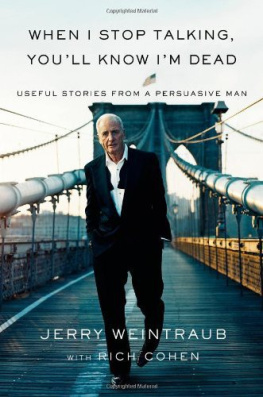

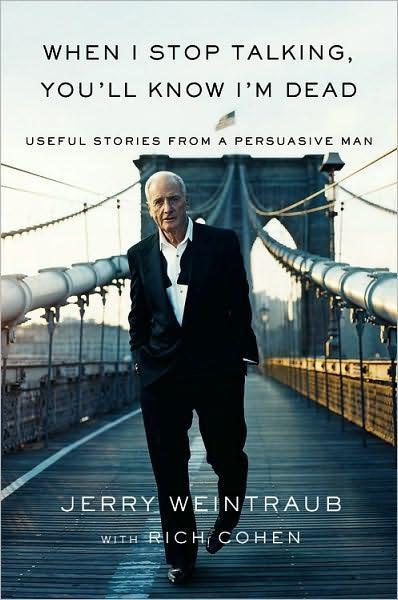

Jerry Weintraub, Rich Cohen

When I Stop Talking You'll Know I'm Dead

To Rose and Sam Weintraub,

without whom none of this

would have been possible, and

of course, Jane and Susie.

There once was a kid with a dream

Whose vision was clear and supreme

He formed Management Three

And quick as can be

The dream became one with his scheme

First there was Denver and eventually Frank

Followed by Dorothy & Neil

His Rep. it did grow

And as we all know

Others came wanting to deal

He was man of the year,

"The Wiz of the Biz,"

And accolades too many to count

The dream and the scheme

Turned to bread and to cream

Success it continued to mount

The end of this rhyme is near.

Weintraub is really a dear.

When he's needed most

No more gracious a host,

No more generous a man is there-

With much love and appreciation,

Bob Dylan

This book is not the story of my entire life, nor is it the catalogue of my every adventure. It is not meant to exhaust every era nor chronicle every detail. It is instead a tour of just those select moments of hilarity or epiphany-at home and in the office, in the bedroom, studio, and arena-that pushed me this way or that and gave my life direction. The crucial hours, that's what I am after. I also mean it as a chronicle and tribute to some of the great figures of my time, the few I influenced and the many who influenced me. I have been fortunate to have known more than a couple of great people and to have worked with more than a couple of great artists. The story of these people, men and women, is the story of my age, and I consider myself fortunate to have been born in the right nation with the right parents at the right moment. In short, this book, if it is working, should read less like a text than like a conversation, a late-night talk in which a man who likes to talk and happens to have been alive a long time and had his nose in everything tells you of the high points, the grand moments, and the stunning incidents when everything was sharp and clear. I sometimes think a person is a kind of memory machine. You collect, and sort, and remember, then you tell. Looking back-and telling is nothing but looking back-I have come away with a profound sense of humility. I suppose this comes from recognizing my life as a pattern, a cohesive collection of incidents whose author I cannot quite discern. In other words, the more I live, the more amazed I am by living. And maybe that's right. As G-D says in an old book, "What you have been given is yours to understand, but the rest belongs to me."

I have a philosophy of life, but I don't live by it and never could practice it. Now, at seventy-two, I realize every minute doing one thing is a minute not doing something else, every choice is another choice not made, another path grown over and lost. If asked my philosophy, it would be simply this: Savor life, don't press too hard, don't worry too much. Or as the old-timers say, "Enjoy." But, as I said, I never could live by this philosophy and was, in fact, out working, hustling, trading, scheming, and making a buck as soon as I was old enough to leave my parents' house.

When I was ten, Robert Mitchum was arrested in the coldwater flat across the street from our apartment in the Bronx. I remember Robert Mitchum as the husky, sleepy-eyed actor who played all those noirish roles that told you there was something not so squeaky clean in Bing Crosby's America, but Mitchum got those parts only after the arrest, in which he was caught in bed with two girls in the middle of the day smoking dope. No small scandal. In those days, merely staying in bed till 9:00 A.M. was considered suspicious. It would have been the end of his career if not for some genius movie producer who realized all that public disgust could be harnessed by repackaging the actor into a dark, interesting, complicated character.

When the story broke, the parents in my neighborhood went wild. The schanda! This matinee idol picks our block to engage in his immorality? The yentas went up and down the street, wailing. One of the mothers on Jerome Avenue grabbed me by the collar and said, "Jerry, you're the younger generation, an American boy, what do you think of this actor with his chippies and his Mexican cigarette?"

I smiled with my hand out, because I had just made a delivery and was waiting for a tip. "I'll never see another one of his movies," I told her. "He has shamed not just our neighborhood, but all of the Bronx."

Then, to tease her, I said, "And did you hear? He's Jewish!"

"No! It can't be, you're joking."

"No joke. My brother Melvyn says they pulled tefillin and a prayer book out of that dirty little room."

"Oh, God, I'm going to faint!"

"Not yet," I said, waving my hand. And the purse came out, followed by a few well-circulated nickels.

Of course, I wasn't really disgusted by Robert Mitchum's behavior. I was awed. What did I think? I applauded the man. In bed with two women in the middle of the day? That's the dream! That's Hollywood!

I was born in Brooklyn, raised in the Bronx. When people ask where I'm from, I always say Brooklyn, though I spent only my earliest years in the borough. Brooklyn because when you hear the Bronx you think baseball, vacant lots, tenement fires, whereas, when you hear Brooklyn, you think guys. In my oldest memories, I am on the street, with a roving pack of kids. We hung out beneath the Jerome Avenue El, where the shadows made complicated patterns. The sidewalks were lined with Irish and Italian bars. On my way to school, I would see the drunks at their stools, having their first shots of the day. We stayed out there for hours, talking about what we wanted. We played stickball and stoopball, the Spalding bounding off the third step of the brownstone, arcing against the beams of the elevated. When a train went by, it rained sparks. If you listened to us, you would not have understood half of it, everything being in nicknames, slang, and code. My brother Melvyn was (and is) my best friend, two years younger, not a resentful bone in his body, though he had to pay for my sins in school: Mel Weintraub? Jerry's brother? You sit in back and keep your mouth shut.

The neighborhood was bounded by big roads to the south and the Hudson River to the west, with a distant view of the Palisades. Manhattan was just a twenty-minute subway ride, but a light-year, away. At night, when the IRT train went over Jerome Avenue, its windows aglow, I dreamed of going to the city. I was impatient to see the world. Now and then, tired of gray days in the classroom, I cut school and instead caught a train to Times Square, where I sat through two features and a floor show at the Roxy or the Paramount or one of the other grand show palaces. The velvet curtains, the plush aisles, the stars and stage sets and glamour-this is where I fell in love with movies. Back to Bataan with Robert Taylor; Pursued with Robert Mitchum; Here Comes Mr. Jordan with Robert Montgomery; Fort Apache with John Wayne; The Beautiful Blonde from Bashful Bend with Betty Grable, with that body and those legs, each insured for a million dollars by Lloyd's of London. This was not a theater; it was a synagogue. Everything I wanted was up on the screen.

There is nothing better than coming out of a movie on a summer night when the sun is still in the sky. I would take the train back to 174th Street and wander through the neighborhood, past the Chinese laundry, druggist, newsstand, smoke shop, deli, with scenes from the movie flickering in my mind-gun battles, chases, immortal bits of dialogue. I'll get you, you dirty rat. I would toss off my coat as I came in the door, overwhelmed by the smells from the kitchen, where my mother was cooking one of her great Eastern European dishes. It gave me so much, just knowing she was back there, at home, worrying and waiting; a sense of security; a sense that the world has order, and will continue tomorrow as it is today.

Next page