Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

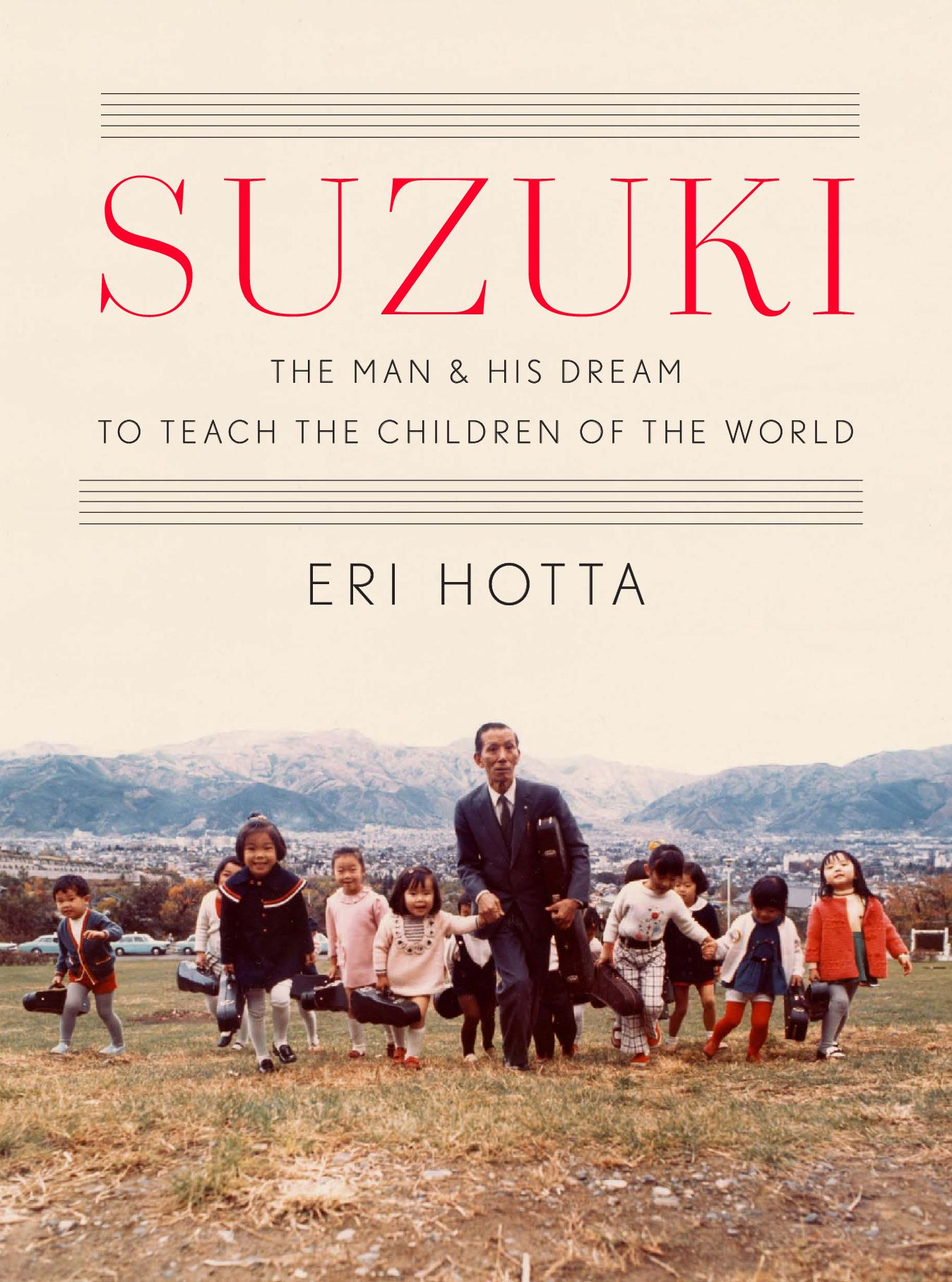

SUZUKI

The Man and His Dream to Teach the Children of the World

ERI HOTTA

THE BELKNAP PRESS

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

LONDON, ENGLAND

2022

Copyright 2022 by Eri Hotta

All rights reserved

Cover photograph: Talent Education Research Institute

Cover design: Gabriele Wilson

978-0-674-23823-7 (cloth)

978-0-674-27995-7 (PDF)

978-0-674-27996-4 (EPUB)

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE PRINTED EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

Names: Hotta, Eri, 1971 author.

Title: Suzuki : the man and his dream to teach the children of the world / Eri Hotta.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022009252

Subjects: LCSH: Suzuki, Shinichi, 18981998. | Violin teachersJapan. | ViolinInstruction and studyJapanJuvenileHistory20th century. | ViolinInstruction and studyJuvenileHistory20th century. | Humanism in music.

Classification: LCC ML423.S96 H67 2022 | DDC 787.2092dc23 / eng / 20220314

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022009252

For Ian

Contents

BORN IN 1898, Shinichi Suzuki lived through almost the entirety of the twentieth century. When he died, in 1998, the violinist, teacher, and humanist was best known as the founder of the hugely popular approach to early music education commonly known as the Suzuki Method.

According to the Talent Education Research Institute, an organization Suzuki founded in 1948, about 400,000 children around the globe are today learning to play music the Suzuki way. Particularly in the United States, where it was introduced in the late 1950s, the method has become synonymous with the musical education of preschoolers and school-aged children. Suzukis influence has been so pervasive for so long that, today, the great majority of people who were very young when they picked up a violinor cello, viola, piano, or flutehave likely come across his instructional approach in one form or another. Among top musicians who proclaim their Suzuki beginnings are violinists Kyoko Takezawa, Arabella Steinbacher, and Ray Chen. Many others, including Leila Josefowicz, Stefan Jackiw, Joshua Bell, and Hilary Hahn, had less thorough involvement with the Suzuki Method but were exposed to aspects of it in their early years. In 2020, Hahn became the third American violinist to record the repertoire accompanying the international edition of Suzukis method books, following David Nadien and William Preucil.

Yet Suzukis program was not intended to create professional musicians. His true goal, one that he maintained throughout his long career, was one of social transformation. He believed that the ills of his community stemmed from adults failure to help children fully realize their potential and thereby become enlightened individuals. And by children, he meant all childrenwhether their potential was great or small, whether it lay in music, mathematics, poetry, or athletics. This method is not education of the violin, he told a New York Times reporter in 1977. It is education by the violin. To Suzuki, the achievement of a certain level of mastery on the violin was only an examplealbeit a powerful oneof what any and all children could accomplish with proper guidance from an early age.

Notwithstanding his success in motivating families across the globe to put kiddy-sized violins in the hands of their children, Suzukis grand vision to redefine education remains little known. The primary reason for this neglect is that the Suzuki Method appears to work as a way of music instruction, and it is this, not the refashioning of society, that parents are looking for. Questioning the deeper meaning of education, and the state of existing educational systems, is not a task that most parents, guardians, and even instructors are prepared to take on when children sign up for music lessons.

For me, a historian and a mother who at one point projected her faith in the Suzuki Method onto her daughter, that is far from satisfying. Suzukis ninety-nine-year life, and the ideas he developed, encompass too much to overlook. His work took him from his birthplace in Nagoyawhere Japans turn-of-the-century innovators and entrepreneurs, including his father, thrivedto the culturally resplendent interwar Berlin of the 1920s, where he studied. Eventually he found himself in Tokyo on the eve of the Pacific War, where he started teaching young children. Next came the scenic alpine city of Matsumoto in Nagano Prefecture, where he opened a music school after the war. Then came celebrity, as Suzuki toured the world from the mid-1960s onward, well into his nineties. His journey through these historical landscapes raises questions both specific and broad about the evolution of his educational philosophy and about what music and learning are supposed to mean in our own and our childrens lives. What led Suzuki, who had no children of his own, to develop his approach? What propelled him to promote it with such passion? And in turn, why did his approach appeal so strongly to parents and educators both at home and outside his native Japan? To what extent was his larger educational philosophy, beyond the teaching and learning of music, acceptedor not?

Suzukis life was a quintessentially twentieth-century phenomenon, embedded within many of its historical turning points. They include the two world wars, the Cold War, and the cultural and economic globalization that continue to shape our world. The twentieth century was, as historian Eric Hobsbawm put it, an age of extremes, a time when opposing ideas and dogmas competed on a global scale to fundamentally change how people thought and lived. Exponents of influential ideologiesfrom socialism to internationalism, capitalism, and their countless variantspressed their visions of a good society. Befitting the zeitgeist, Suzuki pressed his own. He was first and foremost a revolutionary, striving to create a world where all children could thrive because this world would be more just and humane than the one he knew. He believed that better lives for all could be achieved by changing the way we bring up our children and therefore insisted that his was not merely an educational movement but also a social movement.

Central to Suzukis revolution was his conviction that talent is not an innate property, exclusive to those born with it. Rather, Suzuki contended that all children could claim talent, and he aimed to prove it. Moreover, he believed that not just his philosophy but also his pedagogical approach could be applied to all kinds of learning, so that every childs talent could be nurturedso that all the children around the world shine like little stars.

Suzuki advanced his project with unwavering confidence, which may explain the guru-like aura he exudes in the eyes of some of his methods followers. The pseudo-religious reverence of Suzukis most dedicated acolytes has, I suspect, shaped much of the existing literature on his life. My aim for this book is not to put the man in a pantheon but to show him and his legacies in expansive perspective. Suzukis life will also, I hope, serve as a lens through which we can see a panorama of cultural, artistic, and political shifts that marked his century. Perhaps, too, Suzukis story will help us, living in the twenty-first century, better understand ourselves.

If Shinichi Suzuki was a revolutionary fighter, bent on changing the worldand not just the field of musicthrough his educational approach, what, exactly, did he try to change? First and foremost, he sought to change the way talent is understood. This was the obsession that inspired, energized, and organized his work, which he called talent education (