First published 2000 by Ashgate Publishing

Reissued 2018 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright Kevin Allen, 2000

The author has asserted his moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

A Library of Congress record exists under LC control number: 00023684

Typeset in Garamond by The Midlands Book Typesetting Company, Loughborough, Leics.

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-73208-7 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-315-18862-1 (ebk)

The most significant event in English musical history during the twilight days of the nineteenth century was the arrival in London in 1878 of the Jaeger family from Dsseldorf. They came as refugees from Bismarckian misrule of Germany. The second son of the family, the eighteen-year-old August, was keenly musical. Otherwise knowledgeable and with good English, apparently without difficulty he found work with the firm of George Washington Bacon & Co., Map and Chart Sellers and Publishers. Apart from work he devoted himself to learning about English music through earnest membership of two choirs: the Novello Oratorio Choir conducted by Sir Alexander Mackenzie; and an amateur choir, with many German members, partial to Brahms, conducted by the Austro-Hungarian Hans Richter. In 1890 Jaeger successfully applied for the senior post in the Publishing Department of Novello, which was responsible for much of the music then being used by choral societies.

In consequence of his appointment, a new future for English music was determined. Jaeger not only supervised the publication of music accepted by the firm (normally requiring the composer to undertake the cost of publication!) but submitted it also to critical examination.

A problem for Jaeger was that there were virtually no professional composers; a livelihood otherwise depending either on the post of organist in a cathedral or, more infrequently, on the post of Professor of Music at Oxford or Cambridge. Of that order, the most senior representatives were Stanford at Cambridge, and Parry at Oxford the latter, however, being independently wealthy. Walford Davies, at the time, was Organist of the Temple Church in London and Professor in a new post in the University of Wales.

Edward Elgar in 1890 was, on the other hand, solely a composer. His eventual brief tenure in the first Chair of Music in the new University of Birmingham in 1906, however, remains to this day eponymously honoured in the tide of the senior Chair of Music.

Such serious examination of new music as there was, was taken from public performance. Jaeger, however, established his credentials as critic by writing copiously on new music in the Musical Times (published by Novello). During his time the editors at Novello were E.F. Jacques (until 1897) and F.G. Edwards. The first mention of Edward Elgar in the Musical Times, in 1893, commented on the poor audience in Worcester Cathedral, during the Three Choirs Festival, for the first performance of his choral work, The Light of Life. Mr Elgar, observed the critic, was still a young man, his sympathies with orchestra rather than voices, and in need of counselling. But he is no wayside musician whom we can afford to pass and forget. Still in the Musical Times, three years later, in an account of the Cheltenham Festival, progress in reputation for the provincial composer was slow in coming: A musician from Malvern, Edward Elgar, appeared at this Festival as conductor of an orchestral work of his own, a Sevillana.

Gradually Elgar moved forward with a number of choral works and part-songs accepted and published by Novello. In 1896 there was King Olaf and, a year later, the Imperial March and The Banner of St George. In the provinces Elgar was now establishing a place of his own.

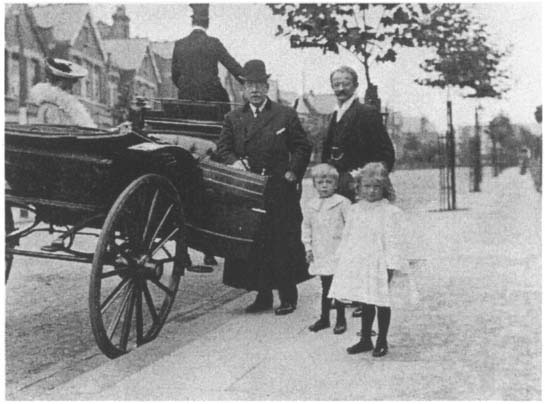

At this point, at which serious exchange of correspondence began, a graded course for the composer was enshrined under Jaegers protection and encouragement. Then the mutual passage of letters began those of Elgar often marked with characteristic and evocative drawings. When it was advertised in The Sunday Times of 5 March 1899, that Mr Elgar intended to follow sad patriotism into a symphony to be dedicated to the late and heroic General Gordon, for performance at the next Worcester Festival, Jaegar called a halt. Elgar was not yet ready, he determined, to compose a symphony. What he did compose in the last year of the century was the Enigma Variations, with its own now immortalized tribute to Jaeger as Nimrod.

Elgars letters to Jaeger vividly show the extent to which he took Jaegers advice on details of scoring. This remains the case in respect of virtually every major work composed during Jaegers tragically short lifetime. On 2 June 1899 a characteristic exchange of thoughts found Jaeger suggesting that Elgar should go to a musical festival in Bonn, which Elgar considered an attractive possibility. Otherwise he had this to say to Jaeger: I want you to get a further opinion about your nasal business: I have asked a doctor friend in town who recommends Greville Macdonald. I will remind you of this when I am up again next week & well talk it over. Ominously for Jaeger, this was the beginning of an end.

Whatever else Jaeger achieved passes into insignificance beside his involvement with The Dream of Gerontius. As is well known, the time allowed for the production of such a major and controversial work for an important Festival set a virtually impossible task for the composer to complete, for the publisher to provide the parts, and for the performers to achieve a successful first performance. In their preparations, Elgar and Jaeger probably for the only time in their relationship - found themselves in disagreement. Elgar knew Newmans mind and thought; Jaeger was less than indifferent about the text. The first performance of