CONTENTS

| PREFACE |

| Chapter I |

| Chapter II |

| Chapter III |

| Chapter IV |

| Chapter V |

| Chapter VI |

| Chapter VII |

| Chapter VIII |

| Chapter IX |

| Chapter X |

| Chapter XI |

| Chapter XII |

| Chapter XIII |

| Chapter XIV |

| Chapter XV |

| INDEX |

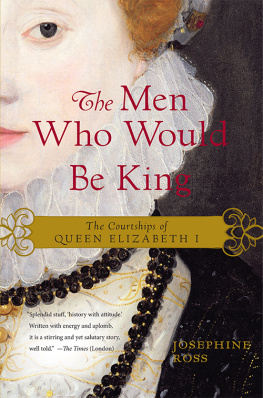

THE COURTSHIPS OF QUEEN ELIZABETH

ER Monogram

W.L. Colls. Ph. Sc.

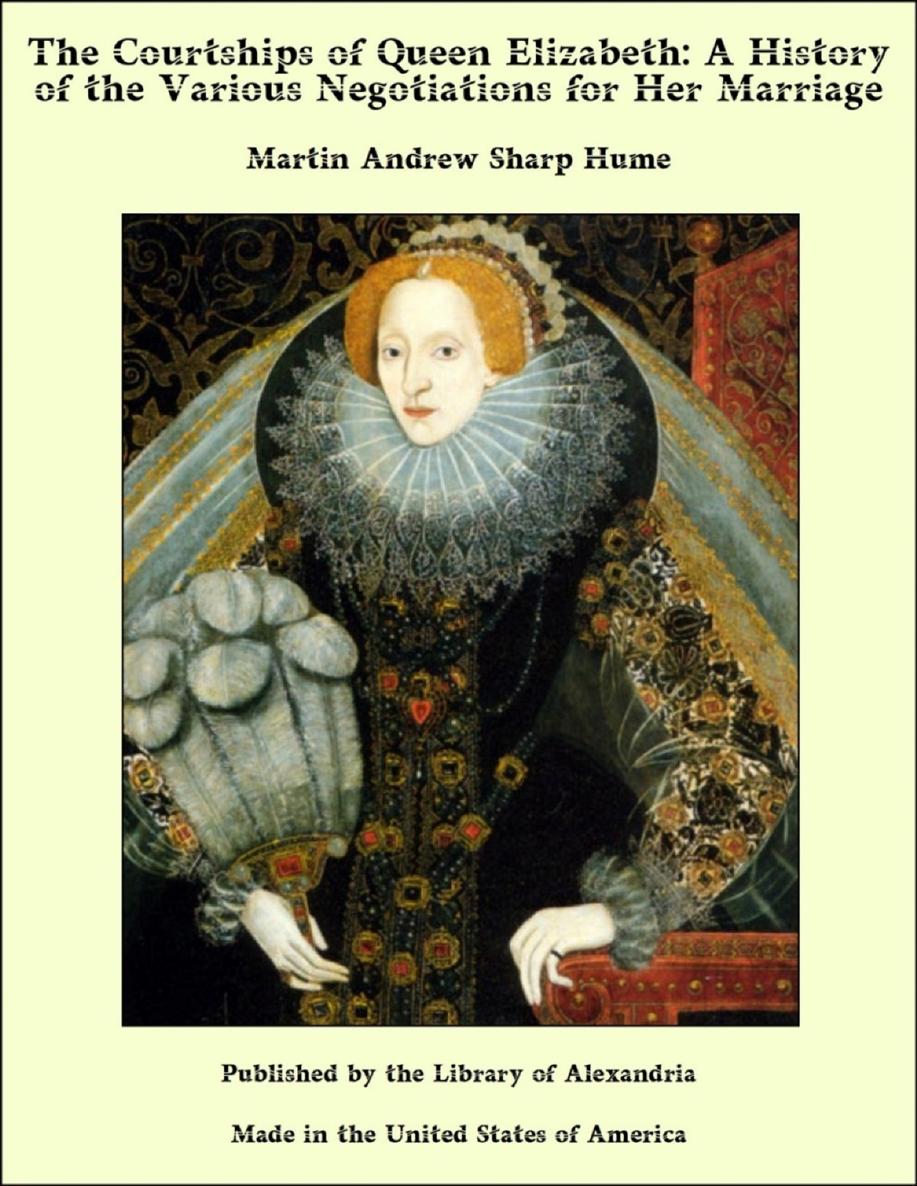

QUEEN ELIZABETH,

FROM THE ORIGINAL PORTRAIT BY ZUCCHERO,

IN HAMPTON COURT PALACE.

THE COURTSHIPS OF

QUEEN ELIZABETH

A HISTORY OF THE VARIOUS

NEGOTIATIONS FOR HER MARRIAGE

BY MARTIN A. S. HUME, F. R. HIST. S.

EDITOR OF THE CALENDAR OF SPANISH STATE

PAPERS OF ELIZABETH (PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE)

Coat of Arms

AND THE IMPERIAL VOTARESS PASSED ON

IN MAIDEN MEDITATION FANCY FREE

Midsummer Nights Dream

NEW YORK: MACMILLAN & Co.

LONDON: T. FISHER UNWIN

MDCCCXCVI

PREFACE.

It has been my pleasant duty to consider carefully in chronological order a great mass of diplomatic documents of the time of Elizabeth, in which are reflected, almost from day to day, the continually shifting aspects of political affairs, and the varying attitudes of the Queen and her ministers in dealing therewith. I have been struck with the failure of most historians of the time, who have painted their pictures with a large brush, to explain or adequately account for what is so often looked upon as the perverse fickleness of perhaps the greatest sovereign that ever occupied the English throne; and I have come to the conclusion that the best way in which a just appreciation can be formed of the fixity of purpose and consummate statecraft which underlay her apparent levity, is to follow in close detail the varying circumstances and combinations which prompted the bewildering mutability of her policy.

To do this through the whole of the events of a long and important reign would be beyond the powers of an ordinary student, and the attempt would probably end in confusion. I have therefore considered it best to limit myself in this book to one set of negotiations, those which relate to the Queens proposed marriage, running through many years of her reign: and I trust that, however imperfectly my task may have been effected, the facts set forth may enable the reader to perceive more clearly than hitherto, that capricious, even frivolous, as the Queens methods appear to be, her main object was rarely neglected or lost sight of during the long continuance of these negotiations.

That a strong modern England was rendered possible mainly by the boldness, astuteness, and activity of Elizabeth at the critical turning-point of European history is generally admitted; but how masterly her policy was, and how entirely personal to herself, is even yet perhaps not fully understood. I have therefore endeavoured in this book to follow closely from end to end one strand only of the complicated texture, in the hope that I may succeed by this means in exhibiting the general process by which England, under the guidance of the great Tudor Queen, was able to emerge regenerated and triumphant from the struggle which was to settle the fate of the world for centuries to come.

MARTIN A. S. HUME.

London , February, 1896.

CHAPTER I.

Character of Elizabeth and her contemporariesMain object of her policyYouth of ElizabethThe Duke of AngoulmePhilip of SpainSeymour and Catharine ParrMrs. Ashleys and Parrys confessionsExecution of SeymourProposed marriage of Elizabeth with a son of the Duke of FerraraWith a son of Hans Frederick of SaxonyCourtneyEmmanuel Philibert, Duke of SavoyPrince Eric of SwedenDeath of Queen MaryThe Earl of Arundel.

The greatest diplomatic game ever played on the worlds chessboard was that consummate succession of intrigues which for nearly half a century was carried on by Queen Elizabeth and her ministers with the object of playing off one great Continental power against another for the benefit of England and Protestantism, with which the interests of the Queen herself were indissolubly bound up. Those who were in the midst of the strife were for the most part working for immediate aims, and probably understood or cared but little about the ultimate result of their efforts; but we, looking back as over a plain that has been traversed, can see that, from the tangle of duplicity which obscured the issue to the actors, there emerged a new era of civilisation and a host of young, new, vigorous thoughts of which we still feel the impetus. We perceive now that modern ideas of liberty and enlightenment are the natural outcome of the victory of England in that devious and tortuous struggle, which engaged for so long some of the keenest intellects, masculine and feminine, which have ever existed in Europe. It seems impossible that the result could have been attained excepting under the very peculiar combination of circumstances and persons then existing in England. Elizabeth triumphed as much by her weakness as by her strength; her bad qualities were as valuable to her as her good ones. Strong and steadfast Cecil would never have held the helm so long if he had not constantly been contrasted with the shifty, greedy, treacherous crew of councillors who were for ever ravening after foreign bribes as payment for their honour and their loyalty. Without Leicester as a permanent matrimonial possibility to fall back upon, the endless negotiations for marriage with foreign princes would soon have become pointless and ineffectual, and the balance would have been lost. But for the follies of Mary Stuart, which led to her downfall and lifelong imprisonment, the Catholic party in England could never have been subjected so easily as it was. Elizabeth, with little fixed religious conviction, would, with her characteristic instability, almost certainly at one difficult juncture or another have been drawn into a recognition of the papal power, and so would have destroyed the nice counterpoise, but for the unexampled fact that such recognition would have upset her own legitimacy and right to reign. The combination of circumstances on the Continent also seems to have been exactly that necessary to aid the result most favourable to English interests; and the special personal qualities both of Philip II. and Catharine de Medici were as if expressly moulded to contribute to the same end. But propitious, almost providential, as the circumstances were, the making of England and the establishment of Protestantism as a permanent power in Europe could never have been effected without the supreme and sustained statecraft of the Queen and her great minister. The nimble shifting from side to side, the encouragement or discouragement of the French and Flemish Protestants as the policy of the moment dictated, the alternate flouting and flattering of the rival powers, and the agile utilisation of the Queens sex and feminine love of admiration to provoke competing offers for her hand, all exhibit statesmanship as keen as it was unscrupulous. The political methods adopted were perhaps those which met with general acceptance at the time, but the dexterous juggling through a long course of years with regard to Elizabeths marriage is unexampled in the history of government. Not a point was missed. Full advantage was taken of the Queens maiden state, of her feminine fickleness, of her solitary sovereignty, of her assumed religious uncertainty, of her accepted beauty, and of the keen competition for her hand. In very many cases neither the wooer nor the wooed was in earnest, and the courtship was merely a polite fiction to cover other objects; but at least on two occasions, if not three, the Queen was very nearly forced by circumstances or her own feelings into a position which would have made her marriage inevitable. Her caution, however, on each occasion caused her to withdraw in time without mortal offence to the family of her suitor; and to the end of her days she was able, painted old harridan though she was, to act coquettishly the part of the peerless beauty whose fair hand might possibly reward the devoted admiration paid to her, with their tongues in their cheeks, by the bright young gallants who sought her smiles. The story of the various negotiations for the Queens marriage has been told in more or less detail in the histories of the times, but no comprehensive view has yet been given of the marriage negotiations alone: nor has their successive relation to other events been set forth as a connected narrative. Within the last few years much new material for such a narrative has become available both in England and on the Continent, and it is now possible to see with a certain amount of clearness the hands of the other players besides that of the English Queen. The approaches made to Elizabeth by the brothers de Valois, or rather by their intriguing mother, Catharine de Medici, have been related somewhat fully, mainly from the documents in the National Library in Paris, by the Count de la Ferrire, puts us into possession of a vast quantity of hitherto unused material of the highest interest, especially with regard to the matrimonial overtures made by Philip II. and the princes of the house of Austria; whilst the full text of the extraordinary private letters to and from the Queen in relation to the Alenon match, 157982, printed by the Historical MSS. Commission from the Hatfield Papers, affords an opportunity of the greatest value for criticising the by-play in this curious comedy. From these sources, from the Walsingham Papers from the French diplomatic correspondence, from the Foreign, Domestic, and Venetian Calendars of State Papers, and from the various contemporary and later chroniclers of the times, it is proposed to construct a consecutive narrative of most of the important attempts made to persuade the Virgin Queen to abandon her much-boasted celibacy.