Edited Books

No More Masks! An Anthology of Poetry by Women (with Ellen Bass), 1973.

Women and the Power to Change (with Adrienne Rich), 1975.

Women Working: Stories and Poems (with Nancy Hoffman), 1979.

Everywomans Guide to Colleges and Universities (with Suzanne Howard and Mary Jo Boehm Strauss), 1982.

With Wings: Literature by and about Women with Disabilities (with Marsha Saxton), 1987.

Tradition and the Talents of Women, 1991.

No More Masks! Second Edition, 1993.

Almost Touching the Skies: Coming of Age Stories (with Jean Casella), 2000.

The Politics of Womens Studies:

Testimony from Thirty Founding Mothers, 2000.

Her mind closed stubbornly against remembering, not the past but the legend of the past, other peoples memory of the past, at which she had spent her life peering in wonder like a child at a magic-lantern show.... Let them tell their stories to each other. Let them go on explaining how things happened. I dont care. At least I can know the truth about what happens to me, she assured herself silently, making a promise to herself, in her hopefulness, her ignorance.

Katherine Ann Porter, Old Mortality

Knowledge is always the inseparable twin of pain and suffering.

Sashi Deshpandi, Small Remedies

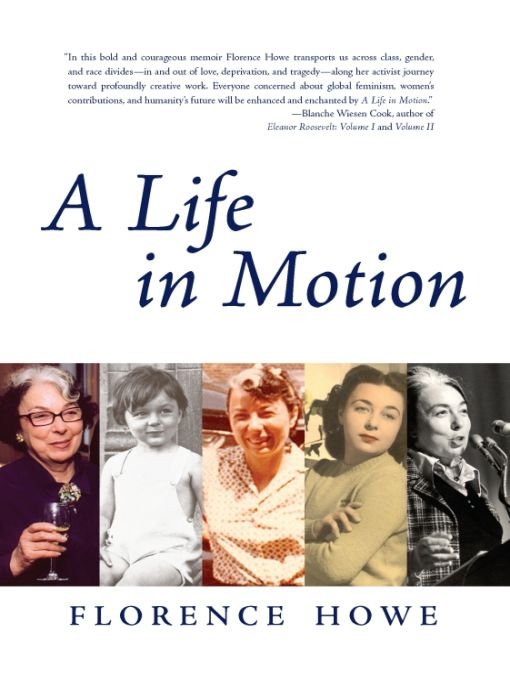

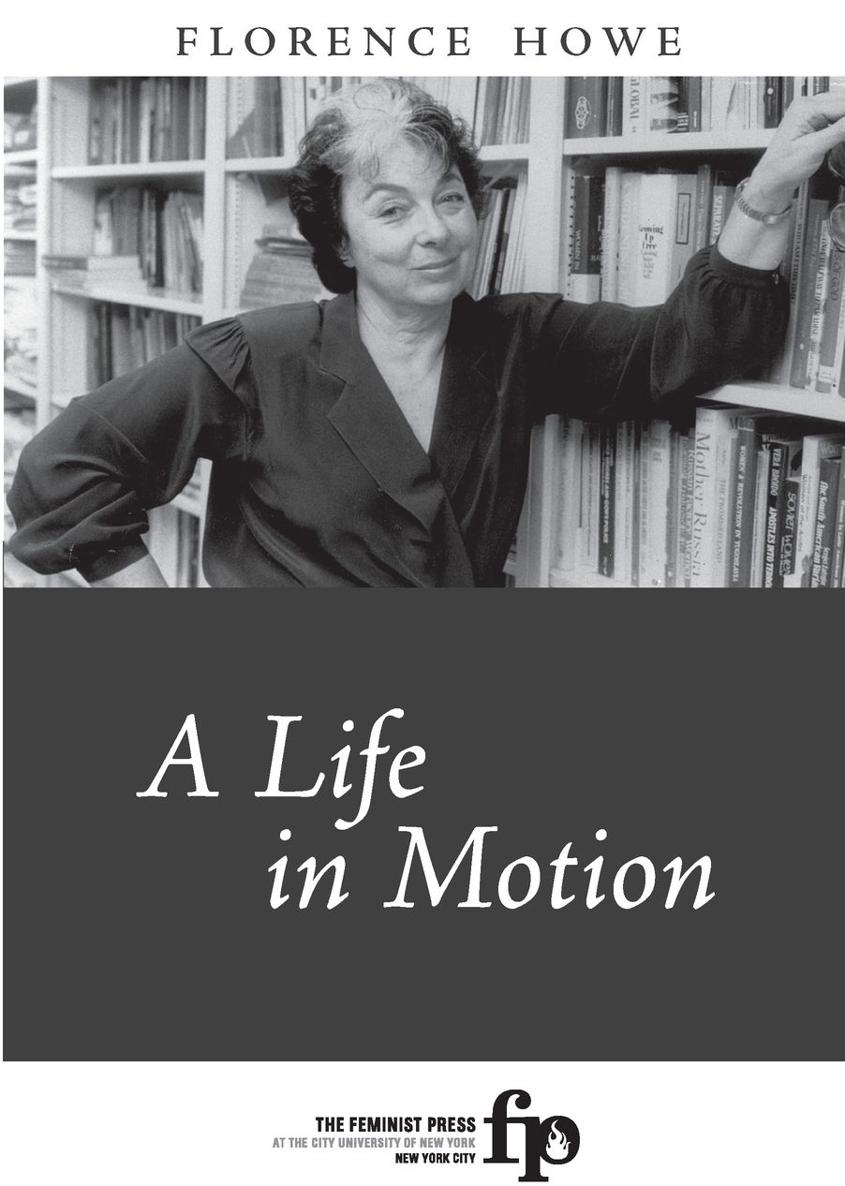

Prologue: Memory, History, and the Missing Creative Bone

As a book editor, I have usually urged writers to begin by explaining why they have written their books. What was their goal? Who was their inspiration? And, at the same time, I have also suggested that, in a concluding piece, perhaps they would like to explain whether they have accomplished their purpose. No matter that I knew the formula, I could not at first clarify the ingredients of my own book. No matter how I shook the contents, I could not then pull out a narrative line that moved from one year to the next. When I hired a professional consultant who had once been a notable editor, she said that I had to write either an autobiography or a memoir. Since I was in my late seventies when I met with her, she thought I didnt have time enough to write an autobiography, for that would entail years of research, but perhaps I could write a memoir simply from memory. That is, if I could write. There, then, was the nub: Could I write? Was I a writer?

But setting aside that question for a moment, as I explained to the consultant who knew nothing about me, I had two quite different kinds of stories to tell, and for one of these I did have rapid access to researchin my files of correspondence, records of meetings, and forty years of lengthy journals typed often daily at home and written in notebooks when I was traveling in the years before computers. Thus, for the story of the Feminist Press, I had historical documents in hand along with my own contemporary perceptions, year by year, day by day. I could write an account of the forty-year history of an institution I had helped to found and had stayed with to the present moment. And I had many reasons for wanting to write that history.

So, why not simply write a history of the Feminist Press?

Because there were other questions I longed to name, to unravel, even if I could not always answer them neatly. One might call this the backstory: Who was this person who helped found the Feminist Press and then stayed with it for forty years? Why did I have a few very sharp memories and so many blanks? Why was my life so affected by movesfrom school to school, from home to hospital, from a working-class Brooklyn household to an Upper East Side Manhattan high school, from plebeian Hunter College to waspy Smith College? Why could I not part with my childhood desire for a loving family? Why, though I left my first three husbands, did I not want to lose the fourth, though I knew he was not always as loving as the others? What motivated my life?

Like many young women of the 1950s, I wanted marriage and a family. The first mystery, therefore, is why I heeded my Hunter College mentors whose advice sent me away from those goals. My uneducated father understood that when he told me I would never have a normal life. Though I didnt believe him at the time, I never forgot his prediction. He was right, of course.

Janet Zandy, my dear friend and the first reader of this book, a professor of English at Rochester Institute of Technology, saw as inspiration for my life the motto of Hunter College: mihi cura futurithe care of the future is mine. As a wise theorist of working-class life, Janet saw that the experience at Hunter fortified my childhood battle against my mothers insistence that nothing can be changed and her certainty that a woman had to get used to living in some measure of misery. My mother had endured misery, and, she was saying, so would I. From my earliest drafts, Janet surmisedand I acknowledgedthat Hunter opened my eyes to the world and all of its possibilities for movement and change.

In the early 1990s, Janet wrote to ask me whether Id like to contribute an essay to a volume she was preparing called Liberating Memory: Our Work and Our Working-Class Consciousness. She wanted me to write about my origins and how they were connected to the Feminist Press. At first, I was dubious about her theoryand I told her there was no connection. At the same time, I told her that, because I was depressed about my mothers Alzheimers, I had begun to write a portrait of her life in the hospital. Send me what youve got, Janet said. And from there, she encouraged me to write a bit more about my mother in other times, including her visits to the Feminist Press office. Before I had finished the essay, it was clear that, indeed, there was a connection, though I was still puzzling it out. So, Janet was right, too.

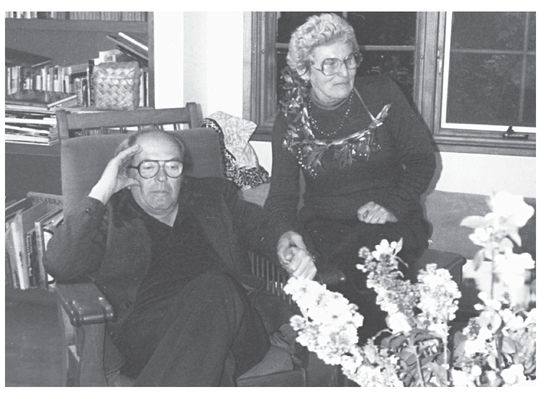

Janet Zandy and me, circa mid-1990s.

But what was not part of that essayand the puzzlewas the entrance into my life of Tillie and Jack Olsen, the working-class parents so different from my own. In 1971, I was forty-two when I first visited them in San Francisco. Tillie was fifty-nine, and Jack was sixty. They were the first to hear the stories of my family, and the first to provide some comfort, some kindness to soothe the raw grief I could feel about my childhood miseries, my fathers death, and my mothers stingy ways. And I vowed then that, if I ever wrote a memoir, I would dedicate it to them. Publicly, I always cite Tillie as responsible for the most important aspect of Feminist Press workthe gift of her reading list, which led to the discovery of specific lost women writers and the reshaping of the American literary curriculum. But I have not cited her for mothering me through various crises of my personal life and my life at the Feminist Press. She and Jack were, for many years, the people I went to for advice and comfort.