Into the Blue

A sea of blue thoughts pours forth over my heart.

Heinrich Heine

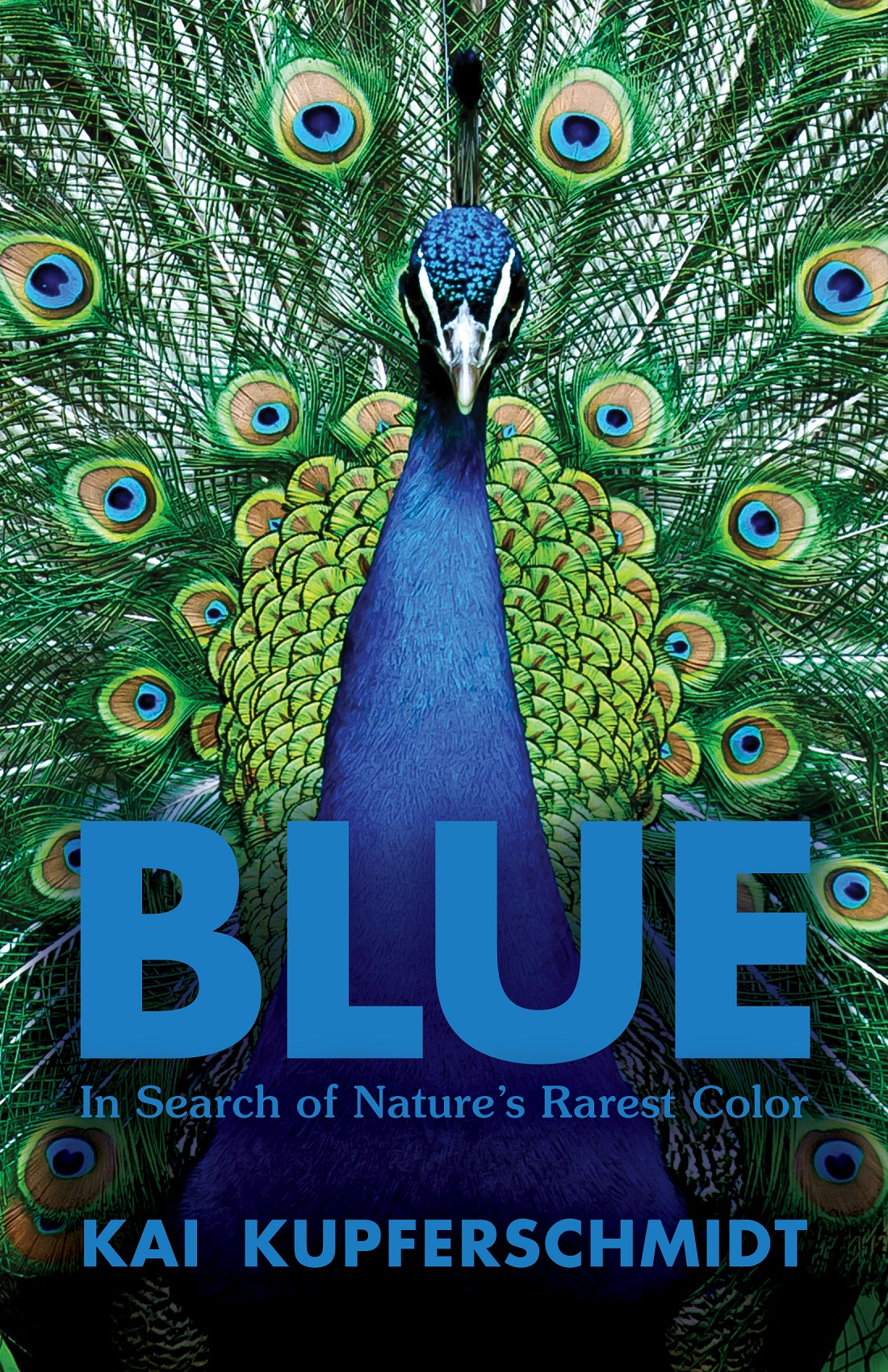

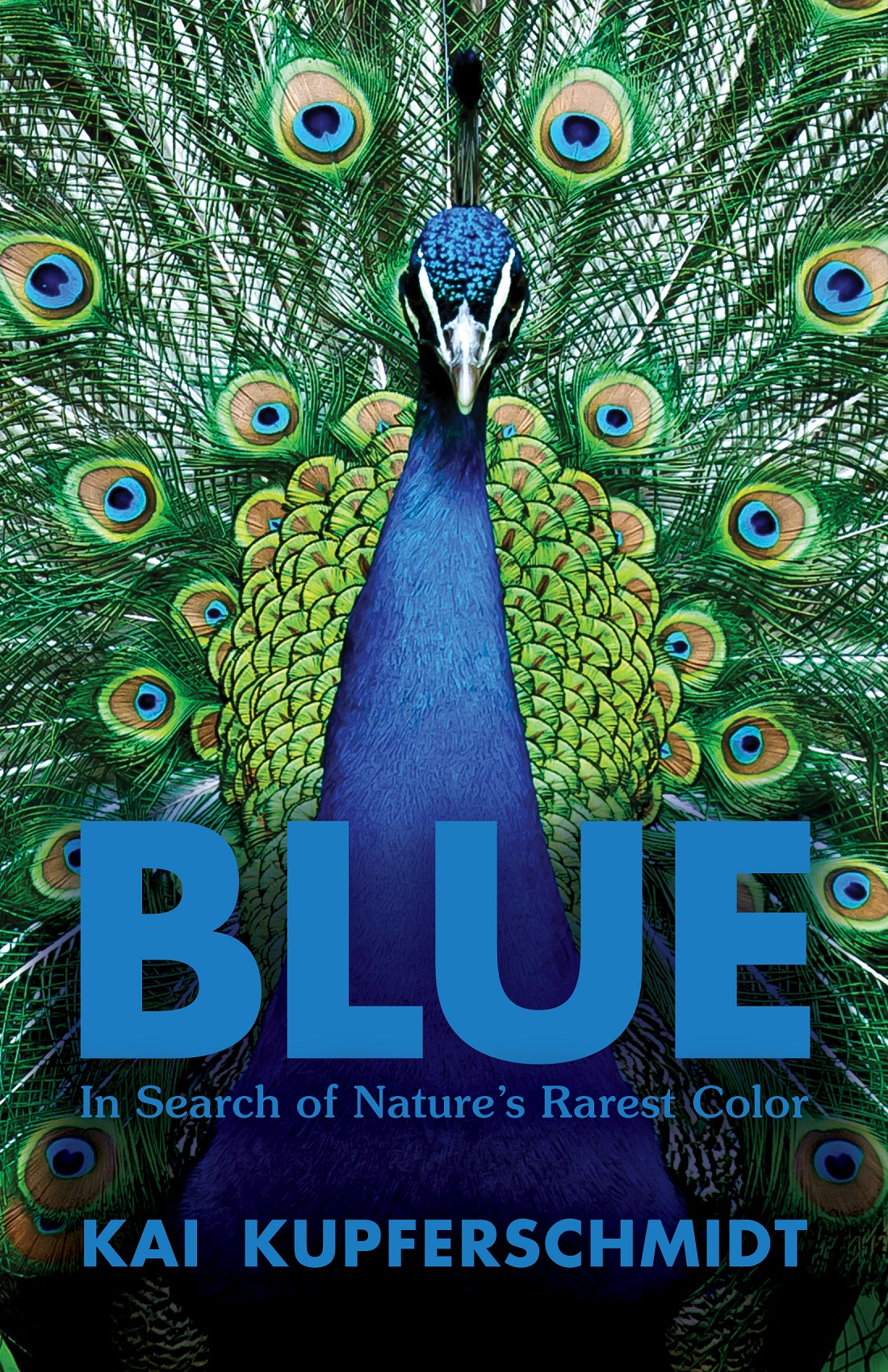

Blue: In Search of Natures Rarest Color

Copyright 2019 by Hoffmann und Campe Verlag, Hamburg

Translation copyright 2021 by The Experiment, LLC

The is a continuation of this copyright page.

Originally published in Germany as Blau by Hoffmann und Campe Verlag, Hamburg, in 2019. First published in English in North America in revised form by The Experiment, LLC, in 2021.

All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in newspaper, magazine, radio, television, or online reviews, no portion of this book may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

The Experiment, LLC

220 East 23rd Street, Suite 600

New York, NY 10010-4658

theexperimentpublishing.com

THE EXPERIMENT and its colophon are registered trademarks of The Experiment, LLC. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book and The Experiment was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been capitalized.

The Experiments books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk for premiums and sales promotions as well as for fund-raising or educational use. For details, contact us at .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kupferschmidt, Kai, author.

Title: Blue : in search of natures rarest color / Kai Kupferschmidt.

Other titles: Blau. English

Description: New York : The Experiment, 2021. | Originally published in

Germany as Blau by Hoffmann und Campe Verlag, Hamburg, in 2019. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021001385 (print) | LCCN 2021001386 (ebook) | ISBN

9781615197521 | ISBN 9781615197538 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Blue. | Colors. | Colors in nature.

Classification: LCC QC495.8 .K8713 2021 (print) | LCC QC495.8 (ebook) |

DDC 535.6--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021001385

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021001386

ISBN 978-1-61519-752-1

Ebook ISBN 978-1-61519-753-8

Inquisitive, Inc., edition ISBN 978-1-61519-846-7

Jacket and text design by Beth Bugler

Cover photograph by iStock.com/Hans Harms

Author photograph by IMAGO/Sven Simon

Translation by Mike Mitchell

Manufactured in China

First printing May 2021

First printing Inquisitive, Inc., edition March 2021

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

O ne of the most famous photos of all time was not taken on Earth. It shows Earth. On December 7, 1972, the astronauts of Apollo 17, the last manned Moon mission, aimed a camera at theirourhome planet.

On the globe, Africa and the Arabian Peninsula can be seen in shades of green and brown. From the ice cap around the South Pole white clouds seem to be swirling away, as if in a Van Gogh. The rest is blue: the Indian and Atlantic Oceans, the Red Sea and the Mediterranean. The Blue Marblethats how the photo has come to be known.

A few years ago, I was traveling on one of those patches of blue. It was summer, and I was standing on the deck of a ferry taking me from Athens to one of the numerous Greek islands. Suddenly a question flashed through my mind: How would I explain the color blue to a blind person?

Curving above me was the shining blue of heaven and, stretching out all around me, the deep sea blue of the Aegean. I felt I was hovering between those two spheres of infinite blue. It was a sublime moment. But how could I explain that feeling to someone who didnt know what blue is?

And what is blue, anyway?

Is the color cool? Calm? Wet? Is blue the taste of blueberries? The smell of the sea? The feeling you have when your teeth are chattering with cold?

It is no accident that this question occurred to me about blue of all colors. Throughout the world, blue is the most popular color for both men and women. Goethe felt that the color had a peculiar and almost indescribable effect on the eye. In the Middle Ages, the pigment ultramarine was worth its weight in gold. Pablo Picasso had his Blue Period, and the painter Henri Matisse was fascinated by a blue butterfly. The French artist Yves Klein saw the transition from the material to the immaterial in the color. The deeper the blue the more it beckons man into the infinite, arousing a longing for purity and the supersensuous, wrote Wassily Kandinsky, one of the founding members of the group of artists known as the Blue Rider.

Colour is first and foremost a social phenomenon, the cultural historian Michel Pastoureau wrote in his book about the history of blue.

It is that, too. But above all? Is the sky a social phenomenon? The sea? A rainbow? Is the sense of vastness that blue creates?

Blue is physics. Back then, aboard the ferry, I couldnt have explained it precisely, but I knew that the sky and the sea are blue because light of a certain wavelength interacts in a particular way with the molecules in the air and the water.

Blue is chemistry. Lapis lazuli develops under certain conditions in Earths crust when limestone comes into contact with hot magma. Dyeing with indigo demands some clever chemistry in order to transfer the blue pigment to cloth; it is the behavior of these pigment molecules that we have to thank for our much-loved denim. And one of the shades of blue used by Picasso was developed by alchemists in Berlin, who were actually looking for a wonder drug to cure all disease.

Blue is biology. Long before painters were bringing beauty to a canvas with their brushes, there were shimmering blue butterflies and flowers blooming in blue. Evolution produced them, as it did our ability to appreciate the colorful spectacle of life.

Blue is special. It occurs less frequently in nature than other colors do, as Goethe himself noted in his Theory of Colours. Why? What does science know about the color blue? What is the connection between all these things we admire: the butterflies and the berries, the sea and the stones and our senses? How much more beauty is there for us to discover if we know what it is that connects them? In short: How would I explain blue to a person who can see?

Blue stones such as lapis lazuli or sapphire derive their color from grids of crystals in which elements such as sulfur, iron, copper, or cobalt arrange themselves in a particular way. Humans have learned from some of these stones how to create inorganic pigments in order to use them in our art. In plants, it is organic pigments, large molecules based on carbon, that make them appear blue. These inorganic and organic pigments form the basis of most of the shades of blue around us.

In the animal world, blue comes about in a different way. Most animals manage without any blue pigments. Instead, tiny patterns on their bodies surfaces manipulate rays of light directly so that blue light is intensified. In birds feathers and butterflies scales, nature has mastered a technology that humans are only just beginning to understand at the dawn of the twenty-first century.

Yet the beauty of all these stones, plants, and animals also lies in the eye (and brain) of the beholder. Our eyes transform the rays of light they reflect into electrical signals, our brain interprets these signals, and our language arranges these impressions into colors. Blue is not out there, and it is not inside us, either. The radiant blue of a cornflower is a kind of collaboration between us and the plant.

Next page