Copyright 2007, 2009 by Thomas Buergenthal

Foreword copyright 2009 by Elie Wiesel

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: April 2009

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

ISBN: 978-0-316-07099-7

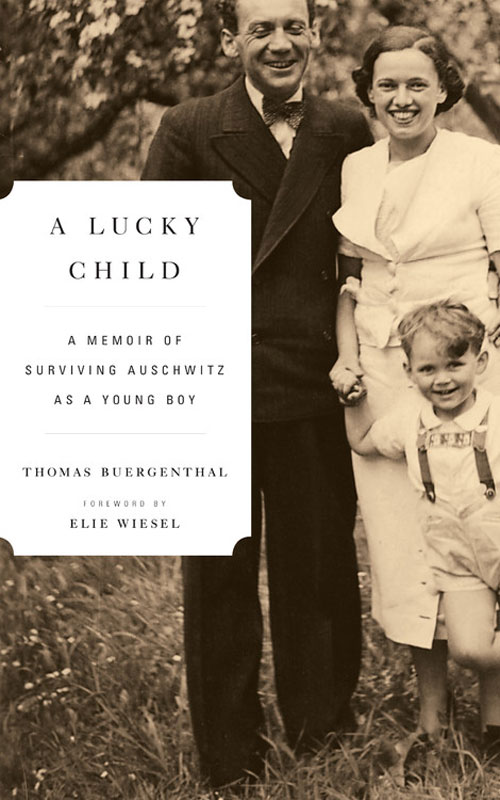

To the memory of my parents,

Mundek and Gerda Buergenthal,

whose love, strength of character,

and integrity inspired this book

ARE THERE RULES TO HELP A SURVIVOR DECIDE the best time to bear witness to history? Which is better: to dare to look directly into the blinding present, no matter how painful, or to await the detachment of hindsight which, being less painful, is more objective?

In the literature of what we so inadequately call the Holocaust, there were prisoners who, possessed by the fear of oblivion, defied every danger by becoming chroniclers. In the ghettos and in the death camps, and even in the shadow of the flames of Birkenau and Treblinka, men scrounged paper and pencil to write down and preserve their daily existence in all its appalling horror. These precious documents were discovered buried in the ground or under mountains of ash.

Following the war and shortly after their liberation from Auschwitz or Buchenwald, some survivors felt the need to speak out. The world had to be told the truth not only about their suffering but also about its own treachery. Others held their tongues, mostly because they did not have the strength to relive events that had been just about unbearable. And then too, let us be honest, people preferred not to hear what they had to say. It prevented them from clinging to their own certainties or, more simply, from eating well and sleeping in peace.

Thomas Buergenthal is among those who chose to wait. In his case, the long delay has been rich in human experience. He was already at the height of his career as a professor of law and as a judge before an international court when he decided to revisit his memories.

Is his testimony just one among many, similar to so many others? Well, yes and no. At first glance, all accounts seem to tell the same story. Sometimes we may even wonder whether it was the same German tormentor who abused, tortured, and killed the same Jew six million times. And yet, each story retains its own identity, its own voice.

The voice of the future world court judge strikes us by its need to seek out strains of humanity, even in the very depths of hell.

Kielce, Henrykw, Birkenau, Gliwice, and Sachsenhausen Buergenthal was among the youngest of prisoners in all these places of pain and damnation, where the power of evil and death seemed absolute. Being a mere ten years old in Birkenau made him a rarity, if not almost unique. How did he escape the brutality of the bosses, the agonies of hunger, the fatal diseases, and the selections? More simply put, how did he survive? If he believed in God, he might have evoked divine intervention, but he attributes his survival to luck. As a matter of fact, a clairvoyant had predicted as much to his mother: her son would be lucky. He remembers her saying so.

In the beginning there was the ghetto, with its famished wraiths, its nights of fear, its defeats; profession, wealth, and lineage counted for nothing there. Inside the primal nightmare, a most orderly chaos.

Then, deportation: the nocturnal passage into the unknown. Was it simply by chance that Thomas avoided the scrutiny of the infamous Doctor Mengele upon his arrival at Birkenau? Was there a tangible explanation for his luck? On another occasion, during a selection, the boy was bold enough to announce in German to a commandant that he could work. Amazingly, the commandant pulled him from the group already marked for death. Other boys his age had already gone to the other place, up there in the clouds, whereas he, Thomas, was still alive. One day, he was astonished to catch a glimpse of his mother in the womens camp.

How can those who have never been put to the test understand how human nature may bend under duress? Why does one man become a pitiless Kapo and victimize an old friend or even his own relative? What makes one man choose to exercise power through cruelty, while another from exactly the same background refuses to do so in the name of enfeebled and downtrodden humanity?

Thomas watches, learns, and remembers. Firing squads. Hangings. The prisoner who, not wishing to lose his dignity, kisses the hand of the unfortunate friend condemned to serve as his executioner.

In fact, even in the terrible camp at Sachsenhausen, Thomas finds friends older than he, men from his own district or from faraway places like Norway who help him.

Thomass stories from the days following liberation resemble earlier accounts in their thirst to understand what man, pushed to the very limits, is capable of.

As a child in Gttingen, Germany, he dreamed of going out onto the balcony with a machine gun in his hand to seek vengeance. Later, that dream shamed and humbled him. The same townsmen who, under Hitler, had turned their backs on their Jewish neighbors now embrace them. And Thomas, who has come to Gttingen to be with his mother, does not judge them collectively guilty.

Would he have written the same book fifty years ago? There is no knowing. But he has written it. That alone is what matters. And the reader must surely be thankful to him for it.

Elie Wiesel

THIS BOOK SHOULD PROBABLY HAVE BEEN WRITTEN MANY years ago when the events I describe were still fresh in my mind. But my other life intervened the life I have lived since I arrived in the United States in 1951, a life filled with educational, professional, and family responsibilities that left little time for the past. It may also be that, without realizing it, I needed the distance of more than half a century to record my earlier life, for it allowed me to look at my childhood experiences with greater detachment and without dwelling on many details that are not really central to the story I now consider important to tell. That story, after all, continues to have a lasting impact on the person I have become.

Of course, I always knew that someday I would tell my story. I had to tell it to my children and then to my grandchildren. I believe that they should know what it was like to be a child in the Holocaust and to have survived the concentration camps. My children had heard snippets of my story at the dinner table and at family gatherings, but it was never the whole story. It is, after all, not a story that lends itself to such occasional telling. But it is a story that must be told and passed on, particularly in a family that was, for all practical purposes, wiped out in the Holocaust. Only thus can the link between the past and the future be reestablished for our family. For example, I never really managed to tell my children, in the proper context, how my parents behaved during the war and the strength of character they displayed at a time when other people under similar circumstances lost their moral compass. The story of their courage and integrity enriches the history of our family, and it must not be allowed to be buried with me.