The Muses

| 1 POETRY | Calliope |

| 2 HISTORY | Clio |

| 3 MUSIC | Euterpe |

| 4 DANCE | Terpsichore |

| 5 LOVE POETRY | Erato |

| 6 TRAGEDY | Melpomene |

| 7 COMEDY | Thalia |

| 8 GEOMETRY | Polyhymnia |

| 9 ASTRONOMY | Urania |

And, in the words of Brillat-Savarin,

Gasterea

is the tenth muse.

She presides over all the pleasures of taste.

Contents

1

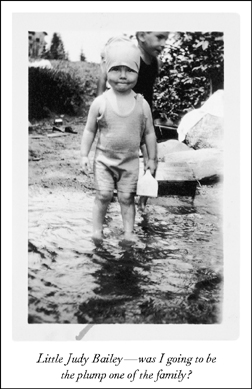

Growing Up

When my mother was well into her nineties, she announced that she had an important question for me and wanted an honest answer. I steeled myself for something weighty, perhaps about whether I believed in heaven and hell.

Then she looked at me and asked: Tell me, Judith, do you really like garlic? I couldnt lie. Yes, I admitted, I adored garlic. She looked so crestfallen at that moment that I was sure she felt a sense of finality about the wayward path her younger daughter had taken.

To her, garlic represented everything alien and vulgar. It smelled bad, and people who handled it or ate it smelled bad. Moreover, it covered up the natural flavor of honest foodand that was suspect. Those French chefs, for instance, why did they have to put a sauce on everything, anyway? No doubt to disguise the taste because what was underneath wasnt very fresh to begin with.

In my mothers house we were always being told to get rid of the smells, to make sure that the kitchen door was shut, that the windows were open. Not only was garlic banned, onions were permitted only when a lamb stew was being prepared, for which two or three well-boiled small white onions per person were deemed appropriate. Thats all that were purchased; Mother didnt want our cook, Edie Price, sneaking a little chopped onion into her meatloaf. And heaven forbid that indigestible, raw pieces might find their way into a tuna-fish sandwich.

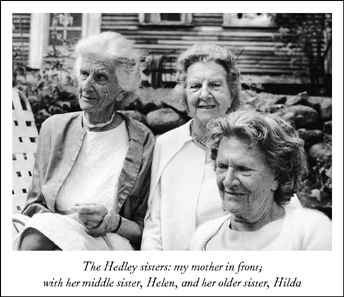

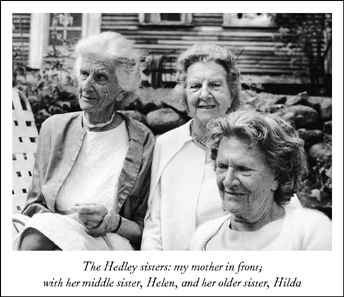

Still, I have to admit that the unadulterated English-style food I grew up on had its merits. I always loved our Sunday dinner prime rib roast with Yorkshire pudding, which my British grandfather, whenever he was present, would carve at the table, deftly cutting thintoo thin, I always thoughtrosy slices. My father, Charles Bailey, who was called Monty because he grew up in Montpelier, Vermont, somehow never lost the mischievous charm of a small-town boy after he had to settle in New York City. When he married into the Hedley family, he made a point of carving clumsy, thick slices, and so was banished as the family carver. My mother took over. I can still see her standing at the head of the table honing her knife on a sharpening steel, and I would always try to sneak a nibble from the platter when she wasnt looking. The knuckle-bone meat on a lamb roast was irresistible.

I am grateful, too, that those organ meats that people spurn today often graced our table: liver and bacon, beefsteak and kidney pie, breaded sweetbreadsI lapped them up and still find all forms of innards an earthy delight. Frugality was considered a virtue. One never let things go to waste, so Edie learned to turn leftovers into wonderful dishes: crispy croquettes with creamy lamb, ham, or chicken inside; shepherds pie of ground-up leftover lamb with a mashed-potato topping; minced meats in cream on toast; stuffed vegetables. We also had a meatless night once a week, either for the sake of economy or because it was good for us to forgo the pleasure of flesh, Im not sure. For quite a few years after I graduated from the nursery table to the grown-up dinner table, I thought when we were served breaded and fried eggplant or broiled mushrooms that they were a form of meat. Of course, I didnt dare ask, because one wasnt supposed to talk about food at the table (it was considered crude, like talking about sex). And if we indulged in appreciative sounds like yum-yum, we just might be sent from the table.

Nor could we make disparaging remarks if something displeased us. I remember how endlessly long the winter seemed when all that Mr. Volpe, our Italian fruit-and-vegetable vendor on the corner, could produce was overgrown root vegetables, sprouts and cabbage, and tired potatoes. Then what greens we could get were cooked so long that an unappetizing cabbagy smell permeated the air, and it was hard to get down our due portion. But we werent allowed to say a word. It did take me some time, though, to appreciate parsnips and broccoli. When, finally, spring broke through and we tasted our first asparagus, even though slightly overcooked, it was a treat worth waiting for. And we were allowed to pick up the spears with our fingers.

But I dont remember ever going shopping with my mother in the city to pick out the first vegetables and fruits of the season. Food shopping was invariably done by phone, as though to keep a distance from the things of the earth. In the summer, though, a truck with fresh farm produce would do a tour of the lake in Vermont where we had our summer cottage, and it was fun to go out and greet the local farmer and get a look at what he had just pulled from the soil. Every week the butchers truck would stop by, and I once persuaded him to let me ride with him as he made his rounds. I was impressed with the way he wielded his knife and would lop off a slab of meat which, when he put it on the scales, would always come within an ounce of what the customer had ordered. The back of the truck was chilled only by a block of ice, and as the warmth of the summer day penetrated, the smell of raw meat became tantalizingly strong.

Meat was such an important part of everyones diet that when we were plunged into World War II and were suddenly confronted with rationing, there was a sense of deprivation. I was away at college in Bennington, Vermont, in those years, and we had a huge Victory Garden in which all had to participate. I remember how the erudite critic Kenneth Burke insisted that he conduct his class out in the burgeoning fields, because he felt that having our feet planted firmly in the soil and nurturing the fruits of the earth would encourage our minds to soar. We were also asked to volunteer for poultry duty, and I felt very virtuous beheading and plucking and eviscerating chickens by the dozensall in expectation of a good dinner, of course. Bennington was known for its superior food, and Im not ashamed to admit that, after sampling the fare at a number of sister colleges, I just may have chosen Bennington because I liked to eat well.