The publisher gratefully acknowledges the support of the Dutch Foundation for Literature for the translation.

Ik denk zoveel aanjullie: Een briefwisselung tussen Nederland

en Duitsland, 19201949 1990 by Hedda Kalshoven-Brester

Originally published by Uitgeverij Contact, Amsterdam (1991)

English edition 2014 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014937797

ISBN 978-0-252-03830-3 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-252-07985-6 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-252-09617-4 (e-book)

PREFACE

Peter Fritzsche

The letters and diary entries that follow have profound things to say about the most brutal regime in the twentieth century. They are an indispensable source for understanding the Nazis. They shed light on the lives of individuals who lived in new, unexpected, and often terrifying times. A series of unlikely circumstances have made these sources available to contemporary readers.

One hundred years have passed since the youngest Germans who voted freely for the Nazis were born. In the meantime, more has been written about Adolf Hitler and his supporters, about the National Socialist movement they built up, about the world war the Nazis set in motion in 1939, and about the murder of the Jews they planned and implemented than about almost any other topic in history. To this day, we continue to fold this succession of terrible events over and over again. Indeed, in his book The Writing of the Disaster, the French philosopher Maurice Blanchot refers to the Holocaust and, behind it, the strong-armed movement of perpetrators, the mute responses of observers, and the bewilderment and final silence of victims, as the absolute event of history, when all history took fire, when the movement of Meaning was swallowed up. This utter-burn of eventsthe word choice indicates the difficulty of descriptionis indelible but also datable. The events seize us, but what historians do not agree on is their meaning: the reasons why the Nazis garnered so much support among German citizens before the seizure of power in 1933 or the evolving nature of that support in the Third Reich and through the war years. Scholars continue to debate the extent to which Germans were fundamentally attracted to the revolutionary and specifically racial aspects of National Socialism and the extent to which Germans approved of the persecution of their Jewish neighbors. Was Nazism a meaningful part of people's lives, or did Germans approach the regime in a more opportunistic, adaptive manner, and in what ways did citizens feel terrorized or ebullient as they participated in the course of events? Questions about the racial mindedness of ordinary Germans in the Third Reich and thus about the political malleability of lives in the twentieth century persist. Nazism poses fundamental questions about how people act as political beingshow they converge to make ideological commitments, how they respond to crisis and catastrophe, and how they understand power, entitlement, and injustice. The disasters of war and revolution in the twentieth century also indicate how little people actually see and how attenuated is their capacity for empathy. The events remind us that experience is always warped by expectation. For all these reasons, the attempt to understand the phenomenon of Nazism remains a compelling task.

We can't go back and interview Germans in the 1930s or 1940s about the Nazis or about the violence they saw around them or the complicity they might have shared. But thanks to an extraordinary cache of one family's letters and diaries that encompass the entire period from the end of World War I to the aftermath of World War II we can come close to hearing the discussions and debates that a handful of people had about the rise and the rule of the Nazis. We can take some provisional measure of how politics and war embedded themselves in everyday life. The German Gebenslebens and the Dutch Bresters trade impressions of Hitler, tell jokes on Jews, prepare racial passports, and worry about their men in the war. What has now come to be understood as the Holocaust is just visible on the margins, evident in a remark about the murder of Jews in Kiev and in a few diary notations about Eddy, a Jew in hiding. The letters and diaries create a convoluted, but quite open space in which we gain sight of the members of one German-Dutch family moving about, creating intimacy, keeping distance, and trying to understand on-rushing events. We can make some sense of the small, but consequential ways in which they made history, although perhaps not quite as they wished. This astonishing set of ego documents introduces readers in an unprecedented way to real fleshed-out protagonists in the precarious setting of revolution, war, and genocide.

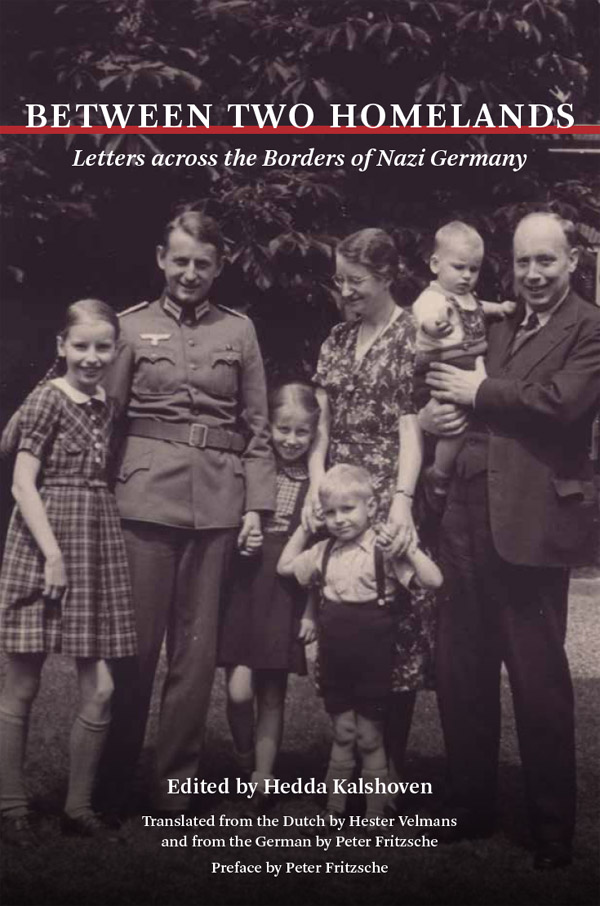

The spaciousness of the overall testimony is the result of several highly unusual factors. In the first place, the letters pull together a group of correspondents over four generations, extending down to Hedda Kalshoven (born Brester), the editor of this collection, who belongs to the last generation to have experienced and remembered World War II. The principal cast includes the great-grandmother, Minna von Alten (18591940), her daughter Elisabeth (18831937) and Elisabeth's husband, Karl Gebensleben (18711936), and their two children, Irmgard or Immo (19061993)Hedda's motherand Eberhard (19101944), Hedda's uncle, who was killed in the war. The correspondents also include a cousin, Minna von Alten's other granddaughter, Ursula Meier (19121986), Irmgard's husband August Brester (19001984), and her father-in-law Jan (18601934), as well as friends of Immo and Eberhard, particularly Carl-Heinz Zeitler, an outspoken opponent of the Nazis. The second reason for the spaciousness of testimony is the long time period during which the correspondents communicated: this selection of letters begins in 1920 and ends in 1949, from Immo's first trip to Holland after the First World War to her first return visit to Germany after the second. It is rare for a collection of letters, augmented by diary entries, to stretch across such a long time period. But the main reason for the spaciousness of testimony is that the correspondence crossed the boundary of Germany and Holland. After Immo married August Brester in 1929, she made for herself a new home in the Netherlands. The separation from her German family created contrasts between old and new, between the nationalist milieu in which Immo had grown up and the more liberal surroundings to which she moved. Immo and her mother, especially, tried to explain themselves to each other, a commitment that generated much more commentary about political events than is usually the case in family letters. What is extraordinary about this set of documents is the deliberate interest in explaining motives, particularly about National Socialism, which Elisabeth venerated. The difference in perspective sharpened when Germany invaded Holland in 1940 because Immo was forced to regard her own brother, Eberhard, an officer in the Wehrmacht, as one of the invaders of her new home. However, feelings of mutual affection and the desire for contact, especially after the birth of Immo's four children in the 1930s, constantly brought the German and the Dutch sides of the family together. The correspondence in this volume is thus shaped both by geographical and political difference and by personal intimacy. The deaths of Immo's parents in 1936 and 1937 and of her grandmother in 1940 also bound Immo and her brother more closely together despite their different perspectives on the war. The value of these documents is so great because they bring to voice a fairly large number of people across a long time period who are inclined by the circumstances of emigration and war to draw attention to what divides them as much as what brings them together.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.