All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Convergent Books, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

CONVERGENT BOOKS is a registered trademark and its C colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

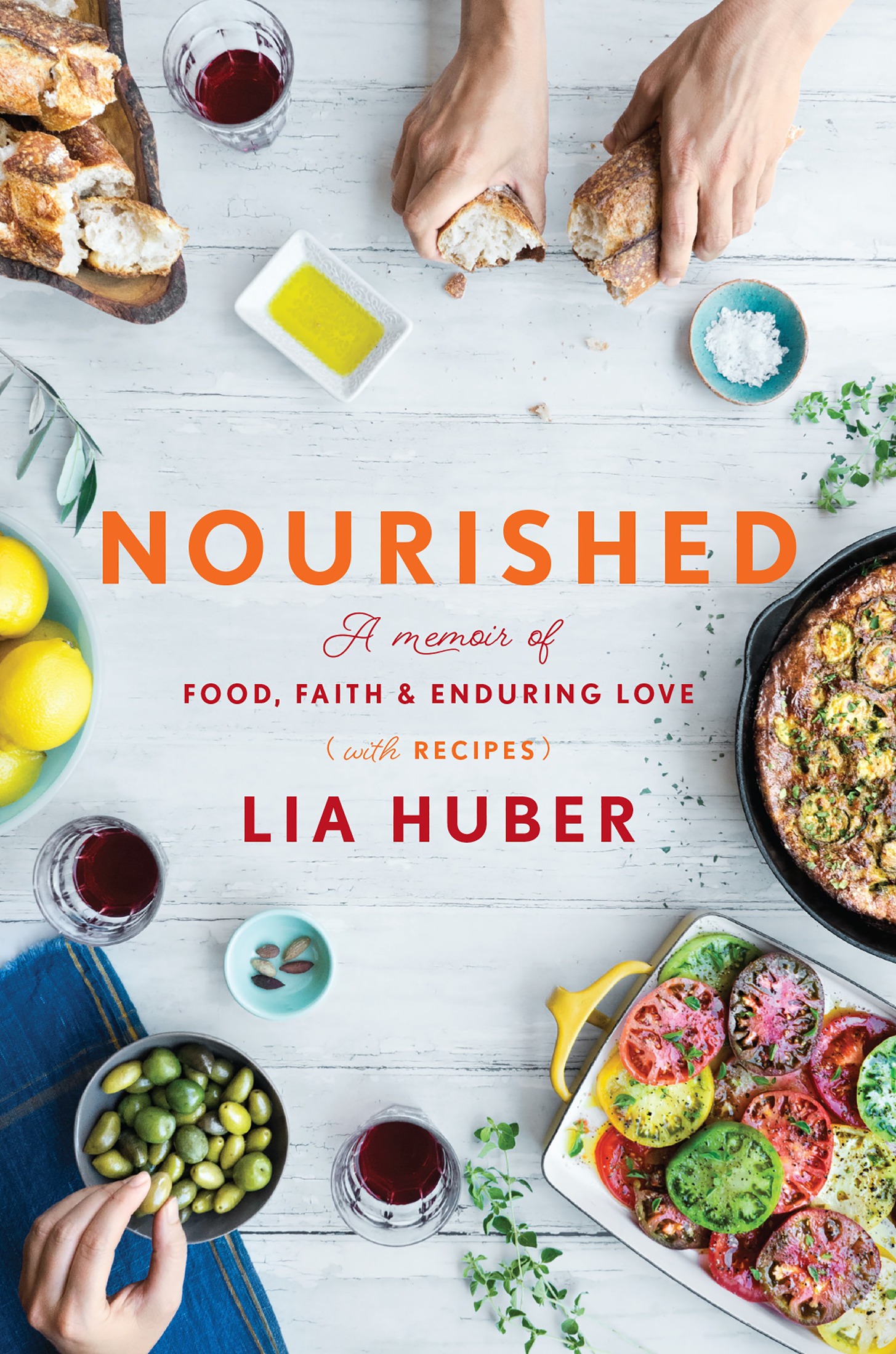

Names: Huber, Lia, author.

Title: Nourished : a memoir of food, faith, and enduring love (with recipes) / Lia Huber.

Description: New York : Convergent Books, 2017.

Subjects: LCSH: International cooking. | Food security. | FoodPsychological aspects. | Well-being. | BISAC: COOKING / Health & Healing / General. | TRAVEL / Special Interest / Adventure. | LCGFT: Cookbooks.

For Christopherfor always being willing to jump out of airplanes with me.

For Noemidont forget.

For my parentsfor teaching me anything is possible.

PROLOGUE

JULY 2012

T heyre not going to like the vegetables, the old woman in the corner of the hut mumbled through wrinkled lips and missing teeth. She was speaking in Kaqchikel, the language native to this region of Guatemala, but I understood her nonetheless. I was used to the skeptical, almost goading tenor of that sentence.

The other women, of varying ages, nodded in agreement. I stirred the giant pot perched on a rickety propane burner and pretended not to understand.

I was in Guatemala as part of a team that had traveled there to build a house for a family, and since I was also a professional cook, they had asked me to make lunch for sixty elementary school kids. A soup was strongly suggested. Me being me, I dove into the task by researching traditional soups of the region and settled on a simple chicken soup. Knowing that malnutrition statistics were dire in villages like San Rafael, I also took it upon myself to go heavy on the veggies.

Of course, when I had left our teams compound to procure said veggies the day before, my armful of giant market bags had caused many to ask, What are you doing?

Im going to buy vegetables for the soup, I answered. Inevitably, whoever they were, they would make the same face the old Guatemalan woman just did, shrug, and say in Spanish, The kids arent going to like the vegetables.

So now I knew that sentence in three languages.

When my husband and I had arrived in San Rafael along with our team, the social workers had taken us on a tour. Id expected poverty. Over half of the people in Guatemala live below the poverty line, and 15 percentlike those in San Rafaellive on the edge of subsistence. That means homes cobbled together from sticks and scraps and corrugated plastic. It means no toilets or potable water. It means that most kids are out working in the fields by the end of elementary school in order to help the family survive.

What caught me off guard was that the people in San Rafael made money by growing vegetablesprimarily squash, corn, and green beansyet kept none of those vegetables for themselves. I watched as a farmer lifted boxes of pristine green beans off his donkey, and then I turned to the social worker. I dont understand. It seems like theres plenty to have some for his family.

They have to sell everything they produce just to get by, she replied.

Poverty is a tricky thing, and Im not going to pretend to know how it feels to live each day on the brink of survival. But the wrappers crunching an inch thick beneath my feet and the sticky hands and faces of nearly every child I met were telling a story too. Surely the junk food that people were buying would cost more than what a farmer would make on the few handfuls of green beans that would feed his family.

The unspoken narrative came to the surface in that dirt-floored kitchen with the grumbled sentence Id heard in three languages. Moms were concerned their kids wouldnt eat the green beans.

A skinny, dirt-streaked boy appeared in the kitchen doorway and then scurried awaywhich, apparently, was a sign that the time had come. I ladled out bowl after bowl of steaming soup and sent it off with the helpers into the classroom.

Twenty minutes later, I realized Id served well beyond sixty bowls. Whats going on? I asked one of the helpers.

One of the women piped up from the corner with a wry grin on her face. The kids are asking for seconds. Another woman stood up and took the ladle from me, shooing me out of the room in a manner that appeared brusque. But I knew Guatemalans well enough to detect a note of affection in her gesture.

As I walked toward the classroom, I thought about my own junk-laden childhood. When I was these kids age, I would come home from school and polish off a bag of Doritos, follow those up with a half dozen Chips Ahoy, and then not touch the carrots in Moms pot roast. Our economic circumstances might be vastly different, but these kids and I could have been kin, judging from how we felt about vegetables.

The same went for the mothers grumbling in the kitchen. With their skeptical, almost antagonistic posture, they could have been stand-ins for any number of women Ive met in the United States. They told me things like, Of course you roasted a chickenyoure a chef. Im more of a KFC kind of gal. Or, Of course you made sauted mushroomsyoure such a foodie. Our familys more Hamburger Helper. And on went the explanations about how they didnt have time or training or energy to cook with real food.

But Im here to tell you that those excuses are a bunch of baloney. (Which, by the way, I used to love. Fried.) Choosing root vegetables over something out of a box isnt about being a foodie. Its a matter of life and death. I know because fake, convenient, fast food nearly killed me, and real food not only saved my life but made it richer than I ever could have dreamed.

I walked across the cracked cement where the kids had been playing soccer and through the classroom door, expecting to see piles of soggy vegetables sitting beside the bowls. Instead I saw tops of heads as the kids all but lapped up the soup. They looked up with wide, wet smiles and I asked, Le gustan el caldole gustan chayote? (Do you like the soupdo you like the squash?)

One particularly gutsy boy raised his spoon like the Statue of Liberty raising her torch and declared, Rico chayote! (Squash is delicious!) Others joined in, and soon the whole room was chanting, Rico chayote, rico chayote! I hugged each and every one of those childreneven the ones who thought hugging was uncooland walked back to the kitchen in a broth-scented bubble of euphoria.

There, too, the scene had turned convivial. The women were slurping bowls of soup and chatting with one another and, miracle of miracles, they were smiling at me. One handed me a bowl of my own and patted the seat beside her. I took it, savoring the rich stock studded with chicken and squash (it really was good), the intimacy of being hip to hip, and the warmth of the bowl in my hands.