Contents

Guide

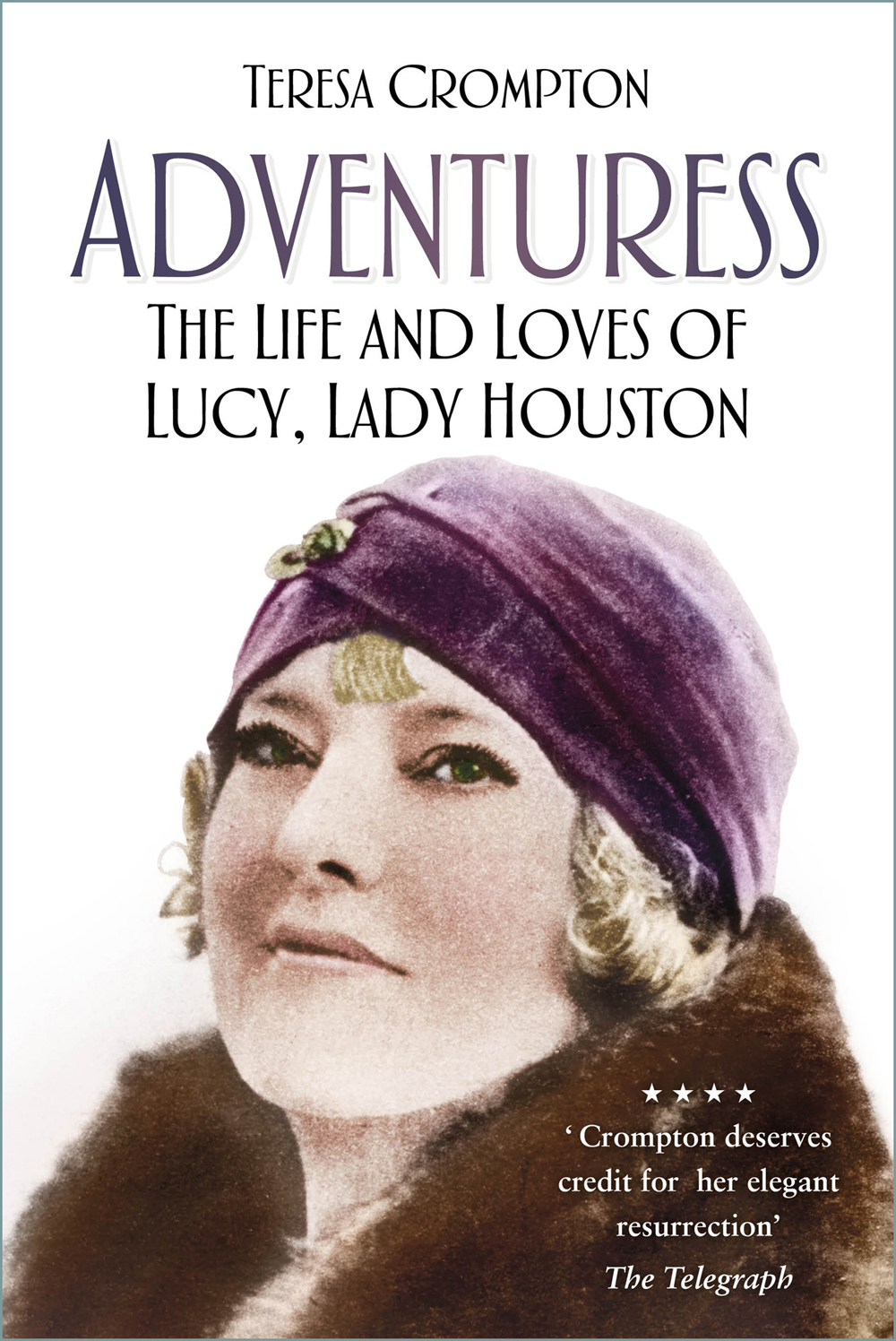

Adventuress: a woman adventurer, specif. one who seeks to become rich and socially accepted by exploiting her charms, by scheming, etc.

Collins English Dictionary

First published 2020

This paperback edition first published 2022

The History Press

97 St Georges Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Teresa Crompton, 2020, 2022

The right of Teresa Crompton to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75099 443 9

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Ancestry (website)

British Newspaper Archive (website)

Cambridge University Library (Stanley Baldwin and Lord Birkenhead correspondence)

Dr James P. Catty

Churchill Archives Centre, Churchill College, Cambridge (Churchill correspondence)

City of London School Archives

Cornell University, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections (Ford Madox Ford Collection, Violet Hunt Papers)

Dr. Peter Crompton

Hansard 18032005 Parliament UK (website)

John Rylands Library, University of Manchester (Ramsay MacDonald Papers)

Dr. Myrddin Lewis, Department of Humanities, Sheffield Hallam University

National Brewery Museum, Burton on Trent

Miranda Seymour

Alan Taylor, Folkestone and District Local History Society

University of Manchester Library (forged Russian letters correspondence)

University of Oxford, Bodleian Libraries, Weston Library, (T.E. Lawrence and Lord Wolmer correspondence)

NOTE ON SOURCES

Lucy Houston began her life in obscurity and ended it as a household name, with episodes of scandal, notoriety and public acclaim along the way; it is inevitable, therefore, that the biographers source material is varied. The richest mines of personal information are two biographies, written in 1947 and 1958 respectively by employees, newspapermen Warner Allen and James Wentworth Day. These are invaluable as a behind-the-scenes record of Lucys later lifestyle and her attempts to alter the course of British politics. The present work often draws upon them, and also gleans information from other first-hand accounts written by political associates such as Oswald Mosley and friends such as the writer Eveleigh Nash. Although in her later years Lucy was a prolific correspondent, not hesitating to publish letters of advice or commendation to strangers such as British Prime Ministers, Hitler and Mussolini, relatively few private letters have survived. A number of letters to and from Lucy are held in public archives, however. This biography has drawn upon, for example, her correspondence with Winston Churchill, T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia), Stanley Baldwin and the writer Violet Hunt. Much of the information revealed by the archival material for example, Lucys attempt to prevent Baldwin making Lord Birkenhead a cabinet minister, her dealings with Scotland Yard about forged letters from Ramsay MacDonald to leading Bolsheviks and her support of the novelist Violet Hunt has, to my knowledge, never been published before.

There is, however, less hard information about Lucys earlier life, in the late Victorian, Edwardian and First World War periods. Even when she did confide in others, as readers will soon note, her memory was highly selective, always impressionistic, sometimes deceitful and suspiciously self-serving. This book therefore uses other documentary sources to tell a fuller story of Lucys earlier life, and also some episodes of her later life unknown to those earlier biographers, such as her purchase of the forged Ramsay Macdonald letter to the Bolsheviks. The pages of the press, many local newspapers recently having been made available online, have also been helpful, particularly for establishing Lucys activities and whereabouts. To avoid drowning the text in source notes, rather than identify individual press articles, which were in any case often syndicated and thus appeared in many publications, I have generally referred to the press. Memoirs and biographies used are referred to in the text and details provided in a bibliography. Where archive material is used, referencing is provided in the endnotes.

Despite my best efforts to tell as complete a story as possible, gaps remain. Lucys childhood and her life as the teenage mistress of Frederick Gretton are largely undocumented and throughout there are periods, such as that of the Madame Chabault episode of 190608, where a biographer can only speculate how she was spending her time. Overall, big money leaves a bigger trail, and the task of accounting for Lucys whereabouts and activity is easier after her marriage to the millionaire Sir Robert Houston. This fact explains the biographys emphasis on the final decade of the subjects lifespan.

PREFACE

W ith a spring in his step Winston Churchill, Chancellor of the Exchequer, entered the Treasury building in Whitehall. It was 5.30 p.m. on the last Saturday in October 1929. The windows in the imposing faade of the deserted building were dark but Churchill had come for a secret meeting. Upstairs in his grand office he found Lord Hailsham (the Attorney General) flirting with the person he had come to meet, Lucy, Lady Houston. Her husband Sir Robert Houston, a multi-millionaire shipowner, had died and, having inherited the bulk of his fortune, Lady Houston was reputed to be Englands richest women. Strong-minded, imperious and formidable though she was, the thrice-married Lady Houston possessed both wit and charm.

Since Sir Robert Houstons death the Treasury had been trying to charge death duties on his estate and now his widow wanted the Treasury off her back. Lady Houston greatly admired Churchill and he had been surprised and delighted when she sent him a telegram offering to make a voluntary contribution to the nations coffers. The talks in his office continued for more than an hour over cups of tea. Churchill tried to persuade Lady Houston to hand over 2.5 million but the wealthy widow, as she would relate, argued and bargained and wheedled and bullied Churchill into accepting less. At 1.5 million the equivalent of 85 million today her offer was still an enormous sum. Churchill, Chancellor for five years, had been under continual criticism for his financial policies and he was delighted at this great personal triumph that would boost his reputation.

A few days later Lady Houston returned to pay the money over. She swept into Churchills office, he told a friend later, like a British Boadicea ridin in an invisible chariot, with unseen scythe-blades mowin down hordes of unguessed enemies! She sat down opposite him and took her cheque book from her capacious handbag. Flirting outrageously, she asked to borrow Churchills pen. Tell me, how many noughts are there in a million? she asked. Then she added archly, Dont you think youd better come and guide my hand? When the cheque was written Lady Houston handed it across the desk: Now, havent I been a good girl? Dont you think I deserve a kiss? When the news came out, Lady Houston boasted of her achievement in the press. Her donation, she said, was of enormous magnitude and importance. She had written the cheque with a joyful heart as an act of grace to the nation.