BLUE LINES

Praise for the series:

It was only a matter of time before a clever publisher realized that there is an audience for whom Exile on Main Street or Electric Ladyland are as significant and worthy of study as The Catcher in the Rye or Middlemarch The series is freewheeling and eclectic, ranging from minute rock-geek analysis to idiosyncratic personal celebration The New York Times Book Review

Ideal for the rock geek who thinks liner notes just arent enough Rolling Stone

One of the coolest publishing imprints on the planet Bookslut

These are for the insane collectors out there who appreciate fantastic design, well-executed thinking, and things that make your house look cool. Each volume in this series takes a seminal album and breaks it down in startling minutiae. We love these. We are huge nerds Vice

A brilliant series each one a work of real love NME (UK)

Passionate, obsessive, and smart Nylon

Religious tracts for the rock n roll faithful Boldtype

[A] consistently excellent series Uncut (UK)

We arent naive enough to think that were your only source for reading about music (but if we had our way watch out). For those of you who really like to know everything there is to know about an album, youd do well to check out Bloomsburys 3313 series of books Pitchfork

For reviews of individual titles in the series, please visit our blog at 333sound.com

and our website at http://www.bloomsbury.com/musicandsoundstudies

Follow us on Twitter: @333books

Like us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/33.3books

For a complete list of books in this series, see the back of this book.

Forthcoming in the series:

Diamond Dogs by Glenn Hendler

The Wild Tchoupitoulas by Bryan Wagner

Timeless by Martin Deykers

Tin Drum by Agata Pyzik

Voodoo by Faith A. Pennick

xx by Jane Morgan

Band of Gypsys by Michael E. Veal

Judy at Carnegie Hall by Manuel Betancourt

From Elvis in Memphis by Eric Wolfson

Ghetto: Misfortunes Wealth by Zach Schonfeld

Im Your Fan: The Songs of Leonard Cohen by Ray Padgett

Suicide by Andi Coulter

The Velvet Rope by Ayanna Dozier

Blue Moves by Matthew Restall

Live at the Harlem Square Club, 1963 by Colin Fleming

Murder Ballads by Santi Elijah Holley

Once Upon a Time by Alex Jeffery

Tapestry by Loren Glass

The Archandroid by Alyssa Favreau

Avalon by Simon Morrison

Rio by Annie Zaleski

Vs. by Clint Brownlee

and many more

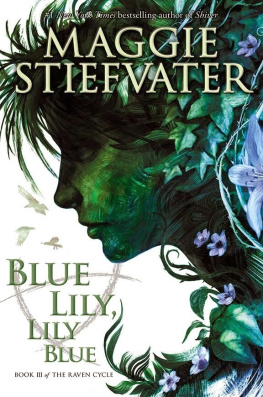

Blue Lines

Ian Bourland

Contents

1.Safe from Harm (5:18)

2.One Love (4:48)

3.Blue Lines (4:21)

4.Be Thankful for What Youve Got (4:09)

5.Five Man Army (6:04)

6.Unfinished Sympathy (5:08)

7.Daydreaming (4:14)

8.Lately (4:26)

9.Hymn of the Big Wheel (6:36)

Massive Attacks first full-length record Blue Lines was a warning shot in the new British Invasion of the 1990s, and a harbinger of what it might have been. If you remember the era as a time of Mancunian sneers, tabloid fisticuffs, and epic guitar rock, Massive was a marked counterpoint. They replaced nostalgia with futurity, a whitey rock n roll format with a notably afro-diasporic one. They showed that England was more than lads and pints, as a cosmopolitan hub that would define European lifeand dance musicfor most of the 1990s and beyond. A knowing alchemy of soul hooks, hip-hop production, dub instrumentation, and urbane lyrical stanzas, Blue Lines was an opening salvo of an age to come, one that was more world-weary, more optimistic, and more interconnected all at once. The year was 1991, the long 1980s of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan was over, and the people marginalized by conservativism and its visions of cultural purity had reason for optimism. An era of musical sophistication, sensual contemplation, and new freedoms seemed to beckon, the yobs and Little Englanders be damned.

Some may say theyve never heard of Massive Attack, but the sonic palette they ushered in provided the mise-en-scne for a great deal of popular culture. This was especially true in an increasingly integrated Europe, but also in global cities where new forms of electronic music cross-pollinated through raves and megaclubs, downtown bars and after-hours cafsfrom Washington, DC, to Mexico, DF, from Tel Aviv to Tokyo. There was a new, borderless map of pop music just starting to unfold, and records like Blue Lines , with all of its stylistic catholicism, were its lingua franca.

Blue Lines conjures a specific time and place, but also envisions a dreamy placelessness, which is why it has often been called introspective or minimal. Theres an intimacy and interiority to it that plays well basically anywhere with buildings and nighttime. If you missed that, you probably saw the movie Hackers in 1995, heard the song Protection, with its spare wah-wah guitar and subtle breakbeat drifting under Tracey Thorns heartswelling lyrics. Its the soundscape for the arch gen-X romance between Angelina Jolie and Jonny Lee Millerunsentimental, but somehow sincere. Protection remains insistently familiar and, although it appeared on the 1994 follow-up to Blue Lines , its production and its sonic textures are emblematic of a style and ethos that the record conceived. The song defines a cinematic and urban sensibility that was very much of its time and, indeed, many peoples deep memory pathways. With the exception of Motown Philly or Smells Like Teen Spirit, it is the defining song of the early 1990s. Or, at least, the aural embodiment of a world coming into focus that was often defiantly and self-consciously global.

Of course, much of the optimism of the 1990s and its so-called New World Order feel misplaced in hindsight. Back then, the Cold War was over, prosperity and multiculturalism seemed to be on the march. But with Brexit and the Grenfell Tower inferno and the ascent of the far-right, it feels like the bad-old-days of the 1980s againor worse. Its bittersweet to look back on the comparative exuberance and innocence of that time. And Massives own material grew darker, more serious as the years wore on.

Im not arguing here that Blue Lines was the groups best recordthat would be 1998s Mezzanine , a definitive masterpiece with a coherent sound (all minor keys and subtle instrumentation). But Mezzanine is heavy listening. Its suffused by a shadowy monochrome that looks ahead into the next decade, one defined by a global war on terror, surveillance, and all the rest. Its opener, Angel, was used to great effect in The West Wing , the unnerving crescendo as the Presidents daughter is abducted by foreign agents. It also frames an inferno at a trailer park as Brad Pitt looks on, enraged, in Snatch (2000). And, of course, Tear Drop featured as the intro to dark medical drama House , which closed out the aughts on an acidic note.

Which is to say that Mezzanine revealed Massive as artists: people who make elegant, difficult work; people who name records after obscure islands in the North Sea; people who seem to disappear for years on end, sometimes resurfacing to tour with avant-garde filmmaker Adam Curtis, or speak out against a venue in Bristol named in honor of a prominent slave trader. Mezzanine is the kind of record that serious people take seriously, but its no ones favorite record. It doesnt conjure warm memories or happy firsts.