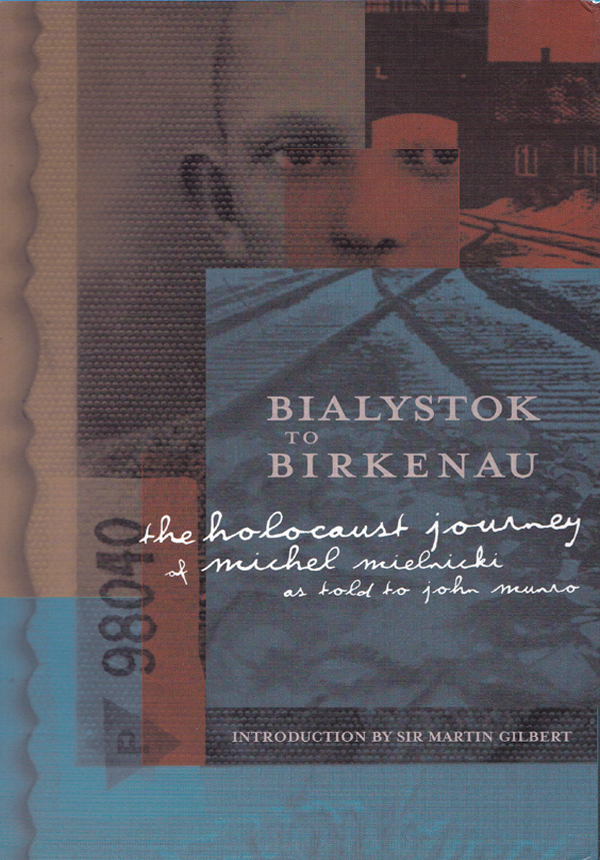

BIALYSTOK

TO

BIRKENAU

The Holocaust Journey of Michel Mielnicki

as told to

JOHN MUNRO

Introduction by

SIR MARTIN GILBERT

RONSDALE PRESS & VANCOUVER HOLOCAUST EDUCATION CENTRE

BIALYSTOK TO BIRKENAU

2000 Michel Mielnicki and John Munro

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher, or, in Canada, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic method, a licence from CANCOPY (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency).

RONSDALE PRESS

3350 West 21st Avenue

Vancouver, B.C. Canada

V6S 1G7

Set in Garamond: 12pt on 14.5

Typesetting and Cover Design: Metaform, Vancouver, B.C.

Printing: Hignell Printing, Winnipeg, Manitoba

Ronsdale Press wishes to thank the following for their support of its publishing program: the Canada Council for the Arts, the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the British Columbia Arts Council, and the Province of British Columbia through the British Columbia Book Publishing Tax Credit Program.

CANADIAN CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Mielnicki, Michel, 1927

Bialystok to Birkenau

Includes index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-0-921870-77-7 (print)

ISBN 978-1-55380-306-5 (ebook) / ISBN 978-1-55380-305-8 (pdf)

1. Mielnicki, Michel, 1927- 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939-1945) Personal narratives.

3. Holocaust survivors Canada Biography. I. Munro, John A., 1938-II. Title.

D804.196.M55 2000 940.5218092 C00-910585-9

BIALYSTOK TO BIRKENAU

Central Europe, borders of 1937.

To the beloved memories of my father Chaim, my mother Esther, my brother Aleksei, and our former friends and neighbours in our hometown of Wasilkow, Poland, all but three of whom were murdered by fascist Poles and German Nazis in World War II.

INTRODUCTION

BY SIR MARTIN GILBERT C.B.E., D.LITT

It is a great honour to be asked to write this introduction. When I met Michel Mielnicki in Vancouver, I could feel the strength of his character, and something of the pain of his suffering. Since 1945 he has been a Holocaust witness, which, as he recounts, has been its own kind of hell.

Michel was born in a small town, Wasilkow, in eastern Poland, a few miles from the city of Bialystok. Of the towns 5,000 inhabitants, 1,500 were Jews. After the German conquest of that region in the summer of 1941, he spent fourteen months in the ghetto of Pruzany. From there he was deported with his family to Auschwitz, where his father was murdered. Later he was a slave labourer, first at Buna, then at Mittelbau-Dora. He was liberated in Belsen.

Even from this brief outline of Michels story it is clear that he has much to tell. The details in the book are rich and rewarding. He describes his childhood in Wasilkow with particular charm the lost world of pre-War Polish Jewry. Even during the War, his memories of the earlier years were to haunt, and to serve him: Sauerkraut, warmed in a little oil, then mixed with mashed potatoes, was something I fantasized about as a half-starved inmate in Birkenau, or as I lay at deaths door too weak from hunger even to move from my bunk when the British army liberated Bergen-Belsen in 1945. It was memories of his mothers cooking, he attests, that gave him, while in Birkenau, the saliva necessary to chew bread that was at least twenty-five percent sawdust.

Childhood, with recollections of dodging from time to time the Polish anti-Semites while on the way to school, was followed by the German invasion of Poland, when Michel was twelve. He vividly recalls how his father took him into Bialystok to see the bodies of some of the several hundred Jews who had been murdered there in the few days before the German army was replaced by the Soviet forces. I dont know whether my father saw our future clearly then or not, but in his own very particular way, he was preparing me to survive it by making me, at least in part, immune to some of its horrors.

The period of Soviet rule, from September 1939 to June 1941, saw Michels father working for the Soviet secret service. It is my firm belief that no one was ever murdered at my fathers behest, Michel asserts. But so hated did his father become that because I was Chaim Mielnickis son, I found myself the target of Polish bullets when I returned to Bialystok after the War.

Soviet rule brought unexpected benefits. This part of Michels memoirs, which includes his bar mitzvah, throws light on a neglected period of Jewish history. Among other things, the pre-War Polish quota system for Jews in higher education was swept away. He himself, aged fourteen, took up photography, and, by taking photographs of Russian soldiers that they would then send to their parents and sweethearts, earned enough money to buy a motorcycle.

The German occupation began in June 1941. With his blond hair masking his Jewishness, Michel joined a bread queue. A Polish Christian classmate volunteered to help the Nazi guard point out Jews in the lineup, and Michel was forced to leave it.

The torments of the Holocaust did not destroy Michels sense of right and wrong. For me, the two most powerful sentences in his book are his statement: When I was liberated from Bergen-Belsen in 1945, I could not bring myself to join my colleagues in capturing and killing our former SS guards. I turned away when they were being beaten to death, saying that this was a matter for God, or for the law courts.

It was the Poles, not Germans, who caused the first mass murder of Jews in Wasilkow. Michel does honour to those first victims by naming them (the naming of names is so important in the Jewish recognition of the merit and value of each individual). Thus he identifies the orchestra leader, Avreml Polak, his brother-in-law, Dovid Shrabinski, the crate-makers son, Motke Spektor, Archik the Greek, and a fine artist by the name of Shie Mongele, dragged from their beds and clubbed to death in the yard of a textile factory. How do I know this? I saw their bodies. Not only that, as one of those who were forced to bury the bodies, Michel was present when the two German soldiers brutally assaulted and then burned to death the communitys much-respected shochet (ritual slaughterman), Walper Kowalski. I was haunted by the smell of burning flesh. Of course, I did not yet know that I was going to a crematorium where I would smell it all the time, day and night.

With Wasilkow under German rule, Michel witnessed yet another terrifying pogrom carried out by local Poles. He saw from his window one of our very pregnant neighbours being beaten to death with clubs and two-by-fours, and heard a Pole call out to his fellow-looters as they rampaged through the house next door: Dont damage, dont damage, its all ours. By the time German soldiers intervened to stop this Polish slaughter of Jews, two dozen more had been murdered.

From Wasilkow, the Mielnickis went to Bialystok. Michels descriptions of the Bialystok ghetto are haunting. He tells of the newborn babies whose little lives had been snuffed out by mothers unable to feed them. From Bialystok, to avoid Chaim Mielnickis arrest on Gestapo orders, the family went to Pruzany, another ghetto, and another stage of the harrowing saga. There, during the next fourteen months, hunger and privation took its steady, relentless toll. By the time we left Pruzany in December 1942, we all looked like ragamuffins which served further to destroy our self-esteem, and thus weaken by another degree or two our ability to resist the Nazi death machine.