Title: Two-buck Chuck & the Marlboro Man : the new Old West / Frank Bergon.

Description: Reno ; Las Vegas : University of Nevada Press, [2019] | Identifiers: LCCN 2018039126 (print) | LCCN 2018041047 (ebook) | ISBN 9781948908054 (ebook) | ISBN 9781948908061 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Central Valley (Calif. : Valley)--Social life and customs--21st century. | Central Valley (Calif. : Valley)--Social conditions--21st century. | Cultural pluralism--California--Central Valley.

Introduction

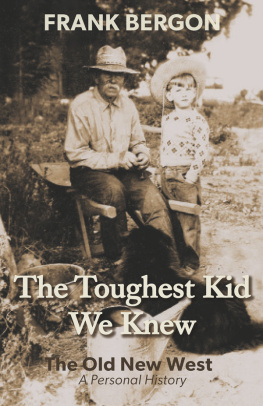

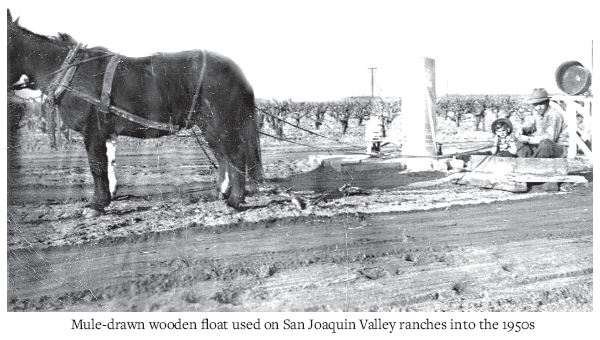

To think about the American West in the twenty-first century astonishes me when I look at an old black-and-white photograph taken on my familys California ranch when I was five. Im wearing a straw hat and sitting in a wooden float used to compact and smooth vineyard rows for raisin drying. Next to me, a ranch worker from Oklahoma in a small-brimmed Stetson fedora holds the reins to a mule dragging the scraper and us through a vineyard.

Now in the twenty-first century, mechanical harvesters roar through the night from dusk to dawn picking wine grapes in similar vineyards. Against the racket of this mechanized harvest, the remnant of the Old West in the photo glows as if from a distant galaxy. Less distant is how the Dust Bowl migrant behind the harnessed mule and todays Mexican immigrant on a night harvester might think and feel, sharing Old West beliefs in the power of individual resilience and the future rewards of hard work. In the rural West, core beliefs change more slowly than the surface of peoples lives.

This book is a personal portrayal of how Californias Great Central Valley breaks down distinctions between the Old and New West to create Americas True West, a country where the culture of a vanishing West lives on in many contemporary Westerners, despite the radical technological transformationsaround them. I write about rural and small-town Westerners, some with ties to Nevada, Oregon, Idaho, New Mexico, Arizona, Wyoming, Oklahoma, and Texas, whose lives have intertwined with mine, all shaped, as I was, by Californias Great Valley, a place itself shaped in large part by migrants and immigrants. Many I write about see themselves as part of a region and way of life most Americans arent aware of or dont understand. In their myriad voices I hear a vibrant oral history of todays rural West.

I was born in Nevada, lived in the Rockies, taught in the Pacific Northwest, and came of age in the San Joaquin Valley, where I grew up on a Madera County ranch as a Californian and an American Westerner. I didnt always understand these connections. One morning as a kid I was riding with my dad in his pickup down a country road when he waved to a lone driver approaching in a black truck.

Whos that? I asked.

I dont know.

Whyd you wave to him?

Thats when my father explained the significance of his greeting, not so much a conventional wave, really, as a flick of the fingers upwardthe heel of his hand still rested on the steering wheelin half-acknowledgment, half-blessing. Thats the hospitality of the West.

We were in the center of the San Joaquin Valley. It and the Sacramento Valley form Californias Great Valley, 450 miles long constituting nearly three-fifths the length of the state, an area larger than Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Massachusetts combined, a massive country of farms and ranches, andas I was toldthe richest, most productive agricultural region in world history.

Nevertheless, a few months earlier, after moving from Nevada, Id asked my dad when we were going back to California.

We are in California, my father said.

Id thought California was Los Angeles, where wed lived briefly before moving to the center of the state.

Once I got my geography straight, I had no doubt that California was the West and I was a Westerner. I lived on a ranch. It had horses, mules, sheep, and cattle. It also had cotton, grapes, and alfalfa, but nobody said farm in those days. Everything was a ranch, as in cotton ranch or dairy ranch. My grandfather and dad were ranchers, even after the cattle business went bust and they farmed the dirt.

To put a twist on what my old teacher Wallace Stegner told us at Stanford, rural California is like the rest of the West, only more so. As a region, the San Joaquin Valley in its extreme otherness from the states tourist and metropolitan haunts has caused native-son writers like Gerald Haslam and David Mas Masumoto to distinguish this rural country as The Other California. Its this other California that best illuminates what playwright Sam Shepard dramatizes in True West, a play set in a rural California ranch house next to an orange grove, forty minutes east of Hollywood at the intersection of a sprawling suburb and a desert of yapping coyotes. Shepard as a boy lived on a ranch in nearby Duarte, raising sheep and avocados, and he later worked as a ranch hand and a lay-up stable boy near Chino. The California I knew, old rancho California, is gone, he once explained. It doesnt exist, except maybe in little pockets. I lived on the edge of the Mojave Desert, an area that used to be farm country.

This interpenetration of a vanishing Old West and an emerging New West creates the True West, as it always has, dramatized in the aspirations and disappointments of two brothers in Shepards play. There was a life here then, says one brother with regret about the disappearing ranch country. The other responds with dismissive toughness, Theres no point in cryin about that now. Whats true about theirWest emerges as paradoxical. A mythical Wild West still exists in their minds, somewhere out in the desert, only to become a violent, immediate reality when the brothers end up viciously fighting each other. An equally mythical West manifests itself at the dawn of a new day as one brother exclaims with a Western whoop of can-do optimism, It makes me feel like anything is possible. Ya know? The other brother seeks fulfillment of his True West desires, but elsewhere, farther West, as it were, in the San Joaquin Valley, where embodied in his memory lives a beautiful green-eyed woman he desperately tries to phone but hangs up in True West disappointment because he cant remember whether she lives in Fresno or Bakersfield. He only knows shes somewhere in the truer West of the San Joaquin Valley.