About the Author

Barbara Blake Hannah is a Jamaican author, journalist, film-maker and cultural consultant. She trained as a journalist, then emigrated to London and worked as a PR executive for the Jamaica Tourist Board and government. She became the first Black TV journalist in the UK in 1968, starring in TV programmes Today with Eamonn Andrews and ATV Today, and working as a producer on BBC TVs Man Alive.

In 1972 Blake Hannah returned to Jamaica as a PR officer for the first Jamaican film The Harder They Come, and continued writing articles and books, becoming a Rastafari and articulate campaigner for acceptance of the religion. In 1984 she was appointed an Independent Opposition Senator, the first Rastafari to sit in the Jamaican Parliament. In 2001, she served as a member of the Jamaican delegation to the UN World Conference Against Racism (WCAR) in Durban, South Africa, where she was appointed a member of the special plenary on reparations, after which she established the Jamaica Reparations Movement that led to the establishment of the governments Parliamentary Commission on Reparations (2008). She presently serves as Cultural Liaison to the Jamaican Minister of Culture, Gender, Entertainment and Sport, and continues to work in the film industry.

Barbara Blake Hannah

GROWING OUT

Black Hair and Black Pride in the Swinging Sixties

With a New Introduction by

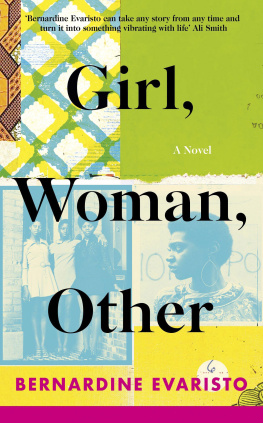

Bernardine Evaristo

PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published by Jamaica Media Productions Ltd 2016

First published with a new introduction by Penguin Books 2022

Text copyright Barbara Blake Hannah, 2016

Introduction copyright Bernardine Evaristo, 2022

The moral right of the copyright holders has been asserted

Cover art by Azarra Amoy

Cover photograph Edwin Sampson/ANL/Shutterstock

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologizes for any errors or omissions and would be grateful to be notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future editions of this book.

ISBN: 978-0-241-99377-4

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Livicated to Amy Jacques Garvey

Publishers Note

In this book are some expressions and depictions of prejudices that were commonplace at the time it was written. We are printing them in the book as it was originally published because to make changes would be the same as pretending these prejudices never existed, and that the author didnt experience them.

Introduction

For many people the Swinging Sixties was a myth predicated solely on the charmed young rock stars, artists, actors, errant debutants and models who sashayed down the Kings Road and Carnaby Street, and made headlines with their wild antics. Or at least thats what I thought until I read Barbara Blake Hannahs memoir, Growing Out: Black Hair and Black Pride in the Swinging Sixties, a gorgeously exuberant account of her decade living it up in London as a young woman.

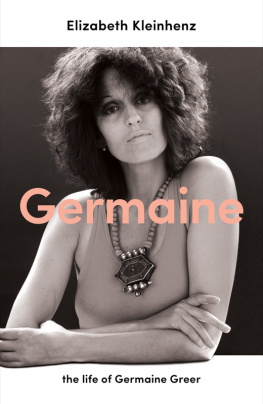

A middle-class journalist back home in Jamaica, when the opportunity arose for her to travel to England as part of a film in which shed been given a minor role, she jumped at it. Single, confident, carefree and ambitious, she was soon moving in aristocratic and artistic circles, among people who wanted to change the world. The young creatives of her acquaintance probably had no idea what the future held for them: the Australian Germaine Greer soon became Britains leading feminist writer; Richard Eyre would one day become the Director of the Royal National Theatre; and the film-makers James Ivory and Ismail Merchant were then at the start of their legendary Merchant Ivory Productions.

Parties, politics, nightclubs, restaurants, concerts, films, openings Blake Hannah made sure she was at the centre of the happening scene, aware of her exotic status as a black woman and the fashionable kudos she conferred on her white suitors when she walked into rooms draped on their arms. Living in rented accommodation, sometimes sharing, sometimes on her own, she spent many years ensconced in a garret right in the heart of Londons West End.

While Blake Hannah couldnt avoid the pervasive discrimination faced by people of colour, including an awful strip-search as soon as she landed from Jamaica, its interesting to read about her disconnect from the majority of Caribbean people who, at that time, struggling to make their way in the not very maternal Motherland, were far too preoccupied with cultural adjustment and survival to be swept up in the waves of a cultural revolution. When she first encounters the run-down city districts like Ladbroke Grove, where most of them lived, she describes their loose, threadbare suits, heads covered by narrow-brimmed hats, feet shod in broken-down shoes all wearing an air of suffering or sadness, of total dejection. The class and lifestyle divide is never more apparent and her gaze on her fellow immigrants makes stark the difference between the now well-recorded Windrush era narrative of struggle and her own rather more glamorous sojourn as a girl about town.

Blake Hannah is clearly beautiful, and we get a strong sense of her lively and engaged personality. Her conversational writing tone feels as natural and vivacious as if she were sitting opposite you chatting. Through a high-society friend she found secretarial and eventually other white-collar jobs, and she wrote features for major publications such as the Sunday Times and Cosmopolitan, before, amazingly, becoming Britains first black television journalist at the ripe old age of twenty-five.

When Thames Television recruited Blake Hannah as a reporter for their early evening news and magazine programme, headed by Eamonn Andrews, who went on to become a famous figure in British broadcasting, her appointment made the papers and turned her into a celebrity, but it also rankled with the outraged racists who crawled out of their slimy sewer pipes and wrote ceaseless letters of complaint to her bosses. Nonetheless, for a brief period she was sent on assignments nationwide, interviewing among others Prime Minister Harold Wilson and the actor Michael Caine, but a mere nine months in her bosses shamefully bowed to pressure and she lost her job. A second television gig ended in the same way.

Blake Hannah writes about this past with stoicism, but reading about her experiences reminds us how hard it was for her generation to make their way all those years ago when raw racism bottom-up, top-down was such a barrier to achievement. We can trace the paucity of representation of marginalized communities in so many fields today back to these earlier roots of systemic discrimination. This talented young woman who was bright, personable, aspirational, capable and willing could have had a long career in television, perhaps ascending to the heights of top commissioning and directorial positions, but instead her career was crudely, heartlessly and unjustly chopped off at the knees.