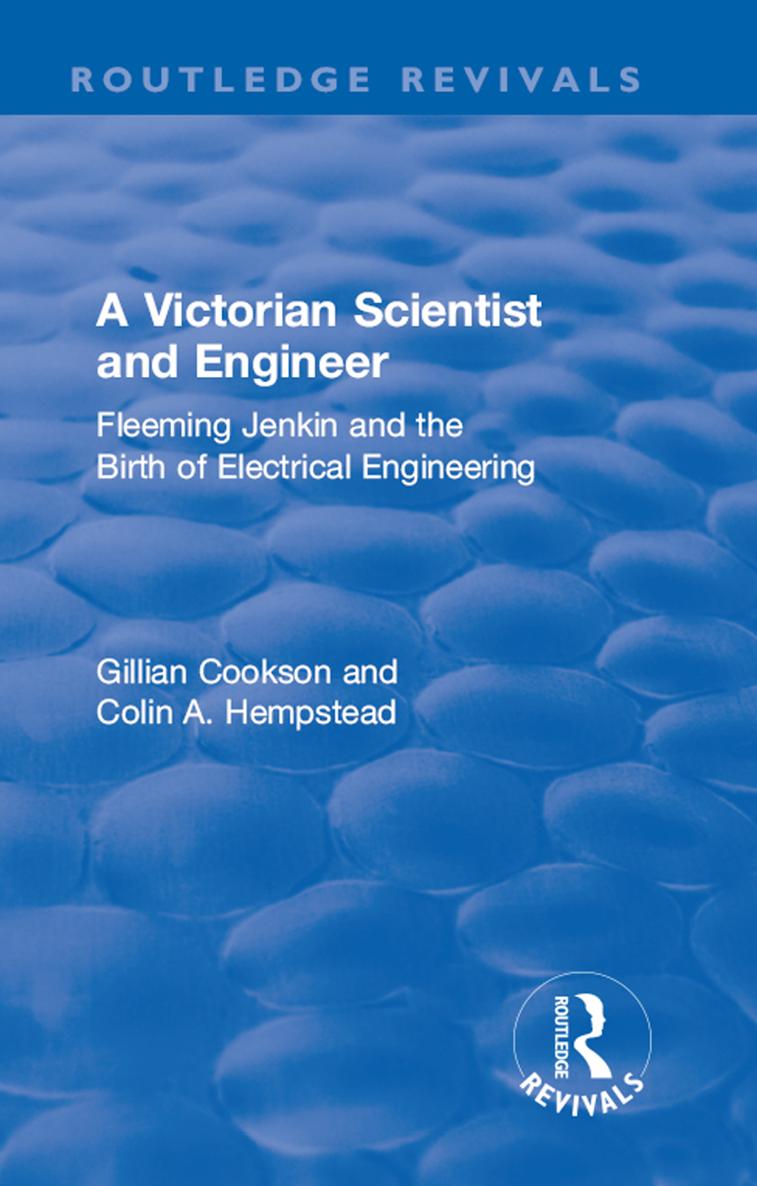

First published 2000 by Ashgate Publishing

Reissued 2018 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2000 Gillian Cookson and Colin A. Hempstead.

The authors have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the authors of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

A Library of Congress record exists under LC control number: 99041823

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-70266-0 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-315-20355-3 (ebk)

The Right Honourable the Lord Jenkin of Roding

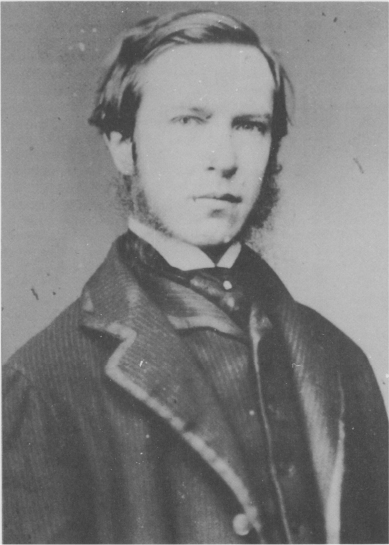

On a recent visit to the Institution of Civil Engineers I found myself gazing up at the portrait there of William Thomson, Lord Kelvin. It is typical of its genre dark, formal, dignified, imposing; the tall, gaunt, bearded figure gazes down on the lesser mortals around him. The painter has caught not only the distinction of one of the greatest of the Victorian engineers but also the formidable authority of the man.

Yet having read and reread this biography of Thomsons collaborator and business partner, my great-grandfather, Professor Fleeming Jenkin, I could not avoid seeing also something of the self-regarding pride which seems to have made it difficult for him to give the younger man full credit for the latters undoubted achievements. Indeed, as Dr Cookson and Dr Hempstead recount, Thomsons obituary of his recently deceased partner, written for the Royal Society, reflected his view that any importance which attached to Jenkin flowed only from his relationship with Thomson, a relationship in which Jenkin was very much subordinate. Compared with the tributes to be found in other appreciations of Jenkins life of achievement (not least the Institution of Civil Engineers own eloquent obituary) this unwillingness to recognise what other contemporary engineers gladly acknowledged may partly account for Jenkin being regarded for many years as a somewhat obscure, minor figure.

There is another, quite different, reason why it is not until recently that Jenkins contributions to the science of electromagnetism have not been more widely recognised. The only previous record of his life before this new biography was the Memoir written soon after his death in 1885 by his friend, Robert Louis Stevenson. As Cookson and Hempstead make clear, Stevenson had no love for and little interest in electrical engineering. Indeed, some of the major discoveries of the era receive no mention whatever in the Memoir, let alone Jenkins seminal contributions to those discoveries. Yet the Memoir is a lovely book, full of all sorts of reminiscences and events, capturing much of the extraordinary personality of his dear friend. My copy has been well thumbed by successive generations of the Jenkin family.

It was not until I was invited to contribute to a symposium on Clerk Maxwell and his Circle in 1995, that I began to find out just why Fleeming Jenkin should be seen as one of the leading engineers of his age. As I delved for the first time into the biographies of such eminent men as Sir William Thomson, later Lord Kelvin, P.G. Tait, Sir Alfred Ewing and, of course, James Clerk Maxwell himself, I found myself agreeing with Sir Alfred Ewing, who was perhaps Fleeming Jenkins most distinguished pupil, that Fleeming Jenkin was not well served by his biographer. This new biography by Cookson and Hempstead more than makes up for the shortcomings of the earlier work, and does so comprehensively and with considerable authority. The reader needs only to glance through the copious footnotes and references to appreciate that a deal of painstaking research lies behind this new work. Yet, dare I suggest, the reader who wishes to understand just why Fleeming Jenkin attracted such wide affection and admiration from his circle of friends and colleagues, and why his premature death from septicaemia caused such deep sadness, needs to read both books. This is not meant as any criticism of the authors work; it is simply that a modem history, however carefully researched, cannot capture the emotions of those who knew the man intimately and admired the complex personality that lay behind his eventful career.

It is not the purpose of this brief Foreword to attempt a critique of the book. I am content to let readers make their own judgements. What I seek to do is to draw out a few threads from my great-grandfathers life that have a relevance to the modem world. Of course, technology has moved forward in ways which he and his contemporaries would find incredible: the transistor and silicon chip, wireless communications, opto-electronics, and advances into space and satellite communications all these have created a world of which nineteenth-century engineers could scarcely have dreamed. If one throws in nuclear fission, particle physics and radio astronomy, it would be easy to imagine that there could be little or nothing in common between those early telegraph pioneers and todays generation of scientists and engineers.

But that would be to assume that we have nothing learn from history. As I read this book, I was struck again and again by how much there is that is relevant to us today. For instance, the relationship between industry and academia, a very contemporary issue, was an important theme in Fleeming Jenkins life. Then, as now, in a fast moving technological environment commercial developments ran far ahead of the generality of university teaching. Industry was leading in the science as well as in its application, and the universities were hard pressed to keep up. A parallel today is the Internet and the World Wide Web, where most universities can do little more than try to keep abreast of what is happening in industry.

For many engineers who read this book, the section on the education and training of engineers will be of great interest. Fleeming Jenkin, coming from industry into academia, wanted his students both to have a firm grounding in the theoretical science of the subject, and to acquire the practical skills they would need in industry. Jenkins philosophy of engineering education lives on today in many universities. The terms of his employment allowed him to continue with his consultancies, and some of his most notable achievements were made after he took up his appointment in Edinburgh. In particular, what some regard as Jenkins chief claim to an honoured place in the history of science, his work for the British Associations Committee on Electrical Standards led to the adoption of standards of absolute electrical measurement the ohm, the ampere, and other standards which are in general use across the world.