T HE D IE IS C AST

T he least original way to begin is to say that the war changed my life. Unlike the comedian Robb Wilton I am not entirely clear as to where I was on the day war broke out, but I do know that shortly thereafter my parents made an eccentric decision. The phoney war was a period for the average civilian, and indeed for the ordinary serviceman, when little took place and there was more boredom than excitement. I suppose this gave a great deal of time for the imagination to run riot. My mother assumed, as no doubt did every other mum, that wherever she was with her infants was where Hitler would unerringly strike. We took him very seriously and I suppose with good reason. It was not until long after the war when I first saw the Charlie Chaplin film, The Great Dictator, that I realised that there could be a funny side to the grimmest of events.

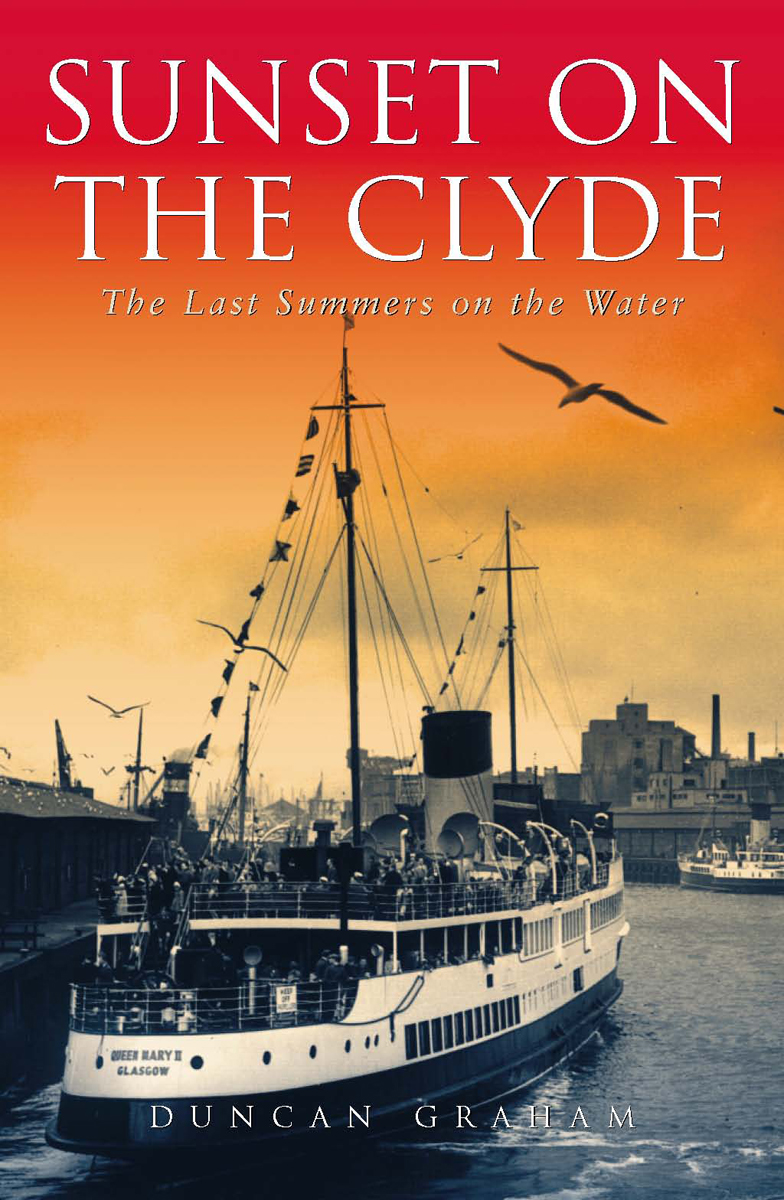

My mother decided unilaterally on an evacuation from Rouken Glen, in the suburbs of Glasgow, to Dunoon where Aunt Peggy, who represented the upper-class end of our decidedly mixed family, held both ownership and court at the Cowal Hotel in East Bay. It had to be the East Bay because what little sand there is is in the West Bay and the East Bay is therefore infinitely higher class. The Cowal Hotel shone forth like a beacon because it was, and still is, quite the tallest building in the East Bay. It is topped with distinctively Scottish dormer windows, and just where, if you stagger out from the bar on the boat, you cop your first eyeful of Dunoon. This is ironic because the Cowal Hotel was the temperance hotel in Dunoon, as its publicity literature made proudly clear. It was many years later that I discovered that other hotels had cocktail bars and lounges. Temperance, by the way, is an odd euphemism for abstinence. The visitors to the Cowal Hotel neither expected nor received even the smallest of sensations.

Behind the scenes I have no reason to doubt that in an atmosphere reminiscent of the prohibition, illicit brews passed furtively amongst the inmates. I never worked in a hotel kitchen where the staff were ever less than half-cut. It would be too much to say that I had evidence that my Uncle Jack was more temperate than abstinent, but after he retired, his wine cellar was extensive.

Recently and well into her nineties my mother remembered that for one night only principle gave way to profit. Approached by Harry Lauder to host a celebration of a lifetime in show business, it was agreed that liquor could be brought in at 6pm on the great day, but that the last unconsumed vestige should be removed without trace by midnight. The great troubadour was by all accounts in sparkling form, but, like Cinderella, left well before the witching hour.

There was a Clyde paddle-steamer, the Ivanhoe, which in the 1880s was a temperance ship. No alcohol was served on board. Anyone who visited the engines on her was not making the time-honoured excuse for nipping below to the bar. It was claimed she was successful, but an Ivanhoe Flask with a suitable capacity for a days cruise could be purchased in Glasgow before going aboard! Id like to think that her more sober passengers, who prized her yacht-like looks, her decks scrubbed a snowy white and crew in white blouses with navy blue collars, came ashore at Dunoon and made a bee-line for the Cowal.

In other ways the Cowal Hotel was typical of its time. On the ground floor to the left of the front door lay the public rooms, and to the right a resplendent dining room. Here were waitresses with spidery black legs, their black uniforms relieved only by white aprons and little caps of the kind which nurses used to wear before the NHS cuts. There was a head waiter; he seemed formidable to me but then any man dressed in tails might seem so to a three-year-old. He was to become my friend, as even in the darkest days of rationing he conjured Scotch trifle from the recesses of the kitchen. Even paying guests found him forbidding and, as was the way in those days, they had to compete for his favours. He reminds me now of that famous head waiter in New York whose obituary was said to have been At last God caught his eye.

Upstairs on four floors were the 30 or so bedrooms which could be reached by the kind of lift which was all the rage in Hollywood movies and department stores such as Copeland & Lye and Pettigrews & Stephens in Sauchiehall Street. The well in which it ran was an open tracery of girders and wire netting. Its expanding metal doors echoed throughout the hotel and its interior was dark wood and mirrors. It broke down daily, much to the distress of the more aged permanent residents. They had placed their faith in it and taken rooms on the top floor at the front for the view across the Clyde to the Cloch Light and the steamers, cargo ships and liners which thronged the Clyde in the thirties. Behind the lift shaft lay my aunts office, a visit to which, at a tender age, put me off the idea of office work for life. It fostered a distaste for bureaucracy which has grown apace.

My aunt was a semi-invalid, a martyr to asthma and spent most of her time either in the office or in her splendid bedroom-cum-sitting room on the first floor just above the canopy of the entrance, where chauffeurs handed out the guests from their splendid cars. There were more Armstrong-Siddeleys and Daimlers than Austin Sevens. At that time the room fascinated me. It was not because the furnishings were so opulent or the view so splendid, but because uniquely it had a washhand basin surrounded by all the appurtenances normally seen in bathrooms. There was nothing en-suite about hotels in 1939. Nowadays every B&B boasts of it on the little signs which are covered with a bin-bag when they are either full up or the owners have gone out for a night on the tiles.

That unique washhand basin was still there when I made my first professional visit in 1974 to what had been the Cowal Hotel. It was now the Education Offices of Argyll County Council. That year saw the setting up of Strathclyde Region (itself now consigned to history), a move so unpopular that when out for a pint I had to conceal the fact that I had become second in command of an education department which spread from Iona to the Gorbals. That very room had become the office of the Director of Education and I went there to meet Charles Edward Stewart. In the reorganisation he had become my Divisional Education Officer. Years later he told me that I appeared even odder than he had been led to believe. Instead of delivering an inspirational speech about the future of education, I had apparently banged on about the plumbing arrangements!

Dunoon was close to the Tail o the Bank which was to become one of the greatest concentrations of military and naval activity in the whole of the UK. It was from here that the great convoys were to issue forth through the boom which was constructed between the Gantocks, close to the pier at Dunoon and Cloch on the other side. The gates were drawn open and shut by dumpy boom defence vessels attached to them at bow and stern. The fear of submarine attacks on the myriad of ships which lay within was palpable even more so after Gunther Prien in U47 sank the Royal Oak in Scapa Flow. Records show that U-boats were put in to penetrate the Clyde estuary and that early in the war at least two laid a significant number of mines. In reality, however, a much greater threat lay in bombing or blitzing as it was to become known. More experienced students of war than my parents might just have worked out that there was more chance of a stray bomb landing on Dunoon than at Rouken Glen although its fair to say that the famous Glasgow park was used as a lorry dump for most of the war, ruining what had been the finest turf in any of the parks in the dear green place. The grass has not recovered even now.