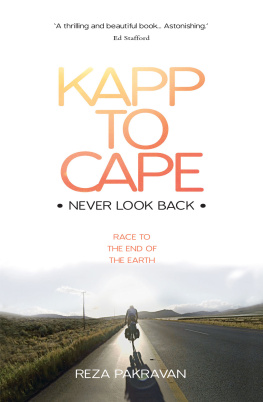

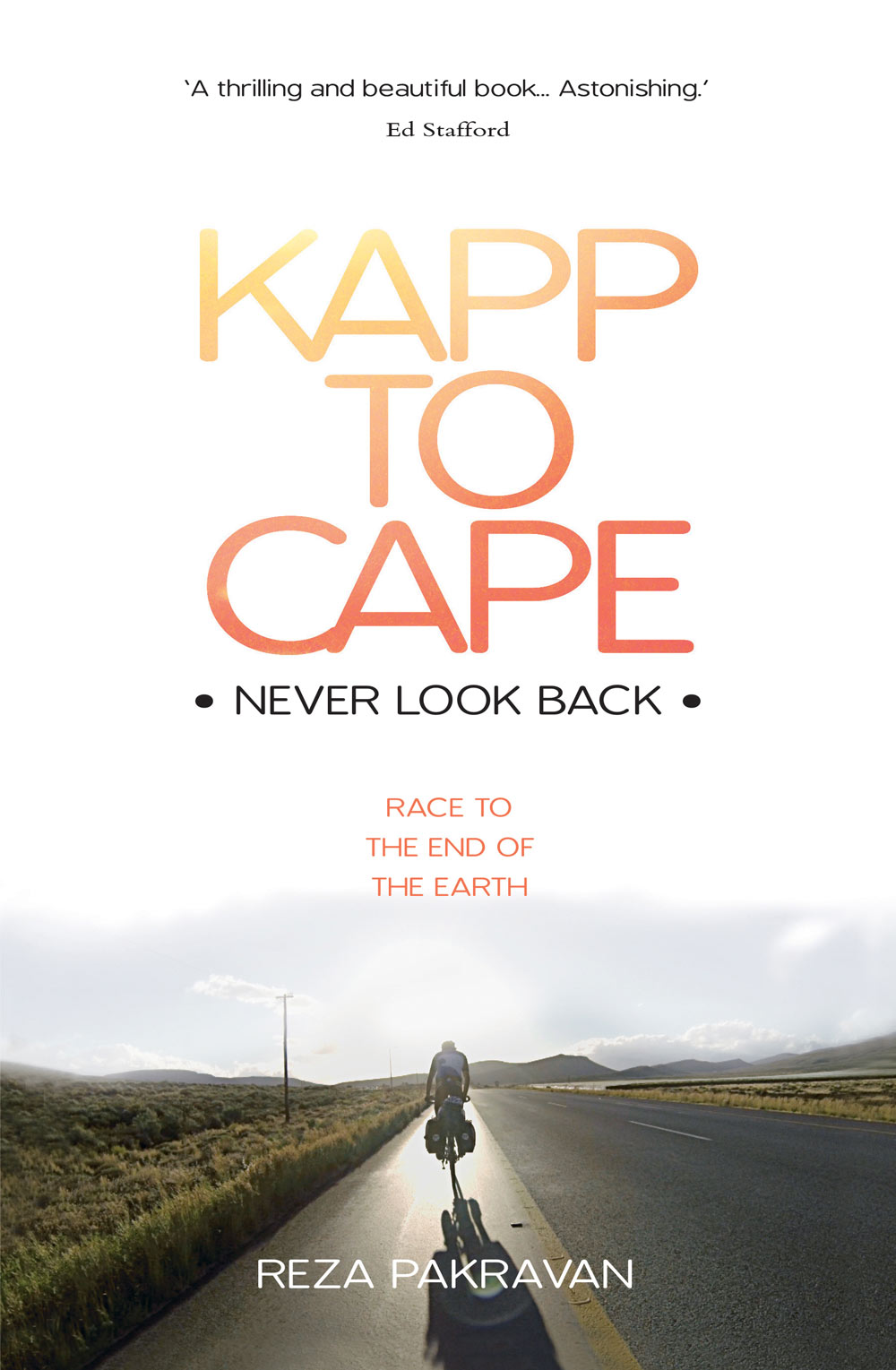

PRAISE FOR KAPP TO CAPE

'A thrilling and beautiful book. The journey that Reza undertakes both physically and mentally is astonishing.'

Ed Stafford, explorer

'A brilliantly candid, funny and thought-provoking escape to the wild. Through Reza's unique cultural lens we are taken on the adventure of a lifetime, and left reflecting on our own sense of purpose and adventure.'

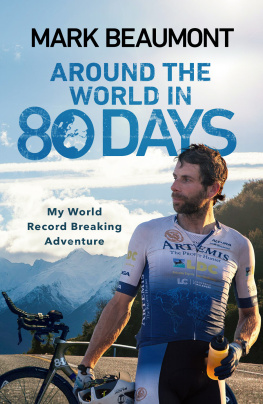

Mark Beaumont, author of The Man Who Cycled the World

'It took me over a year to cycle to South Africa. Reza managed it in just 100 days that is extraordinary.'

Alastair Humphreys, adventurer and author of Grand Adventures

'I am literally lost for words at the scale of this heroic achievement. To the benefit of his readers, Reza isn't.'

Tim Moore, author of Gironimo!, You Are Awful (But I Like You) and French Revolutions

'An absolute page-turner about Reza's courageous world-record bid. The inner journey is every bit as fascinating as the outer as he candidly shares his doubts, struggles, challenges and triumphs while navigating some of the world's most cyclist-unfriendly regions and roads. Recommended!'

Roz Savage, world-record ocean rower and author of Rowing the Atlantic

'A moment of self-realisation among the commuters on London Bridge triggers a selfless and enduring determination in Reza Pakravan, to live his own life in a way that makes a positive difference to others. Kapp to Cape is the story of an epic journey of self-discovery, self-discipline and triumph against all the odds. It reveals the best of the human spirit and reminds us, yet again, that a life well-lived is never about the destination: it's about the ride.'

Deborah Bull, CBE, dancer, writer and broadcaster

KAPP TO CAPE

Copyright Reza Pakravan, 2017

As told to Charlie Carroll

Plate section photos Reza Pakravan

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means, nor transmitted, nor translated into a machine language, without the written permission of the publishers.

Reza Pakravan and Charlie Carroll have asserted their right to be identified as authors of this work in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Condition of Sale

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Summersdale Publishers Ltd

46 West Street

Chichester

West Sussex

PO19 1RP

UK

www.summersdale.com

eISBN: 978-1-78685-100-0

Substantial discounts on bulk quantities of Summersdale books are available to corporations, professional associations and other organisations. For details contact general enquiries: telephone: +44 (0) 1243 771107, fax: +44 (0) 1243 786300 or email: .

To my Mum and Dad

CONTENTS

PART ONE

BEGINNING

CHAPTER 1

LONDON BRIDGE, FALLING DOWN

The revelation came at 8.45 a.m. one cold November morning. On London Bridge, beneath a canopy of low-hanging cloud, I stopped.

A man walked into my back. Others jostled on either side of me, shoulders connected with shoulders, elbows with elbows, and I was nudged and bounced in a chorus of grumbled complaints towards the railings. I clung to the concrete, standing firm, an immoveable object. The tide of commuters found its rhythm once more and flowed around me with no further contact, as if I was surrounded by some unseen bell curve of protection a sheen of impenetrability: the physical space we afford those we do not trust. I was no longer perceived as trustworthy on this bridge. I had broken the rules. At this time of day, you do not stop. Those who do are inconsiderate or inexperienced or, worse, mad. Perhaps my fellow commuters thought exactly that: I was mad and therefore best avoided. I did not mind so much.

I looked about me. Down below, the Thames boiled and chopped, its thick and silty swells smacking wetly against the bridge's legs. It flowed relentlessly and without mercy, the same colour as the bulging clouds above. As I turned and rested my back against concrete, it struck me that these people, this river of suits and umbrellas, matched the waters below. Leaden and dreary, they stopped for nothing. If I had fallen, if I had dropped to my hands and knees at that very moment, if I had crumpled and landed spreadeagled on my back, would anyone have stopped? Or would the tide have merely pushed around me, even over me, and continued on? Perhaps. And, if so, you can't blame it. It's what a river does.

The revelation was a simple one. I was a part of this river this surge of workers washing over London Bridge towards the City only to repeat the same in reverse 10 hours later and then continue the numbing exercise day in and day out and I had been for almost a decade. This had never been the plan.

Five months later, I found myself facing a different river. Unlike the Thames, which had flowed 30 ft beneath me from my London Bridge vantage point, this one was just a few centimetres away and all my energy was focused on keeping it from washing into my tent. Piling sacks of rice against the inside of the door flap and wrapping my scant belongings into plastic bags, I wedged my guitar against one of the bending tent poles as extra support and then lay on my back across the groundsheet, praying that my own weight would serve as ballast to keep the tent rooted to the muddy earth. The wind roared and howled outside as the tropical storm rose in pitch and intensity, whipping the thin canvas walls in and out.

The river was a new addition to a landscape I thought I had come to know. It had not been here yesterday. But the storm had raged mercilessly for hours now and, with nowhere to go, the rising rainwater had pushed up from the saturated earth and found its trajectory. My tent was still not quite in its path it had not yet suffered the same fate as the fallen branches and ripped-up roots that sailed past me on the churning, blood-red tumult but if the rain did not stop soon it, and all my belongings, would doubtless be swept away. I remained on my back, motionless, breathing slow and deep in contrast to the downpour that splattered against my tent in a deafening thunder. There was no sign that this storm would end. I had not been so happy in years.

The tent had been my home for the past two weeks: pitched in the small village of Agnena, deep in the heart of Madagascar. I was there as a volunteer labourer for a non-governmental organisation called SEED Madagascar, which built much-needed schools in rural areas of the country. The London Bridge revelation had left me hollow and bereft, desperate to find a way to bring a sense of purpose to my life, something noble through which I could prove to myself that I wasn't just a City-bound financial analyst contributing nothing to this world nor to myself. That desperation had led me here, to Madagascar, to this tent, to this storm.