CASS SERIES: STUDIES IN INTELLIGENCE

(Series Editors: Christopher Andrew and Michael I. Handel)

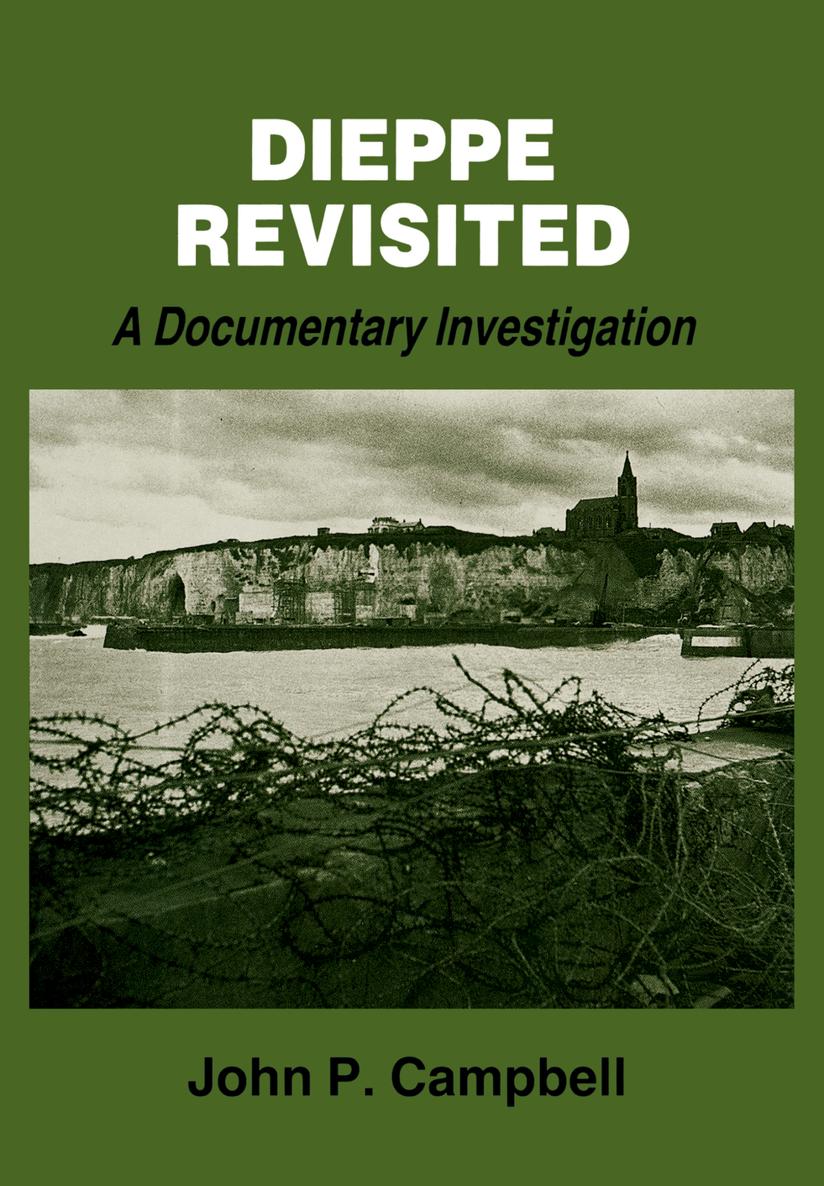

DIEPPE REVISITED

A Documentary Investigation

Also in this series

Codebreaker in the Far East

by Alan Stripp

War, Strategy and Intelligence

by Michael I. Handel

A Don At War (revised edition)

by Sir David Hunt

Controlling Intelligence.

edited by Glenn P. Hastedt

Security and Intelligence in a Changing World: New Perspectives for the 1990s

edited by A. Stuart Farson, David Stafford and Wesley K. Wark

Spy Fiction, Spy Films and Real Intelligence

edited by Wesley K. Wark

From Information to Intrigue: Studies in Secret Service

Based on the Swedish Experience 1939-45

by C.G. McKay

The Australian Security Intelligence Organization;

An Unofficial History

by Frank Cain

Intelligence and Strategy in the Second World War

Edited by Michael I. Handel

Policing Politics: Security Intelligence

and the Liberal Democratic State

by Peter Gill

Dieppe Revisited

A Documentary Investigation

John P. Campbell

First published 1993 in Great Britain and in the United States of America by

FRANK CASS & CO. LTD.

Published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1993 John P. Campbell

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Campbell, John P.

Dieppe Revisited: Documentary Investigation. (Studies in Intelligence Series)

I. Title II. Series

940.54

ISBN 978-0-7146-3496-8

ISBN 978-1-3150-3591-8 (eISBN)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Campbell, John P.

Dieppe revisited: a documentary investigation / John P. Campbell.

p. cm. -- (Cass series--studies in intelligence)

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-7146-3496-8

ISBN 978-1-3150-33591-8 (eISBN)

1. Dieppe Raid, 1942. 2. Dieppe Raid, 1942--Sources. 3. Deception (Military science) 4. Military intelligence--Great Britain. I. Title. II. Series.

D756.5.D5C36 1993

940.54'21425--dc20

9219265

CIP

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Contents

I should like to thank the Trustees of the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives for permission to quote from the Liddell Hart Papers; the Trustees of the Broadlands Archives Trust and Lord Tweedsmuir for permission to include quotations from the Mountbatten Papers; and the Trustees of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, for permission to publish material from the Papers of Admiral T. Baillie-Grohman. I am also grateful to the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office for permission to reproduce three of the 'Plans' contained in the Naval Staff History (Battle Summary No 33) of the raid on Dieppe.

My main debt of gratitude in a work of this description is bound to be to the professional staffs of the four main repositories where I did my research: the Public Record Office in London, the National Archives in Washington, the National Archives of Canada in Ottawa, and the Bundesarchiv-Militrarchiv in Freiburg-im-Breisgau. Time and again I was reminded that the archivist is the historian's best friend. Harry Rilley in Washington was particularly helpful in tackling the German naval documents on microfilm. Although my emphasis was on official records, there was always the temptation to appeal for elucidation of some particularly thorny point to a knowledgeable authority, a temptation to which I yielded on a number of occasions. Patrick Beesly, Sir Harry Hinsley, Sir Michael Howard, Ewen Montagu, Captain S. Roskill and Willi Weber were all generous with their replies to my queries, some of which probably struck them as rather far-fetched. I had the honour not only of corresponding with but actually meeting Professor R.V. Jones and David Mure. The only veteran of the Dieppe raid I interviewed was Jack Nissen, who patiently explained some of the basic facts of electronics to this scientific ignoramus; it is accordingly with genuine regret that I find my reading of the documents at odds with Jack's recent claims based on his exploits on 19 August 1942. Another expert who dazzled me with science was J.R. Robinson, who was good enough to read my chapter on radar.

Finally, three fellow historians made a contribution to the writing of this book: Brian Villa kept to the informal agreement we made in Vancouver in 1983 to 'divide' the topic and unintentionally acted as a goad by publishing his own book to great acclaim in 1989; and Bob Johnston and Dick Rempel, the best of friends and colleagues, read the text and offered invaluable advice on everything from umlauts to organization. My deepest debt of all is to my wife, Jennie, who shared the joys and rigours of many a research trip, and who never once complained that it was taking so long to finish this project.

John P. Campbell,

Ancaster, Ontario

Much confusion can be averted by bearing in mind that German T(orpedo)-boats were really small destroyers: in fact the earliest Type (1923), to which Seeadler belonged, was initially classified as such. T-boats were slightly smaller in displacement than the Hunt Class of escort destroyers which began to appear in the Channel in 1940/41. Calpe , for instance, was a Type II Hunt displacing 1050 t standard, with a complement of 168; Iitis, 924 t standard, with a ship's company of 127. The T-boats were capable of speeds in excess of 30 knots, compared with 27 knots for Calpe and her Class, which had no torpedo armament. The true German equivalent of the British Motor Torpedo Boat was the formidable E-boat, or S(chnell)-Boot, with two fixed torpedo tubes forward, a speed in excess of 35 knots, and a crew of about 20, depending on Type. Altogether the Kriegsmarine commissioned 249 E-boats. With a length of 114 ft, they were easily confused in PRU photographs of dockyards with the much slower R(um)-Boote of 116 ft. R-boats were small motor minesweepers with a complement of 34/38, no torpedo armament but a heavier gun armament than the E-boats. Like the even slower V(orposten)-Boote, which were mostly armed trawlers, they were often pressed into service as convoy escorts. M-Class minesweepers were excellent, versatile ships of 680 t standard and a complement of 95/113, capable of being used as escorts, submarine chasers, or minelayers. U-Jager did not denote a standard A/S type of vessel but covered all that were equipped for A/S duties, such as UJ 1404, a converted deep-sea trawler equipped with 60 depth charges, detection gear and an 88 mm gun as main armament. Sperrbrecher were usually converted tramp steamers whose crews had the unenviable task of detonating mines by contact, British MTBs and MGBs were powered by noisy petrol engines. It was in an attempt to overcome this disadvantage that the Steam Gunboat was designed (34 knots, 175 t standard, crew of 27), but the SGB proved to be rather too vulnerable to be called a complete success.