Acknowledgments

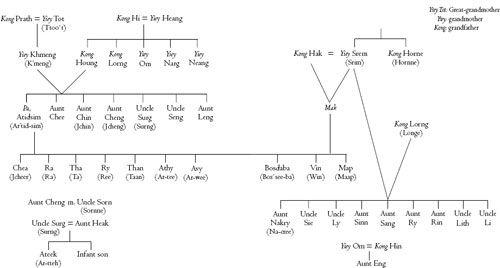

I remember a little girls wish for the world to learn the bitter chill of her grief, and of the tragic death of her family. Her wish is mine and it is realized. I must thank those individuals whove helped the dream come true: Ryan Hinke, my dear, loving friend, who provides a home with precious solitude that allowed me to write this memoir.

I am grateful to Uncle Seng for bringing us to America.

I am indebted to Amy Cherry, a sensitive, shrewd, godsent editor.

Meredith Bernstein, my agent, I thank you for believing in my story. Your kind words gave me courage.

My sister Channary, who cheers me on in my journey.

I thank the Literary Arts, Inc., and those who have helped Cambodia and her people in the Khmer diaspora.

PREFACE

A Seed of Survival

To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven.

E CCLESIASTES 3:1

I wake, confused. Its still dark . My past has haunted me again. Memory has taken me back in my dreams, a hapless passenger, even though Im no longer in Cambodia. In my nightmares I am trying to keep a childhood promise that I made to the spirit of my mother, who came to me in my sleep twenty years ago. A promise made in another dream which I must honor.

In this dream, I am crying out to God to help me find Map, my three-year-old brother. Enemies are infiltrating the United States. I hear a voice cry out. I cant distinguish words, only human fear. America is being invaded? This cant be happening . I fled to America to escape war. Now where do I go? My questions are shattered by the familiar sound of gunfire, a hollow boom, the distant chatter of artillery that still sends terror pulsing through my veins. The sounds are of Cambodia, but the landscape is of the Pacific Northwest. The guns speak from somewhere I cant see, beyond a grove of pine trees in the shadow of a mountain. The world has become a landscape of light and shadow. Around me, a human river flows crazily out of control. People are running everywhere. A sobbing woman carries a bundle of clothes and a child, slowed by the weight of her own terror. I am stiff in fear and shock. In the blur of faces around me, there are no Americans, only Cambodians.

I am carried along by the crowd, and yet Im alone, without my family. Where is Map, my baby brother? My heart races and my head moves like a windshield wiper, looking for him. I cant find him. The sound of gunfire obliterates the human noise around me. Its getting closer and louder. My sobs accelerate, and I begin to gasp for air. My lungs are screaming, my insides crying out in unison with my mind. I can no longer run and drop to the ground. I scream with all my might: No, my promise! I cant lose another brother! God, help me.

It has been twelve years since I came to America. From here, I look back upon a childhood consumed by war. I could recognize the sounds of war at the age of four, when the spillover from the Vietnam conflict forced my family from the home my parents had spent their life savings to build in the affluent Takeo province in southern Cambodia. By the age of ten, I was forced to work in child labor camps, among thousands of children separated from parents and siblings by a system of social slavery instituted by the Khmer Rouge in their bizarre quest to create a utopian society.

Family ties were suddenly a thing of suspicion. Control was everything. Social ties, even casual conversations, were a threat. Angka , the organization, suddenly became your mother, your father, your God. But Angka was a tyrannical master. To question anythingwhom you could greet, whom you could marry, what words you could use to address relatives, what work you didmeant that you were an enemy to your new parent. That was Angka s rule. To disobey meant the kang prawattasas , the wheel of history, would run over you. Thats what they told us as we cast our eyes downward under the weight of their threats.

Unlike so many of the children I worked with in muddy rice fields and irrigation canals, unlike many in my own family, I outran the wheel of history. I survived starvation, disease, forced labor, and refugee camps. I survived a world of violence and despair.

I survived.

Since 1981 my new home has been mostly in Oregon, as verdant as the land I left, but different. The coconut and papaya groves, the mango trees that grew in front of my childhood home, have been replaced by mountains dense with pine and fir, timber-flanked valleys, and cold, clear streams. From dramatic coastal cliffs to lacy spigots of waterfalls that feed the Columbia River Gorge, the sites, scenes, and sounds of this place have become my image of America. Now, strangely, it has also become the landscape of my nightmares.

In Cambodia the term for childbirth is chhlong tonl . Literally translated, it means to cross a large river, to weather the storm. Looking back, I have crossed the river on my own, without my mother. I have started a new life in a new country. I have learned a new language and lived in a new culture. I have been reincarnated with a new body, but with an old soul. It lives symbiotically inside me.

In many ways I occupy a world of blurred boundaries. Since the fall of 1989, I have been involved as a researcher on the Khmer Adolescent Project, a federally funded study of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among 240 Cambodian youths who endured four years of war in Cambodia.