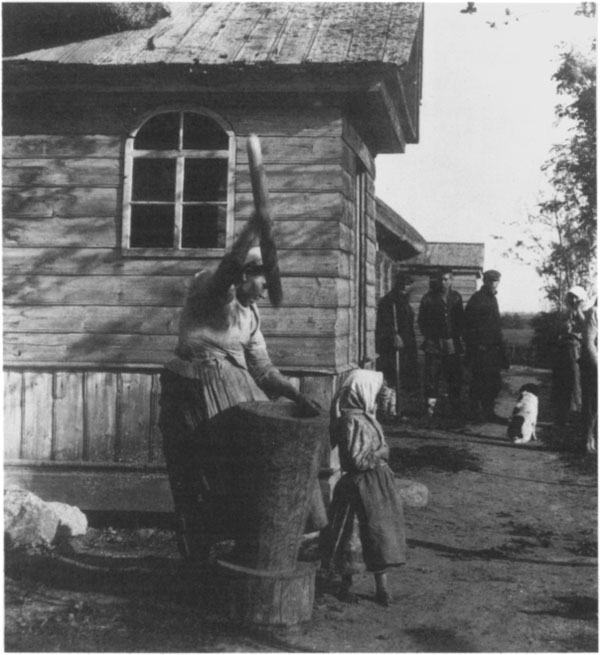

Village Life

in Late Tsarist RussiaIndiana-Michigan Series in Russian and

East European Studies

Alexander Rabinowitch and William G. Rosenberg,

general editors

Advisory Board

Deming Brown | Ben Eklof |

Jane Burbank | Zvi Gitelman |

Robert W. Campbell | Hiroaki Kuromiya |

Henry Cooper | David Ransel |

Herbert Eagle | Ronald Grigor Suny |

William Zimmerman

Village Life

in Late Tsarist Russia

by

OLGA SEMYONOVA TIAN-SHANSKAIA

EDITED BY DAVID L. RANSEL

Translated by David L. Ransel with Michael Levine

Indiana

University

Press

BLOOMINGTON AND INDIANAPOLIS

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

601 NORTH MORTON STREET

BLOOMINGTON, IN 47404-3797 USA

HTTP://IUPRESS.INDIANA.EDU

Telephone orders 800-842-6796

Fax orders 812-855-7931

Orders by e-mail

1993 by David L. Ransel

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Semyonova Tian-Shanskaia, Olga, 18631906.

Village life in late tsarist Russia : an ethnography by Olga

Semyonova Tian-Shanskaia / edited by David L. Ransel : translated by

David L. Ransel, with Michael Levine.

p. cm. (Indiana-Michigan series in Russian and East

European studies)

Translated from Russian.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-253-34797-8 (alk. paper). ISBN 978-0-253-20784-5 (pbk.)

1. RussiaRural conditions. 2. RussiaSocial conditions

18011917. 3. VillagesRussiaHistory19th century. 4. Sex

customsRussiaHistory19th century. I. Ransel, David L.

II. Title. III. Series.

HN523.S46 1993

307.720947dc20

92-28558

8 9 10 11 12 13 12 11 10 09 08

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project has been assisted by support from a number of foundations and individuals. A Mellon Grant through the Russian and East European Institute of Indiana University paid Michael Levine for his collaboration in the translation. During 1989-1990, when I received funding from the Guggenheim Foundation, the International Research and Exchanges Board (IREX), and a Fulbright-Hays fellowship, I was able to devote a portion of my time to this project, in particular the work in Russian archives. I am grateful to the donors and staffs of these funding agencies for their generous support.

Several individuals contributed important advice. Professors Nadya Peterson of the University of Pennsylvania, Nina Perlina of Indiana University, and Yelena Stepanova of Yekaterinburg Technical University helped me understand some difficult phrases in-Russian, especially in the expressions of the peasants. Professor Linda Ivanits of Pennsylvania State University advised on some of the folkloric terms; Olga Melnikova, a curator in the Kremlin museum, provided crucial information on the Semyonov Tian-Shanskii family from archives that I was unable to consult (I acknowledge her help again in the specific footnote references that she gave me). Materials from the Academy of Sciences Archive in St. Petersburg came to me through the mediation of Aleksandr Isupov, an advanced graduate student at St. Petersburg University. Professor Janet Kennedy and Mr. Eli Weinerman, both at Indiana University, helped with references and advice on pictures. Special appreciation goes to T. M. Pankova of the Riazan Historical-Architectural Museum in the city of Riazan for selecting from the museums photo archive many of the pictures used in this book, and to Ben Eklof and Molly Pyle for facilitating their delivery. Professor Ellen Dwyer of Indiana University took a sharp editorial pen to the introduction, and Professor Steven L. Hoch of the University of Iowa offered a number of valuable suggestions for improvement of both the introduction and the translation. To all these people, and to my wife Terry for her patience and understanding, I am most thankful.

Note on the Text

I have used the Library of Congress system of transliteration throughout; however, some minor modifications have been made in the text so that readers unfamiliar with Russian can approximate the correct pronunciation of names and terms. For example, the Russian letter has been rendered as yo; soft vowels are rendered as ya, yu, and ye at the beginning of a word, and as ia, iu, and e elsewhere. Soft signs have been omitted from transliterated Russian first names in the body of the book but retained in the notes for proper reference.

ABBREVIATIONS

AGO AN SSSR | Archive of the Russian Geographical Society, St. Petersburg |

Arkhiv AN SSSR | Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg branch |

LGALI | The Leningrad State Archive of Literature and Art |

INTRODUCTION

Russia in the late nineteenth century was a society in crisis. For some, the pace of development was too slow. Germany, France, England, and the United Statesthe countries to which most educated Russians instinctively compared their ownwere well ahead of Russia in industrialization and urbanization, and they had a far higher level of general education and culture. For others, change was too rapid. They blamed the governments drive to catch up with the West for the increasingly deep fissures in society, which seemed to threaten the country with revolution. Yet, however educated Russians may have viewed the sources of the crisis, most believed that its resolution depended ultimately on the attitudes and actions of the common people, the peasants, who constituted about 85 percent of the nations population. Peasants not only were rural dwellers, but they also, as migrant laborers in the cities and factory towns, made up the majority of the industrial working class. As peasants in uniform, they composed the bulk of the armed forces. Curiously enough, both radical critics of the established regime and its conservative defenders, despite their differences with one another and their shared ignorance of village life, were convinced that they knew what the common people wanted and needed and could speak in their name. As a consequence, discussion of peasants and of Russias future, an important part of public discourse in late tsarist Russia, was filled with a great many myths and misconceptions.