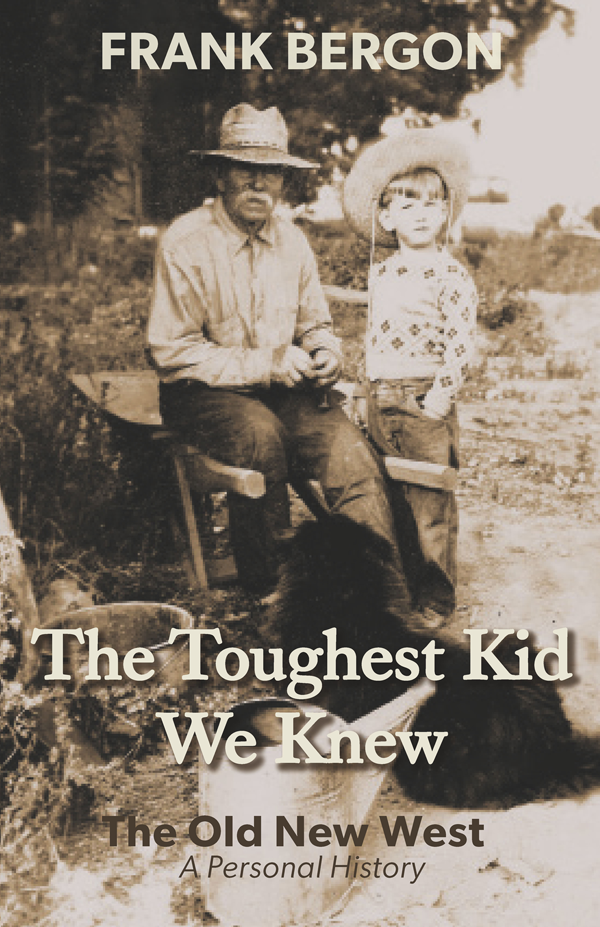

ALSO BY FRANK BERGON

Two-Buck Chuck & The Marlboro Man: The New Old West

Jesses Ghost

Wild Game

The Temptations of St. Ed & Brother S

The Journals of Lewis and Clark, editor

Shoshone Mike

A Sharp Lookout: Selected Nature Essays of John Burroughs, editor

The Wilderness Reader, editor

The Western Writings of Stephen Crane, editor

Looking Far West: The Search for the American West in History, Myth, and Literature, coeditor with Zeese Papanikolas

Stephen Cranes Artistry

University of Nevada Press | Reno, Nevada 89557 USA

www.unpress.nevada.edu

Copyright 2020 by Frank Bergon. All rights reserved.

Cover photo by Lina Bergon. Author portrait by Madeline Bergon.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Bergon, Frank, author.

Title: The toughest kid we knew : the old New West : a personal history / Frank Bergon.

Description: Reno : University of Nevada Press, [2020] | Summary: In a companion book to Two-Buck Chuck & The Marlboro Man, Frank Bergon presents a vivid personal history of the place where he grew up and the people of immigrant and migrant heritage he knew in the overlooked and most productive agricultural region of the United StatesCalifornias San Joaquin Valleythe New West of the twentieth century. If you want to understand how those from rural America think and feel today, you have to read this bookProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019054905 (print) | LCCN 2019054906 (ebook) | ISBN 9781948908641 (cloth) | ISBN 9781948908658 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Cultural pluralismCaliforniaSan Joaquin Valley. | San Joaquin Valley (Calif.)Social life and customs20th century. | San Joaquin Valley (Calif.)Social conditions20th century.

Classification: LCC F868.S173 B47 2020 (print) | LCC F868.S173 (ebook) | DDC 979.4/8053dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019054905

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019054906

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following editors for publishing portions or shorter versions of the following essays: to Bernardo Atxaga for My Basque Grandmother as Nire amama euskalduna in Erlea, to Darra Goldstein for Basque Family Style as Family Style in Gastronomica: The Journal of Food and Culture, and to Susan Shillinglaw for Reading Steinbeck in John Steinbeck: Centennial Reflections by American Writers.

Manufactured in the United States of America

FOR MY GRANDPARENTS

Prosper Bergon and Anna Costahaude

Esteban Mendive Aurtenechea and Petra Amoroto Egaa

AND FOR MY GREAT-GRANDPARENTS

Franois Bergon and Marie Jeanne Noussitou

Jean Costahaude and Franoise Bergez-Benebig

Juan Jos Mendive Bollar and Mara Carmen Aurtenechea Gorguena

Evaristo Amoroto Iruretagoiena and Manuela Egaa Eizaguirre

Introduction

One June night after a late dinner in Oakland, an old friend announced to a group of us, Your earliest memory will tell you the essential truth of your life.

We were incredulous. The essential truth of our lives? What did he mean?

He went on: Your first memoryor the earliest one you can recallwill reveal who you really are, or at least how you see yourself and experience the world. Lets try it.

We did. The narration of our earliest memories around the table expanded beyond a parlor game as we discovered past scenes or anecdotes that became to our astonishment more enlightening than expected. We were all friends. Wed known each other for years, meaning, of course, that we had a sharper sense of each other than of ourselves. No one hesitated in choosing an early memorywhether it was literal in every detail didnt matter. Each memory had the persuasive power of a story believed by the teller. As with all stories of emotional honesty, facts gave way to truths that surprised each of us when further illuminated by the commentary of others around the table.

Peoples memories that night conjured up varied early experiences: the sense of luck from finding a penny, the thrill of danger at seeing a black widow spider, the sensation of mystery flickering in the shadows above a childs crib, the feeling of safety while walking with parents under shady sycamores.

I found myself talking for the first time in public about a night when I was a boy in Los Angeles, a child fresh from Nevada,on a dark, sloping lawn of a relatives house. It was my earliest memory of California. I was alone, involved in some solitary fantastical adventure, when I heard the voices of two older boys at the edge of the lawn near the sidewalk. I barely discerned their figures in the dim light. Hey, look at this, one of the boys said. Hed picked up from the grass a wooden sword that my Basque uncle had carved for me in Nevada. It had a handle, hilt, and a curved blade painted yellowa pirates sword. I loved that sword. It was my favorite toy, all the more so because my favorite uncle had made it for me. Neat, the other boy said.

I felt panic. Thats mine, I yelled.

Then the boys ran. I ran after them, but being bigger and faster they soon disappeared into the night with the sword.

The aftermath fades into dimness. I have a vague sense of myself inside the house telling my parents and relatives what had happened. I mustve been crying, I mustve been consoled, although I cant remember. What I recall is a hazy adult response of general sympathy enlarged by an accepting view about how such things happen in life. What more firmly remains in my mind is the dark expanse of lawn sloping downwardan odd detail for L.A.into a deeper darkness where the thing I once cherished had now vanished.

At the Oakland dinner party, the expected Freudian interpretation of my story, initiated by one friend, was dismissed by the only professional therapist in the group, who was trained as a Jungian. The larger sense of loss described in this little story varied from person to person around the table. We all hate to lose or break things. We all have a sense of absence for the vanished lives we once lived, and every memory is tinged with its own death, an experience shared to varying degrees by those around the table that night.

When I think of my story about the sword, I recall from my childhood scrapbook a photograph of me in a piratescostume for a Halloween party in the high desert town of Battle Mountain, Nevada. My mother took the photo. I dont remember the moment, but there I am next to my bare-bellied cousin in her veil and gauzy harem pants. A pirates bandana covers my head. Im wearing a blousy shirt and billowy pants. Sticking through the wide sash around my waist is the pirates sword my uncle had carved for me. I havent looked at the photo for years, but I remember it, and I wonder if without my memory of the photo I wouldve remembered that precious sword and its later loss in the way I have. Our memories, psychologists tell us, are reprints of earlier memories, like photos of photos, one layered on top of the other. What we end up remembering are memories of memories in constant flux.

For years I resisted dredging up early memories of my youth for fear of resurrecting painful experiences or hardening them into false stories. I make this admission of evasion with some regret. Because I didnt want my memories rigidified or shaped too quickly by negative feelings, I may have abandoned much of the past. Now that Ive written the story of that night in California when the sword was stolen, I realize I was recounting the story as Id narrated it to my friends in Oaklandwith a few added recollections. What Ill now continue to remember, I know, is not the night as it happenedthats lostbut as its dramatized in the words of the story Ive written.