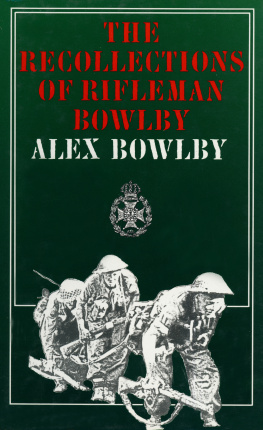

RECOLLECTIONS

OF

RIFLEMAN HARRIS,

( OLD 95th. )

WITH

title

EDITED BY

HENRY CURLING, Esq .,

HALF-PAY 52D FOOT,

AUTHOR OF "JOHN OF ENGLAND."

"This story

The world may read in me: my body's mark'd

With Roman swords;

And when a soldier was the theme, my name

Was not far off." Shakespeare.

LONDON:

H. HURST, 27, KING WILLIAM STREET,

CHARING CROSS.

1848.

CLAYTON AND CO, PRINTERS,

16, HART STREET, COVENT GARDEN.

NOTICE

Since the printing of this volume was commenced, "Rifleman Harris" has removed from Richmond Street, Soho, to 4, Upper James Street, Golden Square.

TO THE MOST NOBLE

THE MARQUESS OF LONDONDERRY,

G.C.B. and G.C.H. ,

COLONEL OF THE SECOND LIFE GUARDS, &c.&c.,

This Volume,

IN TOKEN OF HIGH ADMIRATION OF HIS LORDSHIP'S

CHIVALROUS BEARING

DURING THE BATTLES OF THE PENINSULA,

IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED,

BY HIS OBEDIENT SERVANT,

THE EDITOR.

London, March, 1848.

ADVERTISEMENT BY THE EDITOR.

The following pages, describing the chequered life of a private soldier, who served during the most glorious period of our military history, speak so plainly for themselves, as scarcely to need any introductory remarks from the editor, further than the assurance of his own sincere conviction of their truth. Such works as the narratives of Rifleman Harris, from the very nature of their details, afford occasionally more graphic sketches of the actual scenes of war, in its stern realities and concomitant circumstances, than the more stately and largely-grouped pictures of the Historian.

Nor are these humble records without their moral.

Many abuses and grievances are incidentally brought to light, that can be but rarely heeded in the excitement and bustle of active service, but which, nevertheless, for the good of the soldier, may be of sufficient importance to require correction.

The main source of our military superiority over foreign nations has been almost universally ascribed to the incomparable discipline of the British army. That the well-being and judicious treatment of the private soldier is the basis of this system can (we think) scarcely be doubted. To maintain this discipline it is surely incumbent on the officers to become acquainted with the nature and peculiar characteristics of the men they have to conduct and control, both in the elation of victory and the more difficult emergencies consequent upon retreat. How this is best effectedby what potent influence this mastery is exercisedand by what sort of standard the "rough and ready" private soldier estimates, and accordingly respects and obeys his officer, will be duly shewn in the autobiography of. Rifleman Harris.

Henry Curling.

March, 1848.

RECOLLECTIONS

OF

RIFLEMAN HARRIS ( Old 95th ).

CHAPTER I.

Recruiting for the Army of ReserveThe penalty for desertionGeneral Craufurd's cure for cowardice and treacheryTrial of General WhitelockIrish recruits and the shillelaghProtestant and CatholicDanish expeditionRiflemen at home.

My father was a shepherd, and I was a sheep-boy from my earliest youth. Indeed, as soon almost as I could run, I began helping my father to look after the sheep on the downs of Blandford, in Dorsetshire, where I was born. Whilst I continued to tend the flocks and herds under my charge, and occasionally (in the long winter nights) to learn the art of making shoes, I grew a hardy little chap, and was one fine day in the year 1802, drawn as a soldier for the Army of Reserve. Thus, without troubling myself much about the change which was to take place in the hitherto quiet routine of my days, I was drafted into the 66th Regiment of Foot, bid good-bye to my shepherd companions, and was obliged to leave my father without an assistant to collect his flocks, just as he was beginning more than ever to require one; nay, indeed, I may say to want tending and looking after himself, for old age and infirmity were coming on him; his hair was growing as white as the sleet of our downs, and his countenance becoming as furrowed as the ploughed fields around. However, as I had no choice in the matter, it was quite as well that I did not grieve over my fate.

My father tried hard to buy me off, and would have persuaded the Serjeant of the 66th that I was of no use as a soldier, from having maimed my right hand (by breaking the fore-finger when a child). The Serjeant, however, said I was just the sort of little chap he wanted, and off he went, carrying me (amongst a batch of recruits he had collected) away with him.

Almost the first soldiers I ever saw were those belonging to the corps in which I was now enrolled a member, and, on arriving at Winchester, we found the whole regiment there in quarters. Whilst lying at Winchester (where we remained three months), young as I was in the profession, I was picked out, amongst others, to perform a piece of duty that, for many years afterwards, remained deeply impressed upon my mind, and gave me the first impression of the stern duties of a soldier's life. A private of the 70th Regiment had deserted from that corps, and afterwards enlisted into several other regiments; indeed, I was told at the time (though I cannot answer for so great a number) that sixteen different times he had received the bounty and then stolen off. Being, however, caught at last, he was brought to trial at Portsmouth, and sentenced by general court-martial to be shot.

The 66th received a route to Portsmouth, to be present on the occasion, and, as the execution would be a good hint to us young 'uns, there were four lads picked out of our corps to assist in this piece of duty, myself being one of the number chosen.

Besides these men, four soldiers from three other regiments were ordered on the firing-party, making sixteen in all. The place of execution was Portsdown Hill, near Hilsea Barracks, and the different regiments assembled must have composed a force of about fifteen thousand men, having been assembled from the Isle of Wight, from Chichester, Gosport, and other places. The sight was very imposing, and appeared to make a deep impression on all there. As for myself, I felt that I would have given a good round sum (had I possessed it) to have been in any situation rather than the one in which I now found myself; and when I looked into the faces of my companions, I saw, by the pallor and anxiety depicted in each countenance, the reflection of my own feelings. When all was ready, we were moved to the front, and the culprit was brought out. He made a short speech to the parade, acknowledging the justice of his sentence, and that drinking and evil company had brought the punishment upon him.

He behaved himself firmly and well, and did not seem at all to flinch. After being blindfolded, he was desired to kneel down behind a coffin, which was placed on the ground, and the Drum-Major of the Hilsea dept, giving us an expressive glance, we immediately commenced loading.

This was done in the deepest silence, and, the next moment, we were primed and ready. There was then a dreadful pause for a few moments, and the Drum-Major, again looking towards us, gave the signal before agreed upon (a flourish of his cane), and we levelled and fired. We had been previously strictly enjoined to be steady, and take good aim, and the poor fellow, pierced by several balls, fell heavily upon his back; and as he lay, with his arms pinioned to his sides, I observed that his hands waved for a few moments, like the fins of a fish when in the agonies of death. The Drum-Major also observed the movement, and, making another signal, four of our party immediately stepped up to the prostrate body, and placing the muzzles of their pieces to the head, fired, and put him out of his misery. The different regiments then fell back by companies, and the word being given to march past in slow time, when each company came in line with the body, the word was given to "mark time," and then "eyes left," in order that we might all observe the terrible example. We then moved onwards, and marched from the ground to our different quarters. The 66th stopped that night about three miles from Portsdown Hill, and in the morning we returned to Winchester. The officer in command that day, I remember, was General Whitelock, who was afterwards brought to court-martial himself. This was the first time of our seeing that officer. The next meeting was at Buenos Ayres, and during the confusion of that day one of us received an order from the fiery Craufurd to shoot the traitor dead if he could see him in the battle, many others of the Rifles receiving the same order from that fine and chivalrous officer.