ANGLO-RUSSIAN RIVALRY IN CENTRAL ASIA: 18101895

Anglo-Russian Rivalry

in Central Asia: 18101895

GERALD MORGAN

With an Epilogue

by

GEOFFREY WHEELER

First published 1981 in Great Britain by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park,

Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

270 Madison Ave, New York NY 10016

Transferred to Digital Printing 2006

Copyright 1981 Gerald Morgan

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Morgan, Gerald

Anglo-Russian rivalry in Central Asia, 18101895

1. Eastern question

2. Great Britain Foreign relations Russia

3. Russia Foreign relations Great Britain

I. Title

950DA376.G7

ISBN 0-7146-3179-5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

Photoset in Times by Saildean Ltd and

Publisher's Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original may be apparent

To Geoffrey Wheeler without whom this book would never have been written; and to Anna Hunter for so cheerfully struggling with my early drafts.

Contents

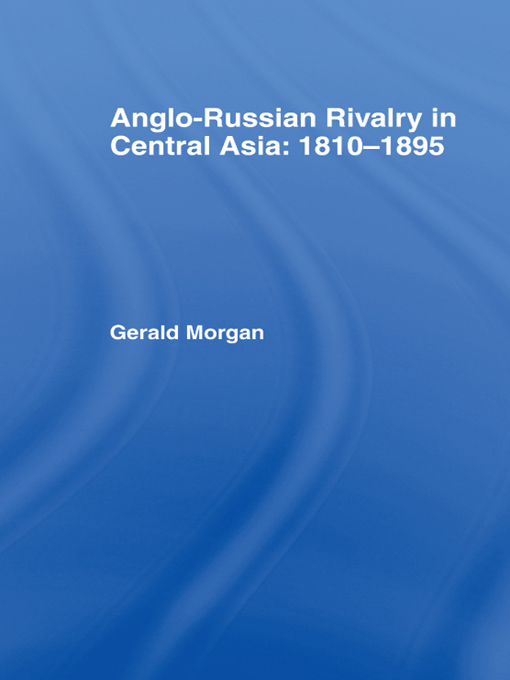

| Central Asian Khanates in the mid-19th Century |

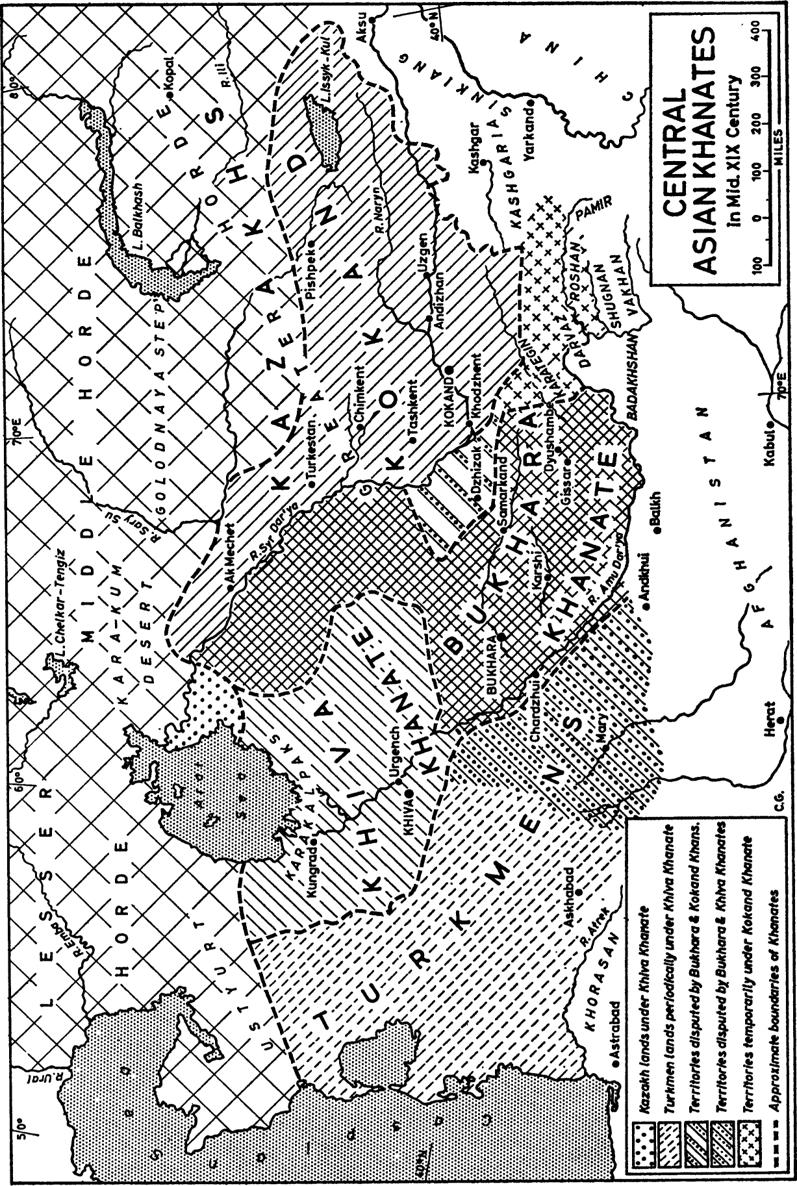

| Central Asia |

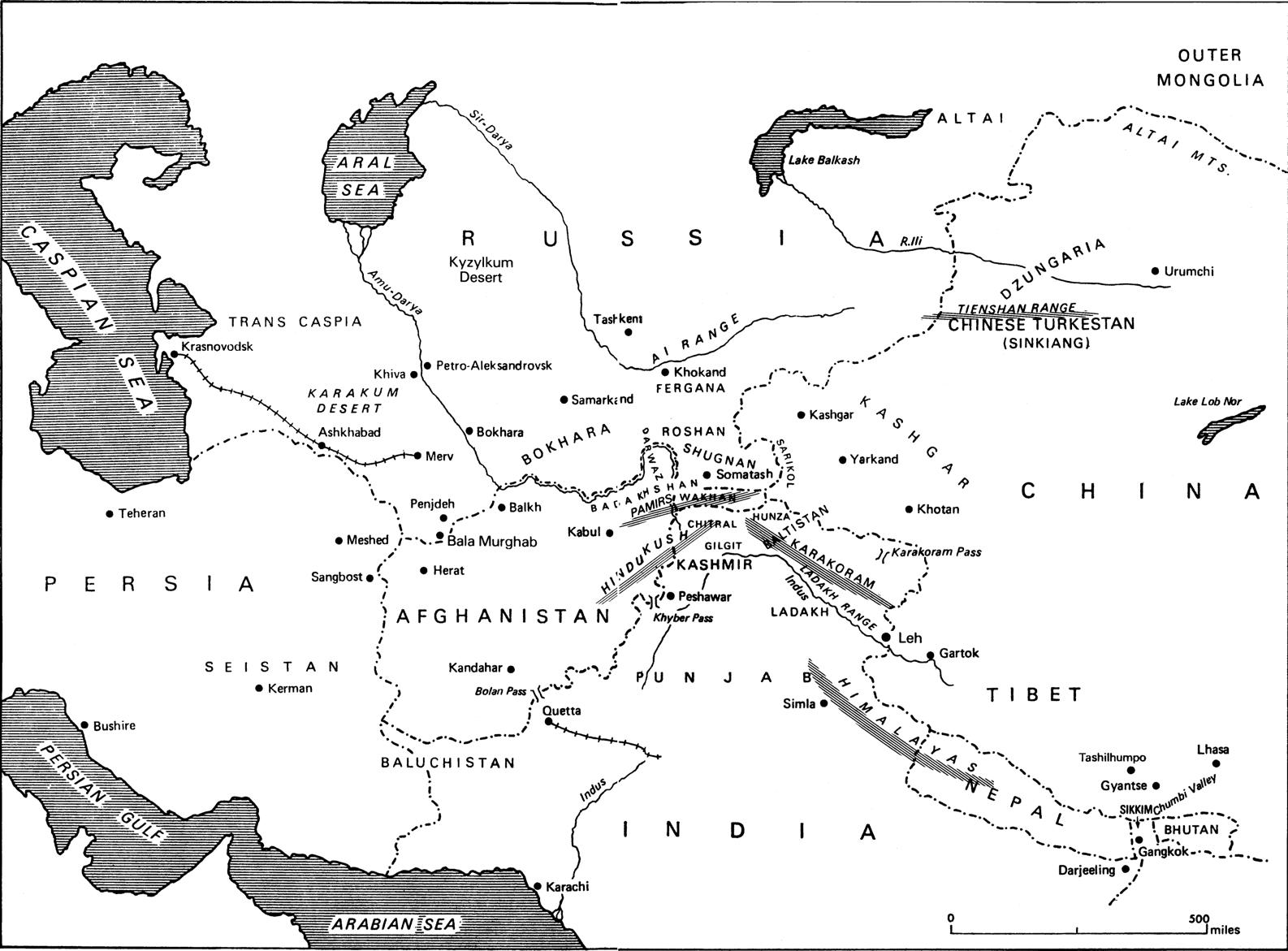

| Russian Conquests in the 19th Century |

| Chapter 1 |

| Chapter 2 |

| Chapter 3 |

| Chapter 4 |

| Chapter 5 |

| Chapter 6 |

| Chapter 7 |

| Chapter 8 |

| Chapter 9 |

| Chapter 10 |

| Chapter 11 |

| Chapter 12 |

| Chapter 13 |

| Chapter 14 |

| Appendix 1 |

| Appendix 2 |

| Appendix 3 |

Maps on pp. ix and xii reproduced by permission of Geoffrey Wheeler from his book The Modern History of Soviet Central Asia.

Preface and Acknowledgements

In the course of research for the life of Ney Elias, the remarkable nineteenth century explorer in Asia and for twenty odd years political agent on and beyond the frontier of British India, I came across much interesting material and food for thought which could not be included in the biography. One intriguing subject was the changing British policies dealing with the supposed threat of an invasion of India, and for that matter of Afghanistan, by Russia. Although he contributed so much to Indias defences, Elias never believed Russia had any such intention. But many, perhaps a majority, did, including Governors-General, Viceroys and Tory publicists; and the belief still lingers. It was always called the Great Game.

It was Colonel Geoffrey Wheeler, founder of the Central Asian Research Centre, after wide experience in Iran and still a foremost authority on the region and on Russian history of the time, who pointed out to me that no comparative study of the century of rivalry for the control of Central Asia, in particular of Russias intentions in the well-known words of the Duke of Wellington guessing at the other side of the hill had ever been undertaken. He urged me to write a book dealing with these and other relevant issues. Here is the result, and I hope it will clear away a few misconceptions and put the whole of the period of the Great Game into better perspective. I had actually finished the final draft just before the revolutions in Afghanistan and Iran, but as this book is history not prophecy I have only thought fit to alter the very last sentence of the final chapter. Whether or not history repeats itself, this study may incidentally be of some help to those trying to follow and understand current events in this confused region where so much is at stake.

My first acknowledgement must be to Geoffrey Wheeler. Not only did he put me on to translated Russian works I should otherwise never have found but he edited every chapter, answered my innumerable questions usually from his phenomenal memory and finally contributed the important Epilogue which will still further enlighten readers, summarizing events from 1895 when this book ends, as far as is possible up to the beginning of 1981. I can never thank him enough. More formally once again I have to thank the staff of the India Office Library and Records (notably Martin Moir) for their invaluable and willing help. I am grateful to the Secretary and the Editor of the Royal Society for Asian Affairs (formerly the Royal Central Asian Society) for the use of the Societys archives and of material which has appeared in the Journal. Other material has also previously appeared in History Today. I am grateful to Dr G. J. Alder of Reading University for two of his lucid papers and for other help.

I have much enjoyed the frequent letters of encouragement from John Keay, author in particular of the delightfully written and informative book The Gilgit Game (1979). Finally my thanks are due to Mrs Barbara Fitness of the Foreign Office for her impeccable typing of the final draft, and to Peter Howard for reading the proofs.

G. M.

Introduction

Although the term is in general use, Central Asia has never been a clearly defined region. In the nineteenth century it was taken in Britain as stretching from the Caspian Sea in the west to the Kansu province of China in the east, and from Western Siberia in the north to the Himalayan approaches to British India in the south. In modern maps this area is shown as occupied by the Kazakh, Turkmen, Uzbek, Kirgiz and Tajik Soviet Socialist Republics, the Sinkiang-Uygur Autonomous Region of China and by the independent state of Afghanistan.

Physically, the western, now Soviet, part of Central Asia can be divided into four regions: the steppes of what is now the northern part of the Kazakh SSR; the semi-desert of the rest of the Kazakh SSR; the desert region lying to the south of the semi-desert; and the mountain region of which the main features are the Tien Shan and the Pamirs. Sinkiang consists of a large tableland with a high proportion of desert. From a military point of view the mountainous terrain of Afghanistan is the most difficult, while the Pamir constitutes a total barrier.

The regions climate is one of extremes, the temperature ranging from minus 60 degrees Fahrenheit in the north and in parts of Afghanistan to 120 degrees Fahrenheit in the Amu-Darya (Oxus) basin. Throughout the whole region the population has always been sparse, and during the nineteenth century its total probably never exceeded 20 million. The indigenous population has always been Muslim, being made up of various Turkic and Iranian elements, of which only the Tekke Turkmens and the southern Afghans (Pathans) have shown themselves to be warlike in the past. During the whole of the nineteenth century communications were poor, living conditions primitive, and supplies for an invading army hard to come by.