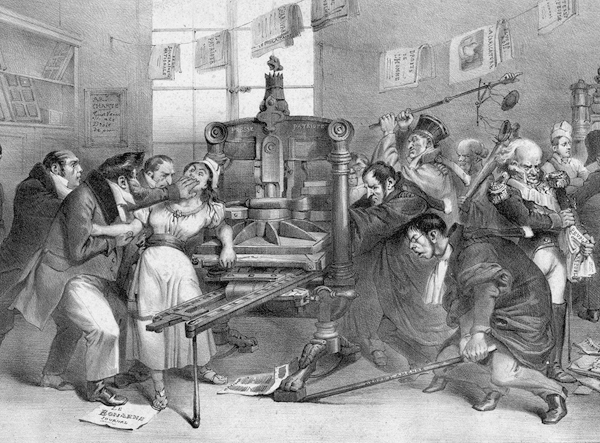

Frontispiece by J. J. Grandville and Auguste Desperret, Descente dans les ateliers de la libert de la presse. Paris, 1833. Lithograph. Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-13649.

Copyright 2014 by Robert Darnton

All rights reserved

First published as a Norton paperback 2015

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Helene Berinsky

Production manager: Louise Parasmo

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Darnton, Robert.

Censors at work : how states shaped literature / Robert Darnton. First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-393-24229-4

1. CensorshipFranceHistory18th century. 2. CensorshipIndiaHistory19th century. 3. CensorshipGermany (East)History20th century. 4. Literature and state. I. Title.

Z657.D26 2014

363'31dc23

2014010997

ISBN 978-0-393-24230-0 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-393-35180-4 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

This book is a much expanded version of the Panizzi Lectures, which I delivered at the British Library in January 2014 and dedicated to the memory of the first Panizzi lecturer, D. F. McKenzie. I would like to thank the Panizzi Foundation and my hosts at the British Library for their kind invitation. I also would like to express my gratitude to the librarians and staff at the Bibliothque de lArsenal and the Bibliothque nationale de France who have helped me track censors, authors, and police agents through their manuscript collections ever since the 1960s. The Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin provided me with a fellowship in 198990 and again in 199293. I shall always be grateful to the WiKo, its rector, Wolf Lepenies, and its staff. Solveig Nester helped me find my way through the labyrinthine complexities of the papers of the Central Committee of the Communist or Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands in East Berlin. And Graham Shaw offered expert guidance through the archives of the India Civil Service at the British Library in London. My thanks go to them; to Steven Forman, my excellent and sympathetic editor at W. W. Norton; and to Jean-Franois Sen, who improved my text while translating it into French for Editions Gallimard. The French edition includes a discussion of some theoretical issues, which was eliminated from the English edition. It can be consulted for the original French in quotations from manuscript sources, and the German edition contains the original German quotations. All translations into English are my own.

T he Manichaean view of censorship has special appeal when applied to the age of Enlightenment, for the Enlightenment is easily seen as a battle of light against darkness. It presented itself in that manner, and its champions derived other dichotomies from that basic contrast: reason against obscurantism, liberty against oppression, tolerance against bigotry. They saw parallel forces at work in the social and political realm: on one side, public opinion mobilized by the philosophes; on the other, the power of church and state. Of course, histories of the Enlightenment avoid such simplification. They expose contradictions and ambiguities, especially when they relate abstract ideas to institutions and events. But when they come to the subject of censorship, historical interpretations generally oppose the repressive activity of administrative officials to the attempts by writers to promote freedom of expression. France offers the most dramatic examples: the burning of books, the imprisonment of authors, and the outlawing of the most important works of literatureparticularly those of Voltaire and Rousseau and the Encyclopdie, whose publishing history epitomizes the struggle of knowledge to free itself from the fetters imposed by the state and the church.

There is much to be said for this line of interpretation, especially if it is seen from the perspective of classical liberalism or commitment to

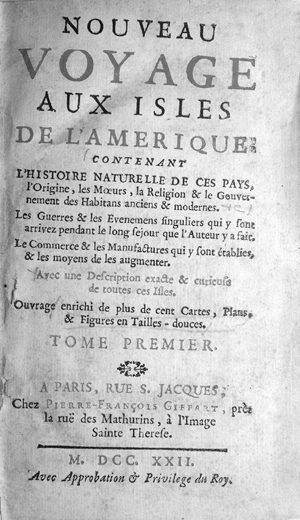

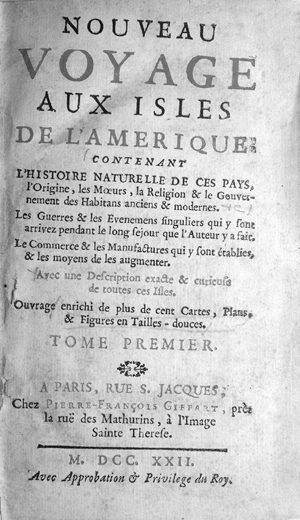

Consider, for example, the title page of an ordinary eighteenth-century book, Nouveau voyage aux isles de lAmrique (Paris, 1722). It goes on and on, more like a dust jacket than a title page of a modern book. In fact, its function was similar to that of dust-jacket copy: it summarized and advertised the contents of the book for anyone who might be interested in reading it. The missing element, at least for the modern reader, is equally striking: the name of the author. It simply does not appear. Not that the author tried to hide his identity: his name shows up in the front matter. But the person who really had to answer for the book, the man who carried the legal and financial responsibility for it, stands out prominently at the bottom of the page, along with his address: in Paris, the rue Saint Jacques, the shop of Pierre-Franois Giffart, near the rue des Mathurins, at the image of Saint Theresa. Giffart was a bookseller (libraire), and like many booksellers he functioned as a publisher (the modern term for publisher, diteur, had not yet come into common usage), buying manuscripts from authors, arranging for their printing, and selling the finished products from his shop. Since 1275, booksellers had been subjected to the authority of the university and therefore had to keep shop in the Latin Quarter. They especially congregated in the rue Saint Jacques, where their wrought-iron signs (hence at the image of Saint Theresa) swung through the air on hinges like the branches of a forest. The brotherhood of printers and booksellers, dedicated to Saint John the Evangelist, met in the church of the Mathurin Fathers in the rue des Mathurins near the Sorbonne, whose faculty of theology often pronounced on the orthodoxy of published texts. So this books address placed it at the heart of the official trade, and its super-legal status was clear in any case from the formula printed at the bottom: with approbation and privilege of the king.

A typical title page of a censored book, Nouveau voyage aux isles de lAmrique, 1722.

Here we encounter the phenomenon of censorship, because approbations were formal sanctions delivered by royal censors. In this case, there are four approbations, all printed at the beginning of the book and written by the censors who had approved the manuscript. One censor, a professor at the Sorbonne, remarked in his approbation, I had pleasure in reading it; it is full of fascinating things. Another, who was a professor of botany and medicine, stressed the books usefulness for travelers, merchants, and students of natural history; and he especially praised its style. A third censor, a theologian, simply attested that the book was a good read. He could not put it down, he said, because it inspired in the reader that sweet but avid curiosity that makes us want to continue further. Is this the language you would expect from a censor? To rephrase the question as the query that Erving Goffman reportedly set as the starting point for all sociological investigation: What is going on here?

Next page