For my family

Margie and Bill

Sara

Caden and Tallulah

Two roads diverged in a wood, and II

took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

The Road Not Taken

Robert Frost

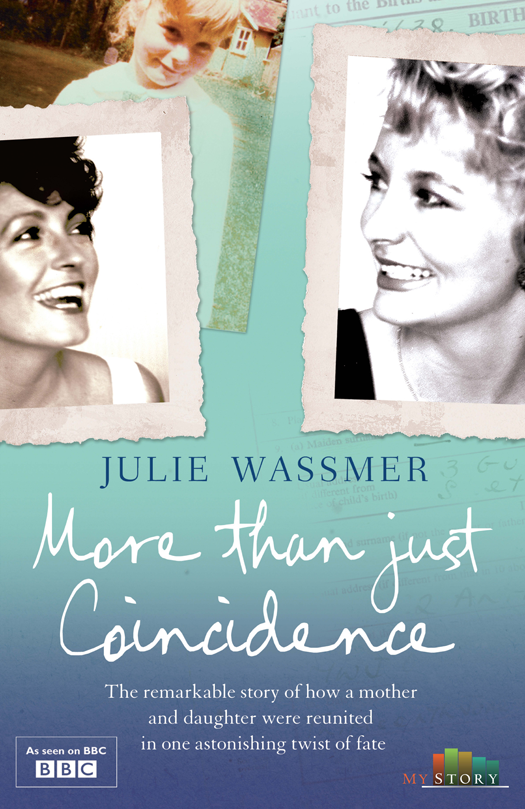

C lose to the sea, near my home, I have a small wooden beach hut, where I spend long summer days with my husband, daughter and grandchildren. It is also the place where I write. Sometimes there is little more to distract me than the cry of seagulls and the turning of the tide. Sitting on the verandah, looking out at the horizon, I have a sense of completeness and calm, of everything being just as it should be. It is a feeling that eluded me for so long. Wherever I went, and however happy I was, I knew that within me there was an empty space. I was sure that one day the missing piece would be restored, but until then my heart would never be quite whole.

As a television scriptwriter I have countless plotlines to my credit but still none so extraordinary as the drama I experienced in my own life almost twenty years ago: an apparent coincidence so remarkable that many people have been compelled to search for more complex explanations as to how it could have happened.

Certainly it is hard to believe that mere coincidence could have brought together the disparate strands of my life in such an astonishing way, or provided me with the signposts that led me, at a precise time, on a precise day5 November 1990to a door on a busy street near Londons Piccadilly. Even then I could so easily have turned away. But I didnt. And by crossing its threshold I came face to face with my long-lost daughterwithout either of us knowing who the other was.

Two decades have now passed since that meeting. The fireworks that followed when the truth was revealed are long over but the emotions that overwhelmed me then are still just as poignant as they continue to reverberate through my life. How can I possibly describe what it feels like to abandon a child to strangers in a blind leap of faith, believing that they would be better parents than I could ever be? How can I explain the profound sense of loss; the absence so great that it becomes a haunting presence? How can I define the lasting joy brought by a reunion that seemed so random and yet so well timed?

Some have attributed this event to synchronicity, some to serendipity; others have seen it as fate. On a hot summers day in 2010, as I gaze out from the verandah of my beach hut at my daughter, playing with her own two children at the waters edge, I know, as sure as my beating heart, that what drew me to her that day was more than just coincidence.

It is time to share my story.

Chapter One

Black Plimsolls Tied With Ribbon

I was an only child and likely to stay that way. My mother often remarked that, while she loved me dearly, she would have been just as happy with a litter of puppies. It was a sentiment that shocked friends and neighbours but I understood it completely: there were animal people and there were children people. My mother belonged in the first camp. For that matter, so did I.

At four years old I mothered my own familyhamster, tortoise and a tabby cat unimaginatively named Tiddles (I never knew an East End cat called anything else) who allowed me to dress him up in dolls clothes. I also trained our hen, Ada, to pick up washing in her beak from the laundry basket for me to peg on to the clothes line and rescued many a tiny sparrow, setting them carefully into cardboard boxes lined with cotton wool. Human babies, however, held no more fascination for me than they did for my mum.

While other mothers cooed over babies in prams, mine sat with me in the Rex picture house in Roman Road market, sobbing over the death of Shep or Old Yeller. When my father returned from work one evening to find us yet again red-eyed with grief (this time over Bambis mum), he insisted that enough was enough. From then on there would be only happy endings.

My mum, Margaret Mary Exley, always known as Margie, had had a tough childhood in Londons East End. One of five children whose father, a docker, had died of TB as a young man, she had left school at fourteen to help support her family. To her, work was not only a question of economic necessity but the key to self-reliance. She had given birth to me at the age of thirty-threeunusually late, in the 1950s, for a woman to be having her first childand a schoolfriend once commented to me how different she seemed from the other mums, most of whom had jobs in factories but dreamed of having enough money coming in to be able to stay at home with their children. My mum, on the other hand, had to be persuaded by my father to give up full-time employment to take care of me. She did so until I was four, but she couldnt wait to get back to work once I started infant school.

It was not as if she were a high-flying businesswoman with a fulfilling career. She worked as a waitress, on her feet all day, in a busy Kardomah coffee house on Kingsway in Holborn. But having known severe poverty growing up, she was in constant fear of sinking back into the kind of hand-to-mouth existence governed by pawnshops and tallymen. She seemed to live in a state of heightened reality, nerves strung taut, like a meerkat perpetually alert to danger. Yet at the same time she had a keen and tireless curiosity about other people, places and lifestyles that she could only glimpse in Hollywood films, and the coffee house, like the cinema, offered an escape from the daily grind of the East End. Every evening, she would come back with stale but exotic confections: sandwiches in rye bread, fruit croissants and Danish pastriesdelicacies never found at that time among the custard tarts and pork pies of an East End bakery.

Many of her customers worked nearby at Bush House, the headquarters of the BBC World Service, and she would proudly bring home autographed photographs of 1960s celebrities like the debonair newsreader Reggie Bosanquet, the actor Sam Kydd and even, rather surprisingly, strip-club owner Paul Raymond, the so-called King of Soho.

Years later, one night in 1978, the television news was headlined by the mysterious death of the Bulgarian dissident novelist and playwright Georgi Markov, believed to have been murdered with the tip of a poisoned umbrella. My mother was distraught. Markov, who had worked for the BBC World Service since being granted political asylum in 1969, had been not only her customer but also her friend, chatting with her every day over coffee and always leaving a good tip. She knew him as my Georgie. Its a wonder MI5 didnt take her in for background questioning.

My mother had been working at the Royal Mint at Tower Hill, swinging heavy bags of metal on to trucks, when she met my father, Bill Wassmer, a coiner who struck metal into money. Born in 1917, my dad was the eldest son of a soldier who had settled on Civvy Street as a baker. A dyed-in-the-wool trade union man, he was intelligent but for the most part self-educated. He became the long-term shop steward at the Mint, arguing his causes with considerable adversarial skill.

When they married in 1950 my parents put their names on the council housing list and moved into two upstairs rooms sublet to them by my fathers uncle and aunt while they waited for a home of their own. In my minds eye I can picture my father carrying their few possessions into their temporary accommodation at Lefevre Road whistling If I Knew You Were Comin Idve Baked a Cake, the cheery song popularised that year by Eileen Barton and Gracie Fields. Nearly twenty years later Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin supplied a grittier soundtrack to the timesand my parents were still waiting to be rehoused.