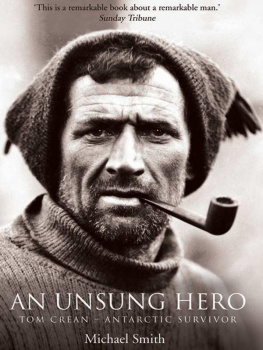

AN UNSUNG HERO

TOM CREAN ANTARCTIC SURVIVOR

Michael Smith

The Collins Press

Notes

T emperatures used in this book, unless otherwise stated, are in Fahrenheit, the measurement used at the time. In many cases approximate conversion to the now widely used Celsius scale has been added in parenthesis. (To convert F to C deduct 32, multiply by 5 and divide by 9.) But, as guidance, the following useful examples may be helpful to those unfamiliar with Fahrenheit.

| Fahrenheit | Celsius |

| 98.4 | 36.9 (body temperature) |

| 32 | 0 (water freezes) |

| 0 | 18 |

| 10 | 23 |

| 20 | 29 |

| 30 | 34 |

| 40 | 40 |

| 50 | 45 |

In line with the measurements used at the time, many of the distances are measured as geographical or nautical miles, which is 1/60th of a degree of latitude, or equal to 2,026 yards (1.85 kilometres). Others are stated as statute miles, which are equal to 1,760 yards (1.6 km). One yard (3 ft) is 91 centimetres. Some approximate conversions are provided.

Weights are given in the avoirdupois scale and approximate conversions are given in kilogrammes. One pound (1lb) equals 0.453 kg and one ton is 2,240 lb (1,016 kg).

Money is stated in the contemporary values and conversion to modern equivalents is based on information supplied by the Bank of England. This gives an approximate indication of the sums of money required in December 2007 to purchase the same goods as in Creans time. Thus it would require 84 in 2007 to buy 1 of items in 1877, the year of Tom Creans birth.

Preface

T he Dingle Peninsula, Kerry, is one of Irelands most beautiful spots, its rich mixture of rolling hills and rugged coastline jutting out into the Atlantic; nature at its best. Visitors today come from all over the world to admire the dramatic scenery.

About midway along the Peninsula, in a modest uncomplicated setting, sits the small village of Anascaul (Abhainn an Scil). It is said that Irelands last wolf was killed in the overlooking hills. But visitors passing through the main street of Anascaul are alerted by one of the last buildings they glimpse as they travel west towards the better-known town of Dingle and the Atlantic breakers. This is a small pub with a highly unusual name: the South Pole Inn situated alongside a quietly flowing river and a charming stone bridge, nowhere on earth seems farther from the South Pole.

But it is impossible to arrive or leave Anascaul without catching sight of the little building and wonder how a public house in a rural village surrounded by endless green fields on the Dingle Peninsula came to be called the south Pole Inn.

The answer, for those who linger, can be found in a small slate-grey plaque above the pub doorway. It reads:

Tom Crean

Antarctic Explorer

18771938

The South Pole Inn was the home of Thomas Crean, a local man who rose from the obscurity of a typical farming community in Kerry to become one of the greatest characters in the history of polar exploration at the turn of the century the Heroic Age of polar exploration.

Few men made a greater contribution to the annals of Antarctic exploration than Tom Crean and few were more highly respected by his celebrated fellow explorers than the unassuming Kerryman. However, for too many years, Creans contribution to the Heroic Age has been greatly underestimated, if not ignored.

The Heroic Age of polar exploration in Antarctica, which covers the first two decades of the twentieth century, produced some of historys most astonishing stories and some remarkable characters. Even today, almost 100 years after the event, people are still captivated by the tales of Scott or Shackleton, particularly the heroism and tragedies, the bravery and fortitude and the outstanding human sagas of achievement and failure which seem barely credible in modern times.

However, it would be wholly wrong to assume that all the great deeds and achievements of the Heroic Age in Antarctica were the sole preserve of Scott and Shackleton. The expeditions of the age were made up by equally important figures, not always from the officer or scientific ranks, who were vital to the success of these enterprises. But their valuable contribution has so far been mostly overlooked or at best unceremoniously lumped together with the deeds of others. Lesser known, perhaps, but no less important and certainly no less outstanding. Such a man is Thomas Crean.

Crean was a prodigious traveller who sailed on three of the four momentous expeditions of Britains Heroic Age and at that time rightly won the highest possible recognition for his outstanding achievements. He was a colourful, popular character who was one of very few men to serve both Scott and Shackleton with equal distinction.

Crean was a simple, straightforward man with extraordinary depths of courage and self-belief who repeatedly performed the most incredible deeds in the worlds most inhospitable, physically and mentally demanding climate. He was a serial hero.

Crean travelled further than most of the explorers traditionally associated with the Heroic Age and few left their mark as indelibly as the Irishman did. Appropriately enough, his name is perpetuated forever on the Antarctic Continent where he achieved his fame. Mount Crean, which extends to a height of 8,360 ft (2,550 m), stands at about 77 53 S 159 30 E in Victoria Land, Antarctica. The near 4-mile (6-km) Crean Glacier runs down to the head of Antarctic Bay 37 01 W 54 08 S on the island of South Georgia, where the Irishman was to perform so nobly.

Tom Crean is not the only one whose adventures have been overlooked by Polar historians. History has also been unkind to men like Edgar Evans, William Lashly and Frank Wild, colleagues and friends of Crean in the South. It was men like these who provided the backbone for the great expeditions which lifted the veil from the Antarctic Continent, often at a terrible price. While these men were effectively second-class citizens at a time when the British class system was so prevalent, the Heroic Age would be incomplete without their contribution.

To be fair, it has not been easy for historians to chronicle the tale of Tom Crean, a semi-literate man who, unlike so many explorers of the age, did not keep a diary or maintain a prolific flow of correspondence with friends and family. Only a small amount of Creans correspondence has survived and so, in order to piece together his life and times, we have to rely on the words and memories of his contemporaries. Fortunately, since he was a prominent figure of the Heroic Age, there are ample records of his exploits in the published and unpublished accounts of the three expeditions on which he excelled. It is no surprise, however, that much of the coverage so far has been inconsistent.

But with the combination of Creans own writings, the works of his contemporaries and the invaluable recollections of his surviving family, for the first time an authoritative and accurate account of the life of a remarkable man can be constructed.

His contemporaries had few doubts about his special qualities. Frank Debenham, who served alongside Crean on Scotts fateful last expedition and later became the first director of the Scott Polar Research Institute at Cambridge, remembered the Irishman with special affection. He once wrote:

Tom Crean was in his way, unique; he was like something out of Kipling or Masefield, typical of his country and a credit to all his three expeditions. One has only to close ones eyes for a moment to summon up his clean-cut features and his grin as he greeted one in the morning with: Well fare ye, sorr.

Next page