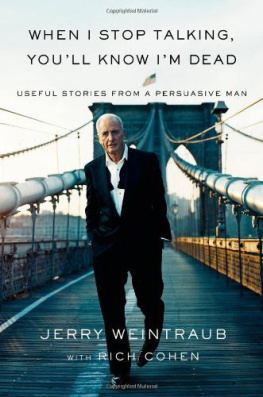

Like conferring with a Remington bronze. Steve McQueen and me on the set of Tom Horn . (The Fred Weintraub Collection.)

CHAPTER THREE

WANDERLUST

The first time I ran away from home, I was 12 years old. Like most hyperactive kids with a perfect older sibling, I was forever coming up short. My sister Lucille was always right; I was always wrong. Everything was my fault; nothing was hers. One day, in the aftermath of some petty verbal skirmish or lamp-breaking escapade, I took the heat as usual from my mother. But unlike the billion or so previous incidents, this time I was absolutely right, 100% blameless, and innocent beyond a shadow of a doubt. Oh, the injustice of it all!

Fired up by my righteous indignation, I cracked open my piggy bank, pocketed my life savings, and hit the road. I walked over to Bruckner Blvd., where a friendly trucker picked me up and headed north on Route 1, depositing me hours later in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Surprisingly, my life savings paid for only one night in a flea-bitten hotel room that was repulsive even by a 12-year-olds standards. The next morning I called my mother; but standing on my principles, I said I wouldnt come home until she apologized. Well talk about that when you get here. Im wiring you money for a bus ticket. Come home immediately. Not only did she not apologize when I got home, but my father sentenced me to the coal basement for a month of hard laborassembling Taylor Tot strollers (60 screws in each). I didnt even get my usual quarter for each one I put together. To this day, my wife cant understand why I react to screwdrivers the way Dracula reacts to a side order of garlic bread.

The second time I ran away from home, I was 26. By then the home was in tony Scarsdale, New York, and I left behind a wife, two young daughters, and the career I had dreamed of my whole life. Having gone into the family business fresh out of Wharton, I expanded the business from two stores to fifty, making it bigger and more successful than my father could ever have imagined.

***

By all outward appearances, I was the very model of a modern major general manager. I had a career, a promising future, and a family in the suburbs to go home to. I was living the 1950s version of the American Dream. All around me were satisfied businessmen, lawyers, doctors, and executives, all happy in the suburbs and proud of the work they were doing. Or so it seemed to me. Like the rest of them, I got up at 6 a.m. to hit the links, played gin with the neighbors, talked sports with the guys, even mowed my own lawn. If you had asked me then if I were content, I would have said, Sure, why wouldnt I be? But in truth, I was dying a slow, lingering death inside, and I couldnt put my finger on the cause. I didnt write the lyrics to the song Is That All There Is? made famous by Peggy Lee years later, but I could have. There had to be something more to life, something I was meant to do. But what that was, I had no idea. I just knew I wasnt happy.

My dissatisfactions came to a head when, despite my expanding Darling Furniture & Toys, my father still refused to give me a piece of the business, saying, When I die, youll get it all, but until then, youve got your job. I was seized by that same old righteous indignation that sparked my flight to Bridgeport. Oh, the injustice! Whats more, I was feeling restless and suffocated in a marriage entered into impulsively and at too young an age. My chronic shpilkes had become acute, and I felt the need to escape the American Dream that was choking me just as surely as the insidiously unstoppable suburban crabgrass was choking my front lawn.

One night in 1956, I saw Federico Fellinis masterpiece, La Strada. I was devastated by the final image of Anthony Quinn as the itinerant strongman, Zampan, emotionally shattered by the repercussions of his own brutality and selfishness, clawing at the sand in despair. He was the bad guy of the piece, but I felt his anguish and shared the certainty that, like Zampan, I would never amount to anything, never love or be loved. I was a basket case. To the utter shock of my friends and family, I did the unthinkable: I packed my bags and walked out the door.

When I take off, I take off. I left with nothing. My wife got the house, the kids, the crabgrass, and most of my money. I moved into a second-floor apartment in Gramercy Park. It was the first time I had ever had my own placeno parents, sisters, wives, children, or roommates. The feeling of freedom was exhilarating, but I had no idea what I was going to do with it. I had never known anything but the baby carriage and toy business and I thought I was never going to work again. So I did what all lost youth do. I went to Europe. I got there by answering an ad for staff positions on the ocean liner Ryndam. I was hired as a social director and was issued a cabin and a whistle. I didnt get any salary, but in exchange for leading games of Simon Sez and dancing with old ladies, I was given free passage and meals. The only thing I had to pay for was alcohol. Thank God I was never a big drinker.

I made my way to Paris, where I had the name of a friend of a friend. He introduced me to a talented black cabaret singer; I ended up moving in with her. I sure wasnt in Kansas anymore. We shacked up for a month or so until she got bored with my sexual inexperience, or tired of me not paying rent, or her boyfriend showed up. For whatever reason, she gave me the boot. Eventually, I made my way to the Holy Land, where I had been offered a job doing some sort of public relations work for an Israeli firm. When I realized that the only difference between being under the thumb of Israeli bosses instead of American bosses was that my paycheck would read from right to left, I headed home.

Deathly pale at my first wedding. The mic stand is the only thing holding me up. (The Fred Weintraub Collection.)

Madison Avenue

I had to go halfway around the world and back to get from The Bronx to Manhattan. I arrived in town with no job and no prospects, but I had a psychiatrist friend on the Upper East Side with an extra apartment behind his office. He let me use it while I got my act together, which I did with the help and encouragement of a true and gracious friend.

I first met Tom Murray in 1955, when I was still running the Darling baby carriage and toy stores. At the time, Tom was working as a freelance copywriter for Getschal Advertising, the agency handling my account; soon, we became great friends. Tom and his wife, Evelynalways willing to take in strayswere even kind enough to let me crash in their Greenwich Village apartment on Eighth Street whenever I was between homes. I wasnt their only itinerant houseguest at that time. They were also playing host to two noted musical performers: Annie Ross, the great jazz singer who had recorded with the Modern Jazz Quartet, and Georgia Brown, the singer and actress who would soon make a splash as Nancy in the original stage production of the musical Oliver.

An experienced adman, Tom recognized early on that I had a lot of creative ideas and a knack for promotions, and he lobbied hard to get Getschal to hire me. Four months after turning down a publicity and promotions job in Israel, I found myself doing exactly the same job in New York. The only difference was that I wasnt an employee of the company; I was a freelance consultant working directly with Budd Getschal, the head honcho. For him I created Good Neighbor Pharmacies and Friendly American Hardware & Housewares, two hugely successful retailers cooperatives made up of individually owned and operated stores sharing advertising costs. I was reborn as a Mad Man, and the work suited me for the time being. For one thing, it allowed me to vacate my temporary digs and take an apartment in Greenwich Village.

Next page