2021 Scott Cook. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

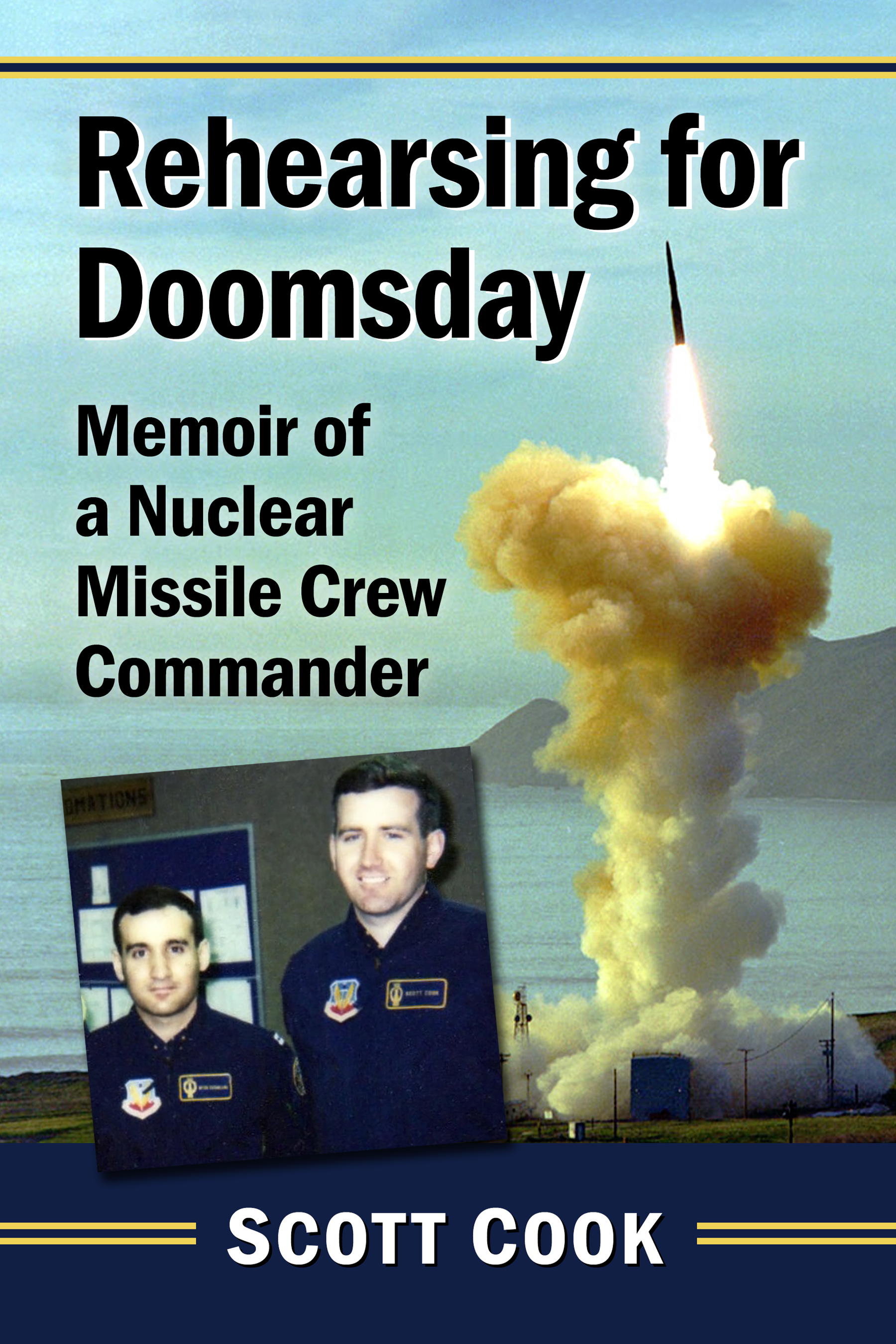

Front cover: New missileers at Grand Forks Air Force Base; On the left is Mitch Catanzaro, the authors roommate at officer training, the author is at right (courtesy Mitch Catanzaro); background: Minuteman launching from Vandenberg with mountains in background (Air Force photograph)

most importantly, taught me to love Gods Book.

Preface

This is a personal story, not an academic volume. It wasnt written as either a defense of, or repudiation of nuclear weapons. They exist. And, right or wrong, the United States government has made a series of decisions based on that reality.

This book is also not a critique of national policy, military strategy or a deep dive into the moral questions surrounding nuclear weapons. These are all important topics and I have my personal opinions. But Im no expert. There are library shelves full of other works which address those subjects much better than I ever could.

This is the story of a young boarding school physical education teacher who found himself on the front lines of nuclear deterrence. Thats the one topic about which I can proudly say, I am an expert.

I tried to relate my experiences in a way that was accessible to the average reader, who may not know a reentry vehicle from a recreational vehicle. Therefore, military jargon and technical descriptions, while not totally expunged, have been greatly minimized. For instance, you will not be subjected to endless pages describing the detailed inner workings of the Minuteman III missiles inertial guidance system. And for that you should give thanks.

The story of the U.S. Air Force missileer is an important one. After the nuclear scientists have created, the national policy makers have decided, and the president and generals have commanded, the ultimate burden to launch a nuclear weapon falls to a small group of junior officers, geographically isolated in two-person crews.

As you might imagine, missile duty was not a sought-after assignment by most. In my era, there were many more volun-told crew members than volunteers. Yet, once a military officer takes the oath of office, he or she is essentially agreeing to whatever Uncle Sam assigns them.

Of course, I cant discuss every aspect of my missileer experience. Much of those duties involved classified information, which for security reasons must still be protected.

Also, I have employed pseudonyms for almost everyone mentioned. The few exceptions are my family members, a couple of close friends and a few public figures. The other friends and colleagues arent public figures and may not want to be identified.

A word about North Dakota: I apologize up front for the jokes and less-than-flattering remarks about this great state. I have nothing personal against North Dakota or its people and I believe North Dakotans are some of the most hard-working, resilient and good-hearted folks in this country. If the missile fields were in rural Oklahoma or Iowa, those states would probably receive the same treatment.

But I was stationed in North Dakota and theres no getting around itthe Grand Forks area is a bleak, isolated and frigid stretch of land. Young officers, already stuck in an unwanted career field, channeled much of their frustration into complaining about their environment. That is common.

Grand Forks could be a lonely assignment because not many family members or friends ventured that far north to visit. Moreover, the local populace, although not unfriendly, could be somewhat stand-offish towards the military members living in their community. To be fair, maybe it was asking too much for North Dakotans to be enthused about the Air Force planting hundreds of nuclear missiles in their backyard.

I need to thank a few people. First, much gratitude goes to my parents and my brother, Todd, who read every word I wrote and gave me invaluable feedback. This book would not exist without their support, advice and encouragement. Thanks also to my beautiful wife, Beth, and our four children, Brett, Ben, Tori and Lindsay. I never cared much about where I was assigned as long as they were with me. They were and are my living, breathing therapy. And most of all, praise to God from whom all blessings flow. He has sustained me and walked beside me all these years.

Chapter 1

How Did I Get Here?

Full disclosure: There isnt any button. You dont launch a Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) tipped with a 150 kiloton nuclear warhead with the push of a button. You insert a key into a console and turn it. At least, thats how we were trained in 1989 when I was first assigned to missile crew duty. It was like starting a car, except with a million more horses under the hood. And no brakes. Once that beast goes, theres no stopping it.

Thankfully, I never had to turn keys for real. But my crew partner and I practiced World War III every month in the simulator on base. Then Id drive home and read a bedtime story to my kids. Not your typical job.

In our extensive Air Force training we learned that simply turning our keys wouldnt launch a bottle rocket, much less an ICBM. First, we needed to input the correct launch codes. Those codes were secured hundreds of miles away, their release authorized by only one man. The guy living at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C.

Yet even with the codes, two crew partners simultaneously turning keys equaled just one launch vote. You needed two votes to launch an ICBM. The other vote came from a second launch crew in another capsule. ICBM math is 4+2 = 1. Four crew members plus their two launch votes equal one launch.

So, despite what you might have read in a techno-thriller or seen in a movie, no one accidentally hits a button and launches a nuke. Nor is a deranged missile launch officer, or a group of them, able to deliberately launch an ICBM without authorization. There are too many safeguards, most of which are classified.

One of the few pleasant surprises during my crew duty in North Dakota was learning how secure nuclear launch systems really are. One of the many unpleasant surprises was learning how long North Dakota winters are. Spring, summer and fall were just weeks impersonating seasons. Great people up north. Rough environment.

When its minus 20 degrees outside and youre pulling the graveyard shift in a steel capsule buried 60 feet below the frozen tundra, you have ample time for personal reflection. Too much time. Depressing questions gnaw at your brain. Questions like How did I end up here? Or, Why didnt I talk to that Navy recruiter instead?