To prevent me from reading all day long my mother bought a piano.

A piano demonstrated that she had finally got back something of what had been lost by the war. A piano represented culture and achievement, and her youngest son was to be the embodiment of the return to grace. All the better that no one else on our working class street in Weston owned a piano.

Although I had no musical talent, I could use the piano as a form of retaliation upon my much older brothers.

I loved nothing on television so much as movies, especially the old ones and even the corny serials that had once been shown in cinemas before the war. Sunday afternoons were zones of freedom for all of us after church and before finally buckling down to do homework on Sunday nights. Serials and double-header movies played on TV in the afternoon but, sadly, so did Wide World of Sports.

My older, more powerful brothers would watch any sport at any time. I didnt begrudge them the baseball and football games on TV, and we all loved hockey, but they would watch anything, from water skiing to pole vaulting to motorcycle racing. I found it a crime that arcane sports, barely sports, trumped my movies. So I sought revenge.

Why are you playing the piano?

Im practising.

Why do you have to practise while were watching TV?

I have to practise whenever I can.

We cant hear the announcer.

To add pungency to my aggression, I played badly, repeating errors without ever correcting them. Playing badly took no extra effort. I did it naturally, to the acute pain of not only my brothers, but also my piano teacher, Mr. Rose.

After giving up on personally teaching me, Mr. Rose kept assigning me to new and different piano teachers in his school. One died, to be replaced by another who liked to mimic students playing by simultaneously playing on their forearms. After some alert parents had him fired, my next teacher was Frank, a hairy-fingered Italian who taught to make a few extra dollars to supplement his job playing for burlesques at the Blue Angel. Frank had seen it all, and the Tony Bennett knock-off let me bang away unchastised through clouds of his cigarette smoke. If I aggravated his hangover too much, hed tell me to run across the street to Inchs Drugstore to get him a cup of coffee.

My brothers used the same tactic. At least bring us some Kool-Aid.

Why should I?

Well give you a quarter.

When?

As soon as we have one.

I knew their weaknesses and they knew mine. A quarter would pay for a comic, a bottle of pop, and a small bag of chips. I brought them their Kool-Aids and lived in the dream of collecting the quarters, which were really nothing more than notional coins, bitcoins of the past, because they existed only as abstractions.

Older brothers were mixed blessings. They were frenemies avant le mot: champions, teachers, exploiters, torturers, benefactors, and the only ones who really understood you.

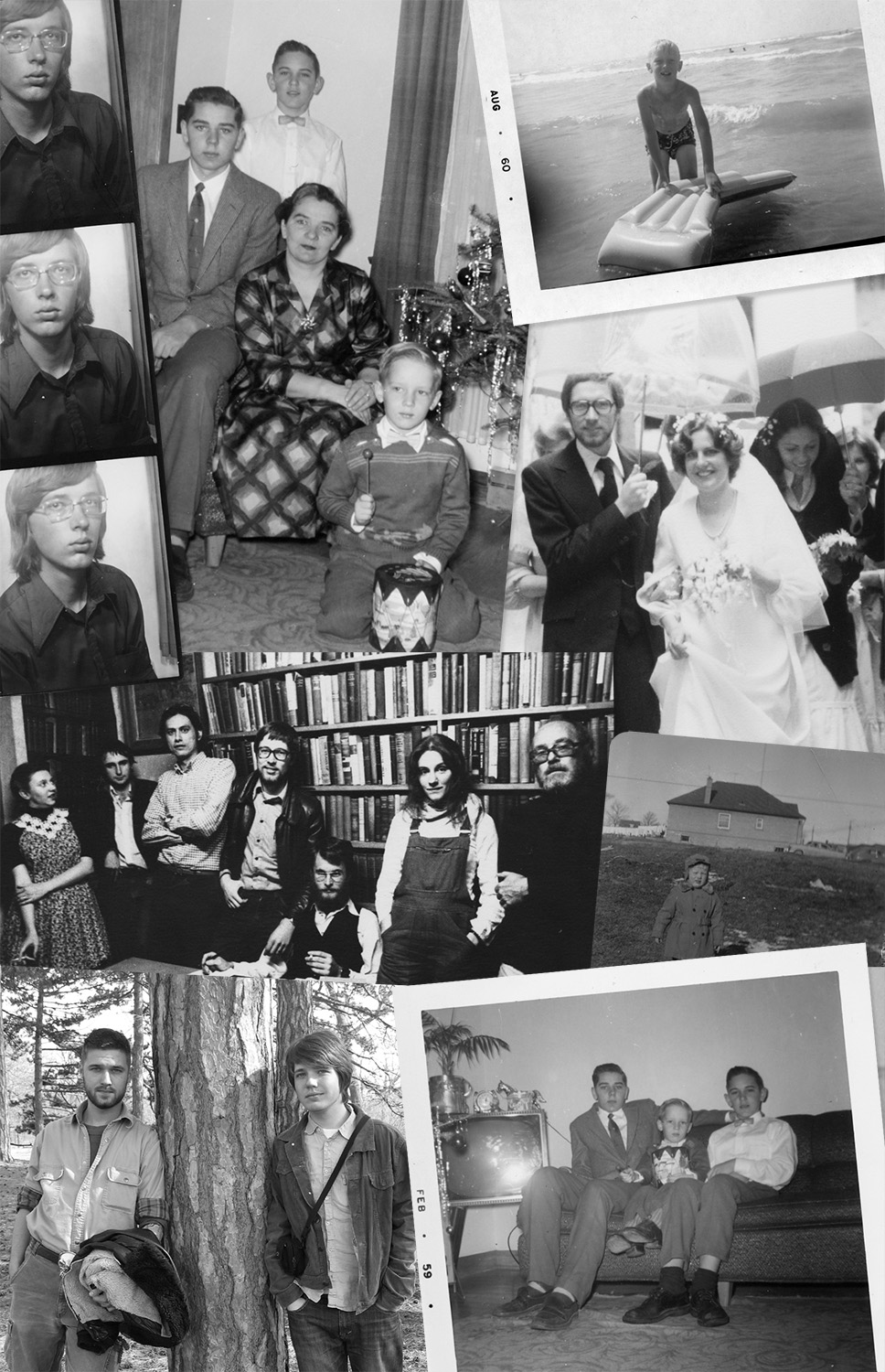

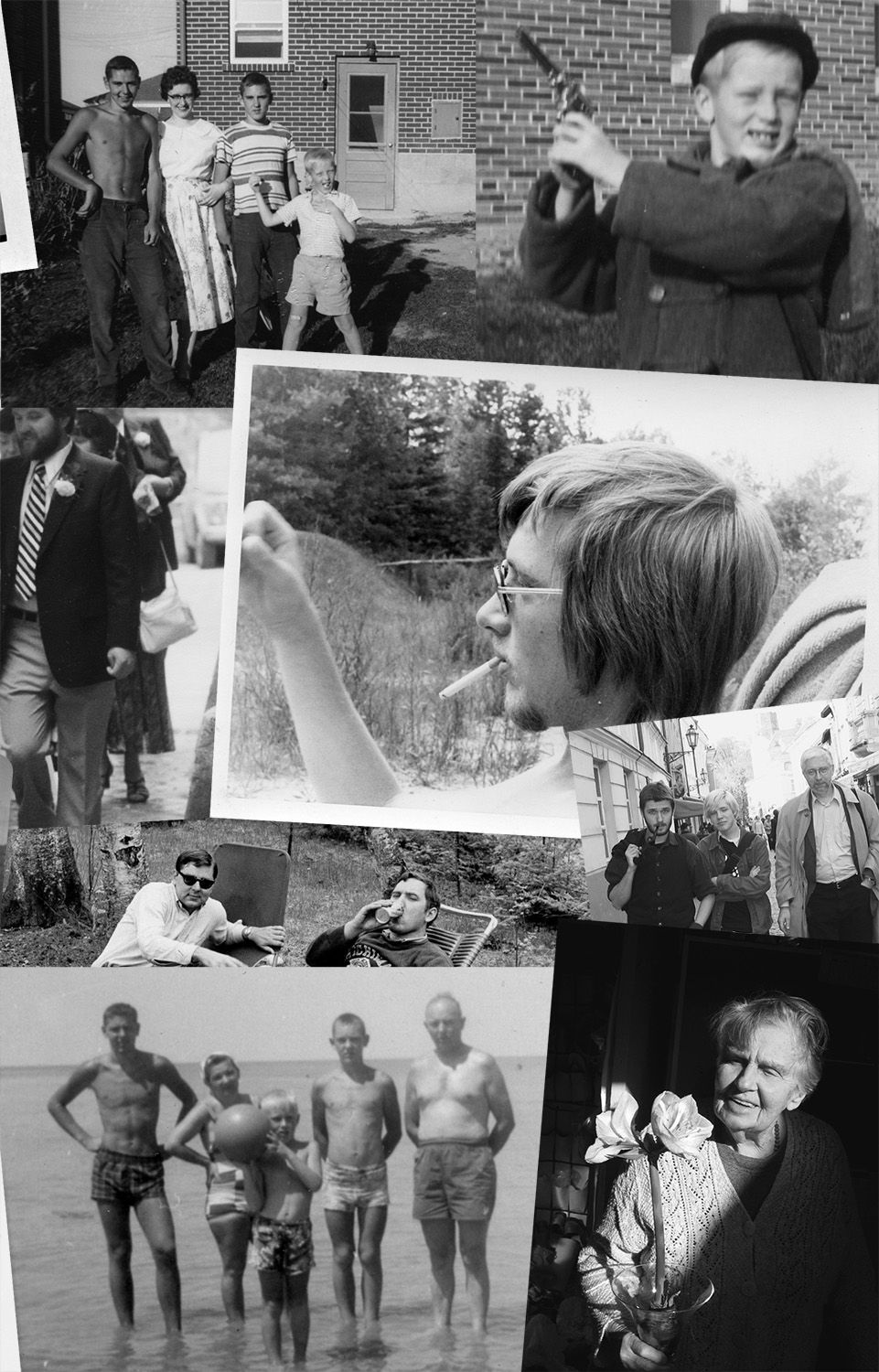

Andy and Joe were ten and six years older than me. Andy was practically an uncle, the one who dressed me in the morning when I was still too small to get my own socks on. They were strong, sporting boys. Joe was the only boy in the history of St. John the Evangelist elementary school who could knock a baseball right out of the playground. The two of them could play goalies on the driveway for hours with two hockey sticks and a tennis ball. They knocked a lightweight golf ball around nine holes in our suburban backyard and threw footballs out on the street with deadly accuracy.

Naturally, they expected to train me in their skills, but by a cruel roll of the genetic dice, I had come out timorous and inept, the third brother in fairy tales but without the happy ending. Their attempts at coaching could be hazardous.

Dont be afraid of the ball, said Andy.

Dont be afraid of the bat, said Joe.

I was backcatcher to my brothers, who were pitching and batting, and I stood well back of the bat, so far back that the ball was already arcing low, making it hard for me to catch.

I wanted to please them, so I did what I was told and pulled up close behind Joe. His bat caught me straight across the forehead on the back swing.

It could have been worse. I could have been hit on the forward swing.

~

Stand over there, said Andy. They had learned a little of my incompetence, and if they couldnt train me, at least they could keep me out of the way. I stood by the back door as the two finished preparations over by the garage. They had devised bolos by putting two hardballs into a pair of complicated string bags and then running a thin rope between them. Bolos were used to wrap around the feet of runaway cattle. We didnt have any cattle. Still, we might have cattle one day, and if we did and the cows ran off, we would have bolos to stop them in their retreat.

Andy swung the one ball around over his head while holding on to the second, and when he finally had enough momentum, he let go.

His aim must have been off.

I had never been hit by two baseballs in quick succession.

My footballs wobbled and never flew very far. Nor could I ever get the hang of catching one of them. I held my hands up, but the ball always flew between them. I was more goalposts than receiver.

Seeking to emulate my brothers, I played on the elementary school hockey team, and I was the only kid in grade four who was often asked not to bother to dress for the game. My enraged immigrant father would shout down at the coach from the stands, but the coach was indifferent. As for me, I was relieved. All skates seemed designed to hurt my ankles. In my four-year career on the ice, I scored only one goal, and it was disallowed by the referee, based on no rule I had ever heard of, unless it was to grant a career shutout to a hockey player who was not even a goalie.

This difference in temperament extended to other parts of our family life. Andy and Joe ate hamburgers, potato pancakes, and roast pork with gusto. I preferred sauted mushrooms and could only eat eggs if they were scrambled dry and served on lightly toasted bread that was quartered diagonally.

It drove them crazy to watch my mother prepare special meals for me, the baby who came into the family when my parents had finally reached middle-classdom after years as struggling immigrants. My brothers still remembered the bleak DP camp in Germany and the dreary farm outside Fort William in their early years in Canada.

They had helped my father build our house. At first, they all lived underground in the basement while the place was slowly banged together above them, scattering sawdust on them daily. As for me, I grew up in the completed house in my own bedroom with cowboy curtains and an electric train set. On warm days, I could open my window and listen to the real trains that passed through Weston a half mile away and imagine a better place than the one I inhabited, a place where sports were not the measure of a boys success.