James Laver - Fashions and Fashion Plates 1800-1900

Here you can read online James Laver - Fashions and Fashion Plates 1800-1900 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: Read Books Ltd., genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Fashions and Fashion Plates 1800-1900

- Author:

- Publisher:Read Books Ltd.

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Fashions and Fashion Plates 1800-1900: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Fashions and Fashion Plates 1800-1900" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Fashions and Fashion Plates 1800-1900 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Fashions and Fashion Plates 1800-1900" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

FASHION PLATES

Victoria & Albert Museum

THAT everybody is now fashion-conscious to a degree which a few years ago would have been thought incredible is due less perhaps to the innumerable books on the history of costume which have been published during recent years than to the influence of the films. It is true that the producers of historical films still sometimes make grave blunders, but on the whole they do their best to get things right, and some of the larger companies have permanent staffs of experts and extensive libraries of material. That is one of the reasons why fashion plates are becoming rarer and rarer. Many thousands have made their way to Hollywood, and our only consolation must be the prospect of seeing them come to life before our eyes, to see this favourite or that simpering in the robes of the forties or sweeping majestic in voluminous draperies through the salons of the Second Empire.

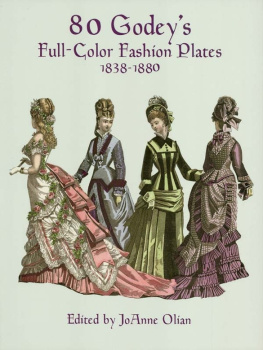

Fashion plates are almost exclusively a nineteenth-century thing, which is one reason for limiting the present survey to that period. They hardly exist before the French Revolution; by 1900 they have been replaced by mechanical reproductions which have none of the charm of the genuine fashion plate.

The fashion plate properly so-called is an etching, or a line engraving, or a lithograph, coloured by hand, and some of the best reach a very high degree of aesthetic value. Many of them are to be found in the ladies magazines which made their sudden appearance in the last years of the eighteenth century, the notion that women could want a magazine devoted to their own interests being then a very revolutionary idea indeed. One of the earliest of such journals was The Ladys Monthly Museum, which came out first in 1798. It soon had rivals in Le Beau Monde and La Belle Assemble, and the last contains, for the first twenty or thirty years of the nineteenth century, some of the best fashion plates ever published. The Englishwomans Domestic Magazine belongs to a later period. It has all the improving characteristics of the early Victorian age, but it is still a valuable reflection of the frivolities of fashion. In later journals such as The Young Englishwoman we find rumours of emancipation and even hints of something called the Vote, but they still have fashion plates. It is curious to note that about the middle of the century most of the English fashion magazines gave up trying to produce their own plates or even to copy those of France. They contented themselves with importing French plates from such papers as Le Follet, Courrier des Salons, sometimes not even troubling to re-engrave the titles. The leading French journals were Le Moniteur de la Mode, Les Modes Parisiennes, Le Journal des Demoiselles, Le Petit Courrier des Dames, and Le Magazin des Demoiselles, and the plates which they issued are among the best that have ever appeared. The principal artists were Hlne Leloir, Compte Calix, and Anas Toudouze, and as Mr. Vyvyan Holland, the well-known collector of fashion plates, has remarked, they all seem to have worked steadily from the forties until almost the end of the century. Anyone who wishes to collect fashion plates would do well to keep his eyes open for these three names, which can often be found scrawled inconspicuously in the corner of the engraved surface, half hidden among the arabesques of the design.

We have said that the rise and fall of the fashion plate was one of the reasons for limiting the present study to the period of the nineteenth century. But the century is easily treated as a whole when we come to consider costume itself. It is in vain that we are told that this habit of dividing time into centuries is a mere trick of the mind. The centuries do seem to have an individuality of their own, and the nineteenth is no exception. It is as if the Time-Spirit, feeling the end of the eighteenth century approaching, looked about him for some new style, fit, with all its minor variations, to clothe mankind and womankind during the next hundred years. He was weary of hoops and paniers and embroidery, tired of wigs and powder and knee-breeches and buckled shoes; tired most of all of that three-cornered hat which had been the one possible type of headgear since the Age of Anne. He resolved to make all things new.

He was singularly helped in this endeavour by the French Revolution. By that deliberate and far-reaching break with the past, it would have been strange if clothes had not been affected. But no break with the past can be complete. It is impossible to invent something absolutely new, especially in clothes, and the cry of Back to Nature, which is always raised in revolutionary epochs, cannot mean Back to woad and a few bangles. So Frenchwomen, when they abandoned the clothes of the Ancien Rgime, went back to what they fondly imagined were the modes of ancient Greece, and Frenchmen, discarding their embroidered coats and high-heeled shoes, adopted a modified version of the attire of the English country gentleman.

It will be convenient to deal with the men first. It may seem strange at first that they were so much less drastic in their reforms than women, but there are various reasons for this. First, mens dress is always more conventional than womens and fashion plays a much smaller part in its development. Second, the writings of Rousseau and others had turned mens thoughts and admirations to country life. But the English gentleman already lived in the country and he had already adopted country clothes. He had changed his embroidered silk for a coat of plain broadcloth, his shoes and silk stockings for stout boots reaching to just below the knee. He had changed his hat also, and this hat of his is of sufficient importance to linger over for a moment; for the changes he had made in it were destined to have far-reaching results.

In riding to hounds, which was his favourite occupation, he found that the wind was apt to catch the wide brims of the tricorne and blow it off his head. He accordingly made the brim very small. Then when he was thrown from his horse, which frequently happened, he found that it was a great advantage to have a hat with a high crown. It acted as a kind of primitive crash-helmet. Shrink the brim and raise the crown and you transform the three-cornered hat into a top-hat and the typical headgear of the eighteenth century gives place to the typical headgear of the nineteenth. So far as men are concerned, the nineteenth century could be called the century of the top-hat.

Another important innovation, in mens attire, was also due to the hunting field. The wide full skirts of eighteenth-century coats were inconvenient on horseback. So they were cut away at the front either by tapering them awayin which case we have the ancestor of the morning coator by cutting out a square slice just below the waistin which case we have the prototype of what we now call full evening dress. It is curious to reflect that the modern tail-coat is really a riding costume, and what we still imply on the rare occasions when we now put it on is: I am an English country gentleman; my real passion is riding to hounds. Almost to the middle of the nineteenth century the cut-away coat was not necessarily an evening garment at all. It was worn in the daytime, for people still remembered that it was originally a sports costume and was properly worn only with top-boots.

By 1800 the main lines of mens costume for the next hundred years were already laid down. Coats were of plain cloth. As therefore the only distinction possible was excellence of cut, the rise of English tailoring may be dated from this period. The Regency dandy was, by comparison with the Macaroni of the previous century, very plainly dressed, but his clothes fitted without a wrinkle. The silk hat was not yet invented, but the high-crowned beaver already sat upon a head which had lost both wig and powder, although lawyers and clergymen kept the wig and footmen the powder for some years longer. Lace ruffles had given place to plain wrist-bands. The neckcloth, however exaggerated its convolutions, is plainly the ancestor of the modern neck-tie. One thing alone is missing, and to us who see the nineteenth century in retrospect its lack is startling. Men did not yet wear trousers!

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

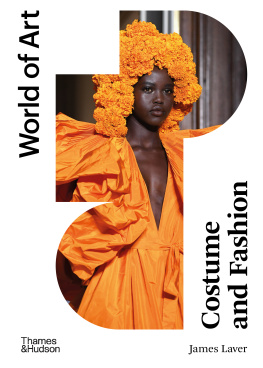

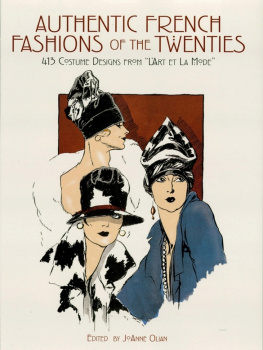

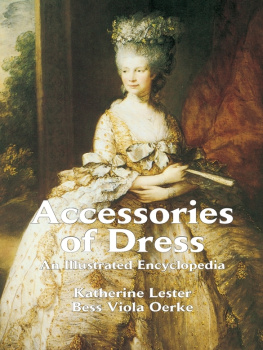

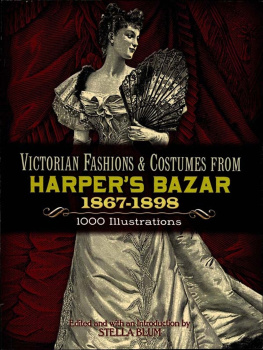

Similar books «Fashions and Fashion Plates 1800-1900»

Look at similar books to Fashions and Fashion Plates 1800-1900. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Fashions and Fashion Plates 1800-1900 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.