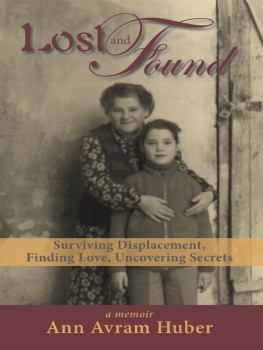

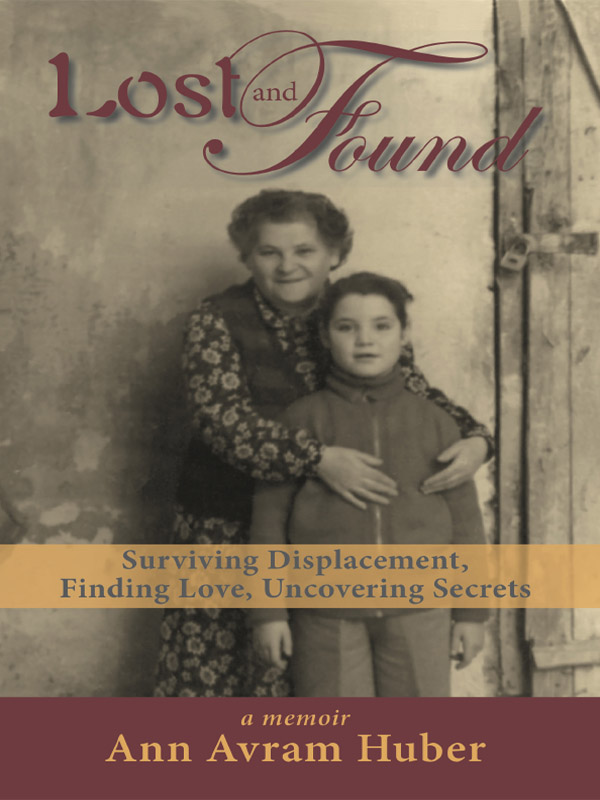

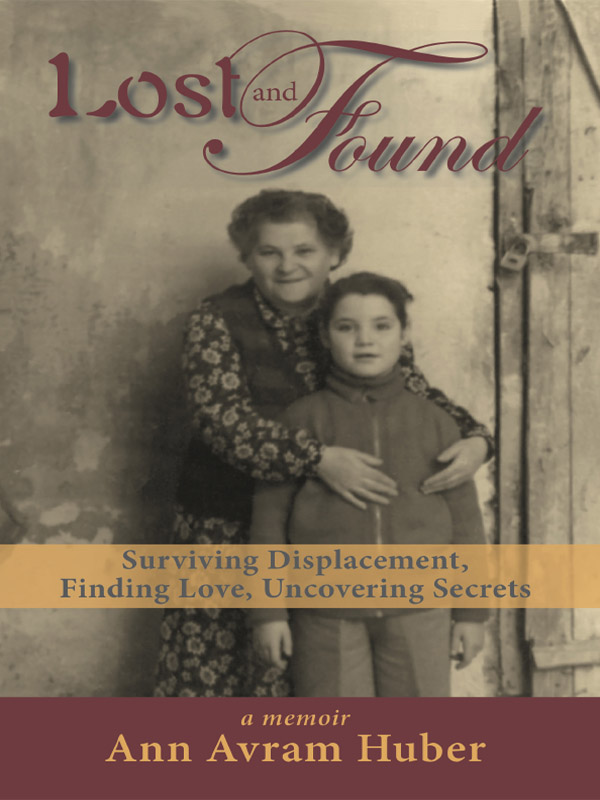

Lost and Found

Lost and Found

Surviving Displacement, Finding Love, Uncovering Secrets

a memoir

Ann Avram Huber

In Memory of

My Grandmother, SARA MARCUS

My Mother, NETTY GLEIZER

My Mother-in-Law, PESCHE HUBER

Lost and Found. Text Copyright 2017 by Ann Avram Huber All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Contact Mishpucha Books, 54 Maple Ave., Madison, NJ 07940

The names and identifying characteristics of certain persons have been changed, whether or not so noted in the text.

ISBN: 978-0-9883544-6-3

eISBN: 978-0-9883544-70

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017905741

Interior Design by Adept Content Solutions

Cover Design by Meg Souza

Published by Mishpucha Books

Madison, NJ 07940

www.Mishpuchabooks.com

Herm (exasperated):

Where were you when God was giving out patience?

Ann (feisty):

I was in the intelligence line for the second time!

Ann to Herm:

Sometimes I love you so much I think my heart will burst.

MADELINE ALBRIGHT and I share a similar history. I too was born abroad, left Europe as a child, became a lawyer, and got involved in politics. Like her, I learned only late in life that significant truths about my heritage and, indeed, who I was, had been kept from me. Why did I not become Secretary of State? To what extent was it talent or luck or the result of some other forces? To what extent was my path shaped by other peoples choices or mine? Or the tumultuous forces of history? Or was it fate?

Destiny is no matter of chance. It is a matter of choice.

It is not a thing to be waited for, it is a thing to be achieved.

William Jennings Bryan

AS A CHILD, I often tried to imagine my parents wedding day. My mother did not want to discuss her wedding and it wouldnt have occurred to me to ask my father. We never talked about the past. My fantasies drew heavily on what Id seen in romantic movies like South Pacific, because I had so few facts to go on. The only clues were the few worn, professional wedding photos among the family pictures kept in a shoebox. Perhaps I spent so much time with this box of old sepia photos because, apart from a china doll and a jar of buttons, it was the only thing I had to play with. I spent hours in our tiny apartment in Haifa, Israel, sorting, studying, and labeling the wedding pictures. Somehow, perhaps because of the way my mother brushed off the subject, I sensed a mystery. I was hungry for more information.

In those photos, my mother Netty wore a magnificent, long-sleeved gown. A veil descended from a headdress into a long train and she carried a large bouquet of flowers. They were white, was all my mother was willing to say. My father Sandu was dressed in a fashionable, immaculately tailored suit with a white bow tie, white gloves and black top hat. They made a lovely couple, elegant,beautifuland so young! Netty was 16, Sandu 24. It was 1939 in Galati, Romania, three months before Germany attacked Poland, launching World War II. The carefree, innocent faces I saw in those photos would soon be lined with worry.

Netty and Sandus Wedding, 1939.

My mother was born in 1923 in Galati, (pronounced Galatz), a large seaport about 150 miles east of Bucharest on the banks of the Danube River. She was named after her paternal grandmother, as were four of her cousins, according to the Jewish custom of naming children after deceased kin. The family kept the cousins straight with nicknamesNetty the Eldest, Netty the Shortest, Netty the Redhead. I was never certain of my mothers nickname, but I think it would translate as something like Netty the Cunning. This made sense to me:she was smart, and a survivor who navigated through a difficult and complicated life. In her later years, when I devoted a great deal of time to her care, she should have been called Netty the Cranky. If I arrived late because I was tending to my children or grandchildren, she was always unhappy. She was expert at sucking the joy out of seeing her. Annie, theyre taking advantage of you. You spoil them too much. One of my grandchildren nicknamed her Great Netty, perhaps an ironic name, or perhaps simply a contraction of Great Grandma Netty. Unfortunately for both of us, I remained the center of Nettys life well into my adulthood. She insisted she did not need friends and relied exclusively on me. Yet, until she was so old she began to fear her own death, she revealed precious little about herself: she held her emotions in check and her full story a mystery.

In the first decades of the 20th century, Galati was a thriving seaport with a population of about 100,000, including 20,000 Jews whose ancestors could be traced back to the 16th century. Galati had survived successive occupations, beginning with the Romans and later by the Turks of the Ottoman Empire. During the Ottoman occupation of the nineteenth century mob attacks against Jews were not uncommon in which Jews were either killed on the spot or driven into the Danube to drown.

By the time of my mothers birth, anti-Semitism was less prevalent than during the Ottoman rule, though always lurking. After World War I, Galati became the center of Romanian Zionism. When my mother was a young child, Galati had 22 synagogues.

Films documenting life in Galati around 1944 show tram tracks, but it seems most things were moved by horse and wagon or by women balancing large woven baskets on poles across their shoulders. Yet, my mother boasted to me that Galati had a beautiful railroad station with daily service to Bucharest. She always said the stone building with slate tiles at the Madison, New Jersey train station reminded her of Galati. A picture of Galatis old train station circa1890 shows an appealing stone building with pitched slate roof. It could have been transplanted from a quaint Swiss village and built to survive forever. When my mother talked about Galatis trains, I did not yet have any notion of the role they had played in her life.

My grandfather putting on tefillin; Mamaia, 1953.

My grandparents settled in Galati shortly after they were married. My grandfather, Carol Marcus, born in 1897 in the nearby village of Tecuci, and my grandmother, Sara, born in 1901 in the village of Podu Turkului, were first cousins who married around 1920. It was not uncommon among that culture at that time for cousins to marry including first cousins.

Although he was already quite old when I was born, I remember my grandfather well, as a gentle, kind, soft-spoken man who loved to laugh. Each morning until he passed away when I was six, I observedhim begin the ritual of morning prayers by wrapping the small leather boxes called phylacteries (containing prayers from the Torah) around his arm, hand, and fingers and on his forehead. Short and portly, he resembled my grandmother, the family matriarch whom we called Mamaia, a childish contraction of the Romanian counterpart of Big Momma which my cousin Mircea, the first grandchild, could not manage to pronounce. My grandfather became Tataia.

Next page