CHAPTER ONE

A BRIEF GLANCE AT THE END

A huge cracking noise. Beneath my left hand, the sheet of rock that bears my weight suddenly comes loose. It falls on my left foot and knocks me off balance. Instinctively, I try to find something on the rock to hold on to. Nothing. Absolutely nothing. Everything is crumbling. Its all coming down.

At the last moment, I jump, turning 180 degrees, staring into the abyss, and pushing off with both feet. Everything speeds toward me. Theres no more time to think. I crash into a steep slab of rockfirst with my feet, then with my backside, and then I keep going. Im catapulted forward in a wide arc, sailing through the air. When I smash into the ground, its like an explosion.

September 15, 2005, 12:35 pMIm still alive after falling a total of 16 meters.

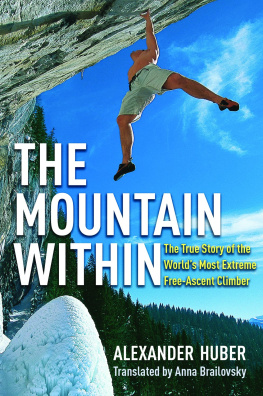

Its been two weeks since Thomas and I arrived in Californias Yosemite Valley. Weve been here so often in the past ten years that this national park has become our second home. For the millions of tourists who visit Yosemite every year, the roaring waterfalls are the main attraction. But for us climbers, its the rock formations that call to us, such as the Half Dome and El Capitan, looming majestically over Yosemite Valley. For over a hundred years these rocks have made the Valley, as its known for short, into something more than just an incomparable natural spectacle. Thousands of climbers gather here every year to seek adventure on its vertical walls. This unique collection of wild granite escapes is unparalleled in the worlda true mecca for the sport.

The rock that stands out among all others in Yosemite is undoubtedly El Capitan, and the most irresistible route on its wall is the Noseprobably the most famous rock-climbing route in the world. It was on this very route that Thomas and I had wanted to set the new record for the fastest ascent. Speed climbing. Normally, time is not the most important aspect of mountain climbing; the point is usually just to make it all the way to the top. But after all the summits have been attained and all the faces conquered, climbers begin to look for new challenges. It is in the nature of the sport that, as time goes by, the achievements become more and more extreme; one is always trying to go faster, higher, farther. On the big walls of Yosemite, too, the race was on. And so the climbing grew increasingly faster: days, hours, and minutes were shaved off the ascent times. One record after another was toppled. By the 1990s, an entire speed-climbing scene had developed, with a horde of young speed demons lining up one after the other to break each others records.

The previous year, Thomas and I had not only set a new record on the Zodiac route, but with a total time of 1 hour, 51 minutes, and 34 seconds, we had also made the fastest ascent ever of El Capitan. Nevertheless, we were not yet 100 percent satisfied. The venerable old Nose is the ultimate rock route, and setting a speed record here is the absolute pinnaclethe record that stands above all others. Only when the record on the Nose was ours would we have achieved our aim. Our last great goal in Yosemite would be accomplished.

But it wasnt only our objective that was unusual. We also had with us a fourteen-member film crew that had chosen our project as the subject of a feature-length documentary. Even before wed left home, we knew that the world of film would be entirely uncharted territory for us. After all, Thomas and I are not actors. And though we were familiar with the presence of a camera from earlier projects, we didnt have the slightest idea of how much work we were taking on. Coordinating fourteen film people is already challenge enough for the production manager, let alone the fact that we would all be climbing a mountain, to say nothing of a vertical wall.

When we arrived in San Francisco, Thomas and I were still alone. We set off by ourselves for the Valley on a mild September evening. It was the calm before the stormone last peaceful night in a little roadside motel before beginning our climb. Nonetheless, we had a slight premonition that things would soon begin to heat up.

The next morning we were supposed to meet the whole crew at 9:00 AM at a gas station inside the entrance to Yosemite, but no one came. Not at nine. Or ten. And when we were still waiting there at eleven, I tried in vain to reach someone from the production company in Europe on the telephone. Just as I was punching the fifth telephone number into my phone, Pepe Danquart, the director, arrived. Perfect communication: The crew was waiting at a station outside the park, while Thomas and I had sailed right past them, straight into the Valley.

Things went on in this chaotic manner. This was due not so much to a lack of organization, but rather to the complexity of the situation. Filming in the middle of a 1,000-meter-high wall was the ultimate example of how complicated the technical aspects of a production could be: Three cameramen and a sound engineer were supposed to be hanging on the wall. The director, with another camera and assistants, had the choice of setting up either at the summit or at the base. Sufficient quantities of sleeping bags, water, and provisions had to be in the right place at the right time, along with the terribly heavy and expensive film equipment. On top of that, some of the film crew had had very little experience with mountains. It was a monstrous logistical puzzle, as difficult to solve as the undoing of the proverbial Gordian knot.

Despite the perpetually blue California skies, the general mood blackened with each successive day of the shoot. There was hardly a day on which we were able to keep to the production plan, and tensions grew under the pressure. Nerves were raw. Heated discussions became more and more frequent. With an undertaking this complicated, there were hundreds of possible approaches. Although each person had expertise in their own field, we all had to cooperate with everyone else. In addition, the entire crew could rarely be gathered together in one place. While some were on top of the mountain, others were on the way up, still others on the way down, and a bunch more had gone to get camera equipment from San Francisco.

The situation took some getting used to. Of course, an expedition to one of the great mountains of the world is always complex. But while climbing the mountain itself is a clearly defined task, a documentary film does not take shape as a tangible product until it is finished. Furthermore, the tools that are used for mountain climbing are relatively manageable and usually fit in a single backpack. And, in a modern expedition, we climbers are the ones doing all the work.

The first day of shooting on the wall turned into an endless wait. Although everything had been well preparedthe cameras and the sound equipment were already in place before Thomas and I showed up at the approach of the Noseit still took an eternity before a single take could be filmed. Mostly, it was just little details that had to be corrected. But in the vertical, everything takes much longer. First the rope was in the frame, then it was the soundman, and then the position was too unstable. What took a matter of seconds to film on the ground turned into minutes in the vertical, which ultimately added up to hours. Nonetheless, everyone tried their best. We needed to gain experience as a team, and it took time.

Never before had Thomas and I allowed anything to come between us and our climbing goal. Yet we had agreed to this project, and from that moment on we could no longer make decisions independently. Aside from us, there were the producers, who had taken on significant financial risk; Pepe Danquart, the director; and a large team of filmmaking professionals. All of these people were now just as involved in this project as we were.