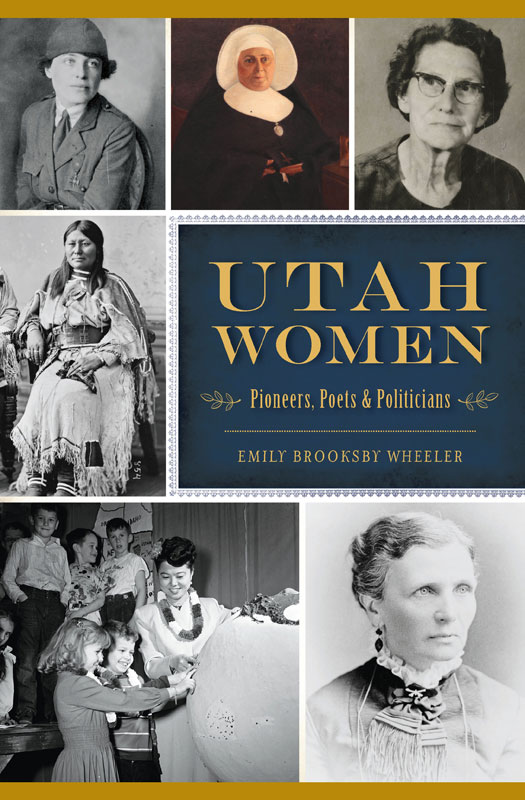

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2019 by Emily Brooksby Wheeler

All rights reserved

First published 2019

E-book edition 2019

ISBN 978.1.43966.851.1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019947301

print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.242.7

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

PART I

ON THE FRONTIER

The western frontier was harsh, gritty and challenginga mans world, but a womans world too. Women in the West enjoyed freedoms unavailable to their eastern sisters, like voting, owning land and pursuing careers in medicine or law. The frontier also had plenty of opportunities for the quieter occupations that women often pursued without fanfare, such as nursing, teaching and mothering. In large and small ways, women shaped Utah and the West alongside their fathers, brothers and husbands.

Utah was unusual among frontier states and territories because of the dominant role the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) played in its history, but it still shared many features of the Old West: Native Americans struggling against the loss of their lands; mountain men and explorers forging trails westward; miners dreaming of wealth in boom-and-bust towns; and lawmen, desperados and cattle barons battling for control of towns and rangelands. Women played a role in all of these events.

Some of the women in this volume are well-known heroes, with statues and memorials, their accomplishments found in textbooks. Others are almost lost to history, saved only by a document or two that happened to survive the years. And perhaps that is what makes them so interesting: they represent many other women whose voices are silent to us but whose stories were nonetheless as remarkable as the women featured in these pages.

Chapter 1

CHIPETA

Ambassador for Peace

In 1845, a band of Utes came across an abandoned Kiowa Apache village. The inhabitants of the village had been massacred, probably by an enemy tribe, but the Utes found one survivor in the ruined camp: a twoyear-old girl. They took her in and named her Chipeta. The little girl would play an important role in negotiating the future of her adopted people.

Chipeta was born just a few years before the Utes world changed forever. The change had been on the horizon for some time. Since the early 1800s, the United States and Spain (later Mexico) had disputed ownership of the Rocky Mountains in what would become Colorado and Utahthe traditional home of the Utes.

Prior to the 1840s, fur trappers, explorers and Spanish traders made occasional intrusions into the Utes territory, but the Utes still lived independently. They traveled in groups called bands, hunting and fishing in the mountains and meadows that had been their home for centuries.

In 1847, a group of pioneers from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latterday Saints (Mormons) arrived in the Rocky Mountains, fleeing religious persecution in the East. They were the first of many permanent settlers. The following year, the United States won the Mexican-American War and took control of a vast swath of territory extending across the Ute lands to the West Coast. The Utes had just become part of the United States of America, though they were not recognized as citizens. In the same year, gold was discovered in California, bringing a flood of people west in 1849.

Ouray and Chipeta in 1880. Brady-Handy photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

At first, these changes had little impact on Chipetas life. She grew up with the Uncompahgre Utes on the edge of the newly delineated Utah Territory. Established trails took most migrants north or south of her home. She came to know a young half-Ute, half-Apache man named Ouray. Ouray had been married, but his wife died, leaving him with an infant son. Chipeta helped care for the young boy, and Ouray was impressed with her. In 1859, when she was sixteen and he was twenty-six, she and Ouray married.

On the edge of their world, in what would soon be called Colorado, prospectors had discovered gold in 1858. The previously ignored Ute lands were now of great interest to the United States government.

In 1860, Ourays father died, leaving Ouray as the leader of his band. The next year, Colorado became its own territory, carved out of the Utah and Kansas territories, and Ourays people were a part of it. Tensions heightened between the native peoples and the settlers, fueled by the desire of each group to use the land for its own purposes. The government assigned Indian agents to the Utes to help prevent conflict. Explorer and mountain man Kit Carson was friends with Ouray and Chipeta and recommended Ouray as an interpreter and liaison for the Indian agent. Ouray had spent his childhood in New Mexico and spoke Spanish, English, Ute and Apache, and he understood both white and Native American culture.

This put Ouray and Chipeta in a difficult situation where they were viewed with mistrust by their own people and by the Indian agents. Adding more heartache to their lives, Ourays only son from his first marriage was kidnapped by another tribe, and the Utes were never able to find him.

Chipeta did not have any children. She mourned the loss of her foster son and wanted to stay close to Ouray. Though Ute wives were usually not involved in their husbands travels or business, Chipeta accompanied Ouray on his journeys. While he conducted formal meetings with men, Chipeta befriended the wives and other women and gathered more informaland honestopinions about problems with white settlers, the U.S. government and other tribes.