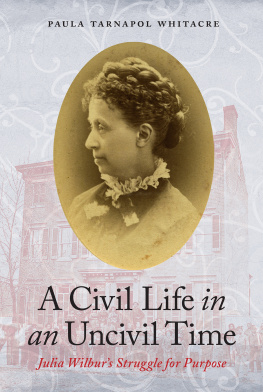

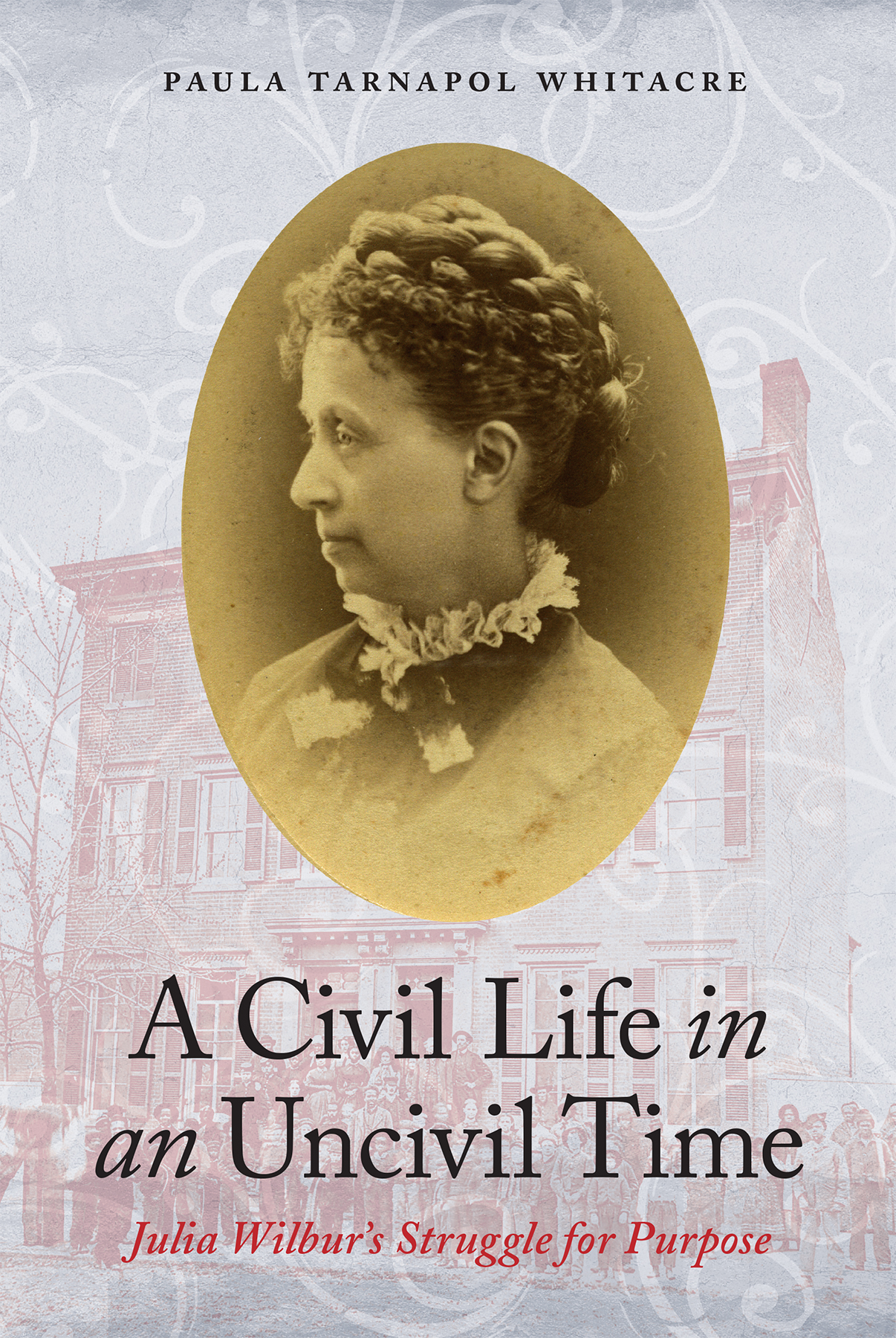

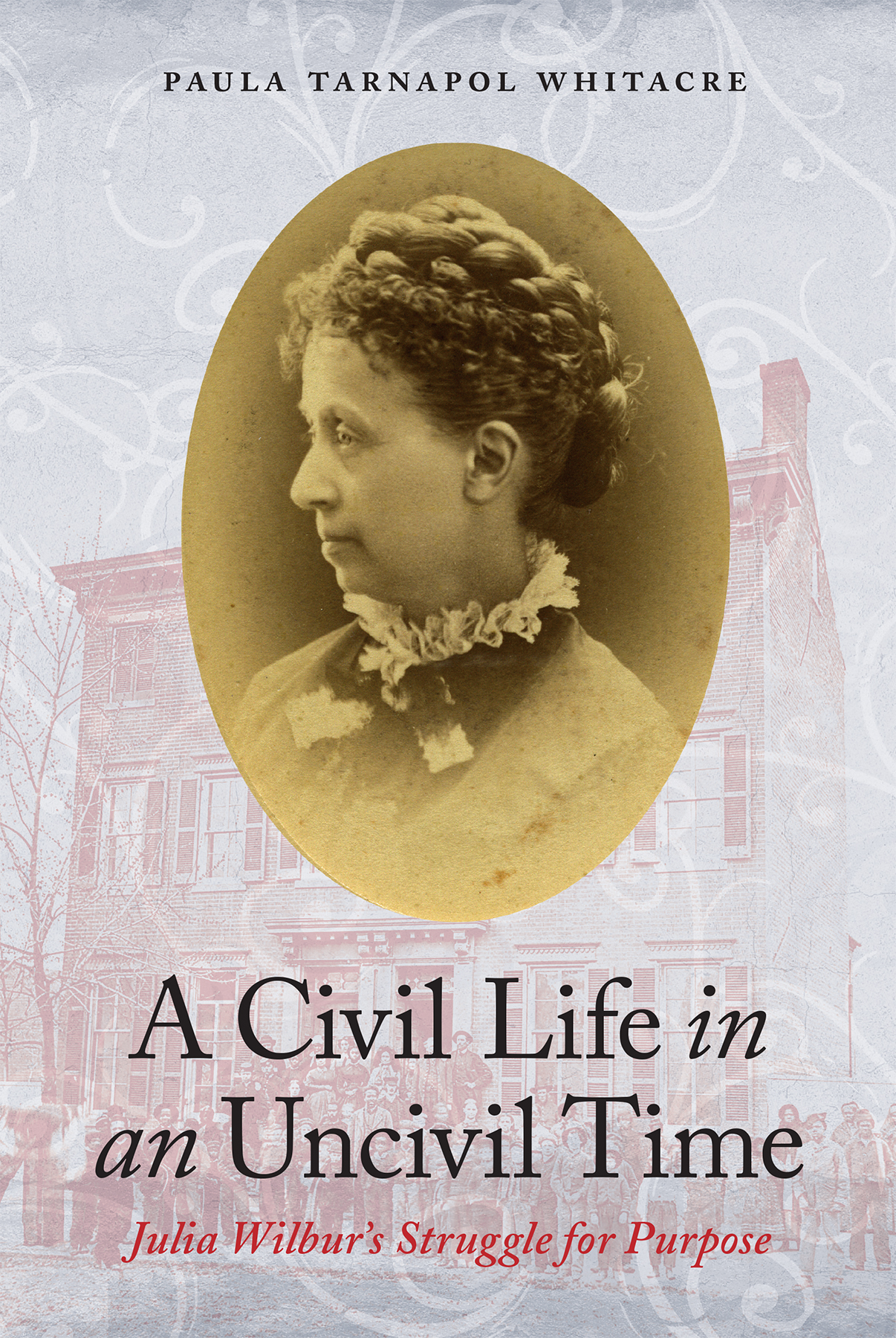

By illuminating Julia Wilburs struggles to end slavery, join the emancipated in the fight against bigotry, and live a life of purpose, Paula Whitacre offers a rich biography and beautifully written history.

Chandra Manning, author of Troubled Refuge: Struggling for Freedom in the Civil War

Paula Whitacre shines a light on a remarkable character, abolitionist Julia Wilbur, who... heroically confronted misogyny, racism, and fear in an effort to aid enslaved African Americans making the transition to freedom. Here this important and timely story is empathetically brought to life. I urge everyone to pick up a copy and delve deeper into a chapter of Civil War history that has been overlooked for far too long.

Lisa Wolfinger, co-creator and executive producer of the PBS series Mercy Street

Paula Whitacres biography captures the extraordinary life and times of this seemingly ordinary American woman.

Carol Faulkner, author of Lucretia Motts Heresy

Paula Whitacres scholarship expands our knowledge of the African American experience before, during, and after the Civil War. A fascinating look at Wilbur and Civil War Alexandria, Virginia.

Audrey P. Davis, director of the Alexandria Black History Museum and historical advisor to the PBS series Mercy Street

Paula Whitacre has created a compelling portrait of a nineteenth-century abolitionist working on the front line of change. Julia Wilbur joins the ranks of tough-minded women who stood firm at the point where idealism meets reality.

Pamela D. Toler, author of Heroines of Mercy Street

In resurrecting Julia Wilburs life, Paula Whitacre vividly conveys the struggles, both mundane and momentous, that reshaped families and nations in the Civil War era.

Nancy Hewitt, author of Radical Friends: The Activist Worlds of Amy Kirby Post, 18021889

In Paula Whitacres talented hands, Julia Wilburs life bursts from the page. She appears as an adoring aunt, an ardent activist, Harriet Jacobss ally, a committed teacher, and, most of all, an eyewitness to the ending of slavery and the beginning of freedom.

Jim Downs, author of Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction

A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time

A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time

Julia Wilburs Struggle for Purpose

Paula Tarnapol Whitacre

Potomac Books

An imprint of the University of Nebraska Press

2017 by Paula Tarnapol Whitacre

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover images are from the interior.

Author photo 2016 Lisa Damico Portraits.

All rights reserved. Potomac Books is an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017944081

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

For Bill, who believed from the start

Contents

People often ask me about how I found Julia Ann Wilbur and her diaries, which she kept in various forms from 1844 to 1895. We connected through Alexandria Archaeology, part of Alexandrias extensive local history program, in 2010, when I volunteered to research the more than thirty Union hospitals that sprang up during the Civil War. Among other sources, I consulted Julia Wilburs diaries on microfilm in the Alexandria Librarys Local History and Special Collections Room.

One thing led to anotherfirst I offered to transcribe the Civil War years of the diaries. Then I decided to learn what Julia Wilbur did right before the war to set the stage, then right after, then long before, etc. Finally, after peering at microfilm for a year or so, I visited the originals in the Quaker & Special Collections at Haverford College. Douglas Steererespected Quaker thinker and activist and Julias great-great-nephew (direct descendant of her youngest sister Mary)donated the diaries to the college, where he taught from 1928 to 1964.

At the time of my first visit to Haverford, Julia Wilburs papers lived in four gray boxes, about the size of shirt boxes (since transferred into six more neatly partitioned containers). I opened the first to find her pocket diaries, each a small, leather-bound volume. Nice. It was amazing to touch what I had only peered at through a microfilm machine. But I really jolted when I opened the next box. There sat several dozen packets of cream-colored stationary, about 5x7 inches in size, tied up with red ribbon, a parallel set of diaries that began in 1844 (more than ten years before the pocket diaries). In them she waxed on for many pages on one day, then wrote maybe just a line or two on the next. The collection ends abruptly in 1873, but in reading them and her other diaries, I assume later years got lost. Known to scholars and others who used the collection, these diaries surprised my colleagues in Alexandria and me.

But I had just spent two years transcribing the pocket diaries. If I tackled this second set, I would probably still be typing today. A solution emerged. Friends of Alexandria Archaeology, a nonprofit group, and Haverford split the cost of scanning and uploading the pages onto a dedicated website. About twenty-five volunteers in Alexandria each took seventy-five pages, often many more, to transcribe. As a result, we transcribed, proofread (albeit still with typos), and compiled more than 1,800 pages in just over a year.

I fulfilled my original goal: transcriptions of Julia Wilburs diaries are online and searchable through Alexandria Archaeology.

My goal grew, as this book attests. Beyond making individual diary entries available, I wanted to draw on them to tell Julia Wilburs story and the story of an amazing time in our nations history.

What would Julia Wilbur think about this endeavor? After working with the diaries for many years, I believe she knew she was preserving something special for posterityalthough probably did not envision posterity to encompass so many of us. We have Professor Steere to thank for transferring the diaries beyond the family confines.

As I dug into the pages, I wondered, however, if I violated her privacy, particularly her painful experiences in 1860 and 1861 related to losing custody and virtually all contact with her beloved niece Freda (see chapter 3). I think not. She reviewed her diaries many times over the years. Later in life she started extracting entries into another record, which she titled Journal Briefs. She easily could have taken out pages or crossed parts out in her look-backs. Moreover, she referred to thoughts deemed too personal or damning with cryptic comments along the lines of People have wronged me today. And she only alluded to events most scandalous for the time, such as her sister Francess marital difficulties. A few times, too, she wrote about rereading and destroying personal letters.

A note about the direct and indirect quotes in this book: all conversations, thoughts, and dreams attributed to Julia and others come from diaries, letters, or other source materials. I wrote out a few abbreviated words (such as cd. and wd. for could and would) to ease the reading and have added explanations in brackets. A few terms discomfort us today (such as colored), but I have maintained the original in all cases.

The Saddest Sound I Ever Heard

The church bells of Alexandria, Virginia, tolled the morning of Saturday, April 15, 1865, a strange time to ring even on Easter weekend. Julia Wilbur heard the news as soon as she woke up. President Lincoln was dead, shot in the head while at the theater. Of course, she didnt believe it.