Contents

Guide

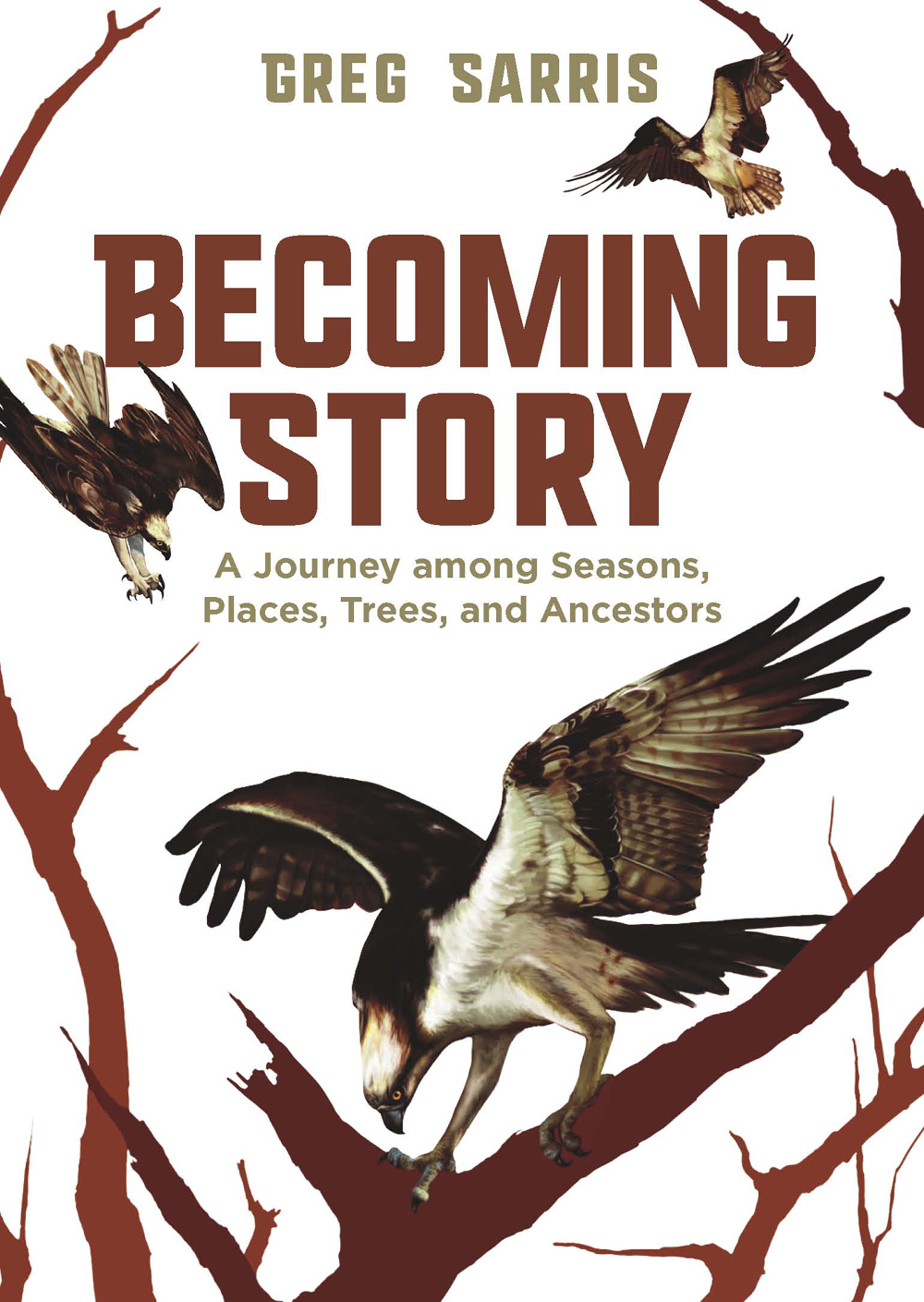

Copyright 2022 by Greg Sarris

All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from Heyday.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Sarris, Greg, author.

Title: Becoming story : a journey among seasons, places, trees, and ancestors / Greg Sarris.

Other titles: Journey among seasons, places, trees, and ancestors Description: Berkeley, California : Heyday, [2022]

Identifiers: LCCN 2021036078 (print) | LCCN 2021036079 (ebook) | ISBN 9781597145671 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781597145688 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Sarris, Greg. | Miwok Indians--California--Sonoma County--Biography. | Sonoma County (Calif.)--Biography. | Miwok

Indians--Folklore.

Classification: LCC E99.M69 S37 2022 (print) | LCC E99.M69 (ebook) | DDC 979.4/18--dc23/eng/20211020

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021036078

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021036079

Cover Art: Autumn Von Plinsky / www.autumnvonplinsky.com

Cover Design: Ashley Ingram and Autumn Von Plinsky

Interior Design/Typesetting: Ashley Ingram

Published by Heyday

P.O. Box 9145, Berkeley, California 94709

(510) 549-3564

heydaybooks.com

1 0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

SEASONS

FROST

Winter.

Not ancient stories about the time, before this one, when the animals were still people, before Coyote messed things up with his hapless machinations. Nor the dark room, warm but still black as the cold midwinter night outside, with nothing but the floating voice of the storyteller impersonating the people in the stories: crafty Coyotes devious whispering; Blue Jays shrill admonishments; Frogs old-man rasp; Quail, the most beautiful of all the people, her gentle-as-brookwater songs. None of those things. But cowsfeeding the cows, their cloven hooves planted in the frost-covered earth, nostrils blowing steam above an unfastened bale of alfalfa.

I would stand, warming my hands in my coat pockets, for hours watching the cows. I had a good eye then, not just for an old cows swollen knee, or maybe a rheumy eye, but even the faintest rise in her hide, indicating the presence of a grub. And the alfalfa, too: it was best if you could see dried purple flowers, sign of an early June harvest, after just enough warm weather. I was seven. I had no cows of my own but followed the local dairyman. I wanted a cow.

No Indians at home either. I was adopted. At the time, I knew nothing of my birth father, Emilio Hilario, or my Coast Miwok heritage. That would come twenty years down the road. And I would hear about the things the old-timers did. Winter activities; storytelling, for instance. Renowned Pomo basket weaver and doctor Mabel McKay, who I was fortunate to have known, explained the rules about the ancient-time stories: Only tell them in winter, after the first frost and before the last frost. Think about them then, their meanings. Not in summer, when theres snakes and things in the grass and you need to pay attention to where you are going. But that has nothing to do with memory, what surfaces from experience, as I recall winter now.

There was a man named Tommy Baca. He had only one arm, and he was a housepainter. My mother said a thousand times no one could mix color like Tommy Baca. He was a stocky man of medium height, with a broad, handsome face. He had thick, wavy black hair. He smiled a lot. I marveled at how he kept papers and such tucked against his side, just below his armpit, with the stub of his missing arm, and the way the stub would move, seemingly of its own volition, when he was excited, though I was careful not to let him find me looking. Dont stare at people, my mother snapped. He was Indian, Coast Miwok; if I knew as much then, I dont remember, and certainly not the Coast Miwok part. What interested me was that he had cows.

And because my parents were friends with him, I had access to the cows. They were steers, actually; mixed-blood dairy calves, Guernsey and Hereford, which in those days you could get for a drop in the bucket, as the dairy farmers kept only their purebred heifers. Out at Tommys place, west of town, I could spend hours with the critters. Once his son, Mark, about seven, like me, asked, Why do you always look at Dads cows? and I felt as if it was a bad thing, like when other kids called me adopted.

Im not clear about this next part. What happened exactly. Maybe because for a month or more I was on cloud nine. Did I hear my parents and Tommy Baca talking in the kitchen after work one night? Did I hear about it that way, before the afternoon out at Tommys when he said, Pick out the one you want. Take your pick?

A Guernsey and Hereford crossbreed steer. I kept him in the field adjacent my parents house. I named him Harry. Why I picked him from a lot of half a dozen others exactly like him, I dont know, or remember. He proved intelligent. He knew the time of day, precisely, when I arrived home from school, and never failed to stand just inside the aluminum gate always the same spotwaiting for me. He learned to genuflect, lowering himself on one knee, so that you could scratch the crown of his head and, later, when he grew, to make it easier to climb aboard his back. Yes, we rode himevery kid from the neighborhood in those days has a picture of himself or herself astride Harry.

His horns grew, but he was gentle, careful even, when he tossed his head to shoo flies or strew a flake of hay over the ground. Well, there was that one time, head lowered, when he charged Alan Chaney, chasing him out of the field. But no one cared since everyone knew Alan was a bully and had no doubt provoked Harry.

That was so long ago. A million stories ago. Of course, I found out who my father was, and now I can look back and understand things I hadnt the faintest idea of before. The connections between me and Tommy Baca, for instance. His grandmother, Maria Copa, sang for my great-great-grandfather, Tom Smith, the renowned last Coast Miwok medicine man, as he doctored the sick. I can imagine them along the coast and through inland valleys, traveling in a wagon and later in a Model T Ford. That box with the stuff of history spills the ancient villages fall out: Olumpali and Alaguali for Maria Copa, and Petaluma and Olemitcha for Tom Smith; then the Spanish galleons and English steamers, oceans crossed, wars, marriages, priests and soldiers, adobe and brick, overalls and Panama hats and, still, clamshell disc beads and flicker feathersand I see in that chance meeting of an adopted boy and a one-armed housepainter the miraculous web that is all of time, nothing more, nothing less, all-inclusive. But its memory that prevails still. Memory trounces this miraculous webthat is, if memory is not the vantage point from which I gaze upon it. No, not even Grandpa Toms songs left on wax cylinders, or his ancient-time stories left in a graduate students dissertation; not beads and feathers. Winter. Its feeding the cowsfeeding Harry. And frost. The earth is blanketed with frost. A quarter-inch thick at least, on the bare tree limbs, on rocks. Harry too is covered, topped as if with a layer of frosting. Harry steps into the sun to munch the alfalfa I just tossed over the fence, and I see the frost so cold, so powerful, begin to fall from his back, barely perceptible, trifling dust. And, again, Im not sure what happened exactlywhether I had overheard fattened and spring grass in a conversation between my parents and Tommy Baca the night before, or months before, and didnt understand, or chose not tobut at that moment I got it, understood the whole story, what the words would mean after the last frost, come summer. I might protest, but it would do no good. Never mind the purple blooms in the alfalfa. What a complicated and frightening world replaces winter.