Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

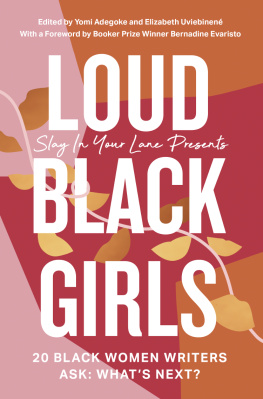

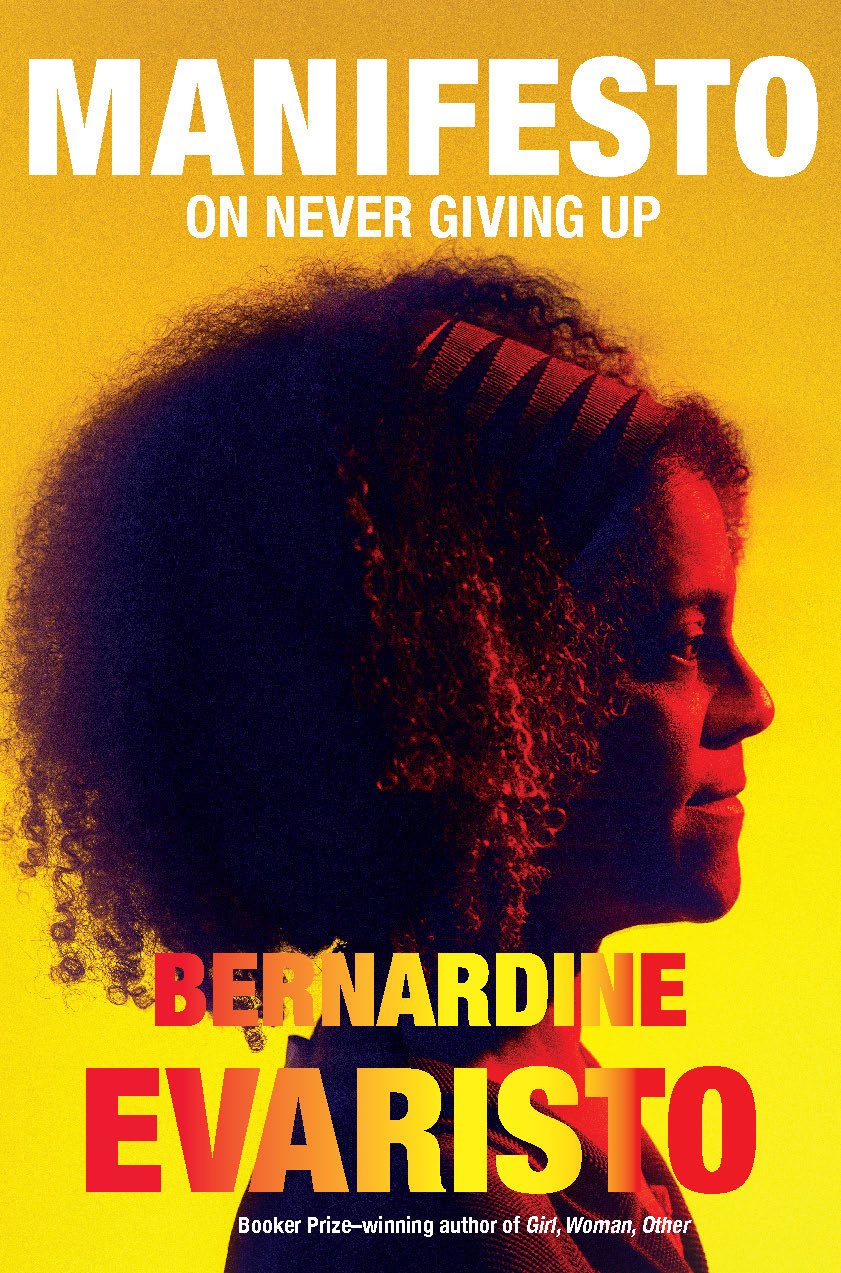

Also by Bernardine Evaristo

Island of Abraham

Lara

The Emperors Babe

Soul Tourists

Blonde Roots

Hello Mum (Quick Reads)

Mr Loverman

Girl, Woman, Other

MANIFESTO

ON NEVER GIVING UP

BERNARDINE

EVARISTO

Grove Press

New York

Copyright 2021 by Bernardine Evaristo

Jacket design by Gretchen Mergenthaler

Jacket photograph Stuart Simpson/Penguin Random House

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY10011 or .

Adinkra symbol supplied by www.adinkra.org

Epigraph quotation on from the film Gattaca by Andrew Niccol (Columbia Pictures)

Photograph of Bernardine Evaristo and Margaret Atwood, 14 October, 2019, reproduced by kind permission of The Booker Prizes.

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Hamish Hamilton, an imprint of Penguin Random House UK

First Grove Atlantic edition: January 2022

Published simultaneously in Canada

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available for this title.

ISBN 978-0-8021-5890-1

eISBN 978-0-8021-5891-8

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

For Simon Prosser, my editor and publisher since 1999, who has never accepted less than my very best, who stuck by me when it didnt make financial sense, who never asked me to tone it down or become more conventional with my writing and who always provided a home for my risky books. My Booker win was also his. Gratitude.

I never saved anything for the swim back.

From the film Gattaca by Andrew Niccol

Contents

Introduction

When I won the Booker Prize in 2019 for my novel Girl, Woman, Other, I became an overnight success after forty years working professionally in the arts. My career hadnt been without its achievements and recognition, but I wasnt widely known. The novel became a #1 bestseller sold in many foreign languages and received the kind of attention I had long desired for my work. In countless interviews, I found myself discussing my route to reaching this high point after so long. I said I felt unstoppable, because it struck me that I had been just this, ever since I left my family home at eighteen to make my own way in the world.

I reflected that my creativity could be traced back to my early years, cultural background and the influences that have shaped my life. Most people in the arts have role models writers, artists, creatives who have inspired them, but what are the other elements that lay the foundations for our creativity and steer the direction of our careers? This book is my answer to this question for myself, offering insights into my heritage and childhood, my lifestyle and relationships, the origins and nature of my creativity, and my personal development strategies and activism.

For those who have only encountered my writing at this newly elevated point of arrival, this book reveals what it took to keep going and growing; and for those who have been struggling for a long time, who might recognize their stories in mine, I hope you find it inspirational as you travel along your own paths towards achieving your ambitions.

So here it is Manifesto: On Never Giving Up: a memoir and a meditation on my life.

One

n (Old English)

ni (Yoruba)

a haon (Irish)

ein (German)

um (Portuguese)

heritage, childhood, family, origins

As a race, the human one, we all carry our histories of ancestry within us, and I am curious as to how mine helped determine the person and writer I became. I know that I come from generations of people who migrated from one country to another in order to make a better life for themselves, people who married across the artificial constructions of borders and the manmade barriers of culture and race.

My English mother met my Nigerian father at a Commonwealth dance in central London in 1954. She was studying to be a teacher at a Catholic teacher-training college run by nuns in Kensington; he was training to be a welder. They married and had eight children in ten years. Growing up, I was labelled half-caste, the term for bi-racial people at that time. Like all these categories Negro, coloured, black, mixed-race, bi-racial, of colour they function as accepted descriptors until they are replaced. We now understand that race doesnt actually exist it is not a biological fact and humans share all but 1 per cent of our DNA. Our differences are not scientific but due to other factors such as the environment. But race is a lived experience, therefore it is enormously consequential. Understanding the fiction of race doesnt mean that we can dispense with the categories, not yet.

The concept of black British was considered a contradiction in terms during my childhood. Brits didnt recognize people of colour as fellow citizens, and they in turn often aligned themselves with their countries of origin. I never had a choice but to consider myself British. This was the country of my birth, my life, even if it was made clear to me that I didnt really belong because I wasnt white. Yet Nigeria was a faraway concept, a country where my father had originated, about which I knew nothing.

I know a lot more about my mothers side of the family than I do my fathers. Not so long ago I discovered that my roots in Britain stretch back over three hundred years to 1703. It would have been helpful to know this as a child because I would have had a stronger sense of belonging, and it would have provided me with ammunition against those who told me, and every other person of colour of the time, to go back to where we came from.

Its not that one has to have British roots to belong here, and the notion that you only belong if you do should always be challenged. The rights of citizenship are not restricted to birth rights, and the water has always been muddied by those who were considered subjects of the British Empire, but who were not anointed with citizenship.

I know that DNA testing is controversial, as different services produce varying results based on their research pools, but I nonetheless find it fascinating. My Ancestry DNA test, which goes back eight generations, reveals an ethnicity estimate that describes my roots thus: Nigeria: 38 per cent; Togo: 12 per cent; England, north-western Europe: 25 per cent; Scotland: 14 per cent; Ireland: 7 per cent; Norway: 4 per cent. (The two countries I cant tie in with known ancestors are Scotland and Norway.)