Contents

Page List

Guide

If You Cant Quit Cryin, You Cant Come Here No More

by Betty Frizzell

Copyright 2021 by Betty Frizzell

All rights Reserved.

ISBN:

eISBN: 9781627311052

Feral House

1240 W Sims Way #124

Port Townsend WA 98358

www.feralhouse.com

Cover Design: Lissi Erwin/Splendid Corp.

Layout: Ron Kretsch

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

If You Cant Quit Cryin, You Cant Come Here No More

A Familys Legacy of Poverty, Crime and Mental Illness in Rural America

BETTY FRIZZELL

Dedication

This book is dedicated to Mom, Vicky, Julian, and the love of my life, Gary Wedge Thompson.

CONTENTS

Mom, Vicky and me, Poplar Bluff, Missouri, 1980

M om wouldnt hold me like the mothers I saw on television. She didnt like to be touched or touch anyone else. She would say, Stop that. You are all right, with maybe a slight pat on the back if I fell down or experienced one of the many emotional bruisings that cause kids to cry. After years of getting no response from Mom to my crying, I conditioned myself to cry silently and later not to cry, or for that matter, to not show emotion in any circumstance. However, since May 12, 2013, I have cried more than at any other time in my life.

As my then-husband Jimmy turned off the ten oclock news, I realized my older sister, Vicky, hadnt called today. She lived 150 miles south of St. Louis in Puxico, Missourithe bootheel of the state. Vicky didnt use social media or texting, so phone calls were our primary communication. I sat in bed and knew I couldnt sleep until I spoke to her. I called her. The phone rang, and her 30-year-old son, Kenny, answered.

Wheres Vicky at? I said.

Where the hell do you think she is? Shes in Stoddard County Jail, he replied. What for? I asked.

She killed Chris. He replied as if my sister murdering her husband was common knowledge, something I shouldve already known.

I hung up and screamed at Jimmy to get me the number for Stoddard County, Missouri Jail. He bolted straight up in bed.

Why do you need the number for? Whats going on?

Vicky killed Chris. Those words slipped out of my mouth, but they werent my words. Someone in my body was saying them. I didnt want to own them.

What? What happened?

I stood there dialing the jail number and hoping Kenny was wrong. Yes, do you have an inmate named Victoria Isaac? I asked.

Yeah. We have Victoria Isaac, the voice on the other end said.

Whats she in jail for? I asked, praying it was for anything but murder.

First-degree murderno bond.

My legs went out from under me. As I sat stunned on the floor, Jimmy took the phone to speak to the deputy working the late-night shift answering calls. My heartbeat thrummed in my ears. I couldnt see the room through my tears.

Calm down, honey. Calm down. Jimmy, always with high anxiety, couldnt stop talking. He went across the hallway and woke up my teenage son, Julian. Jimmy and Julian were speaking to me, but our world was stuck in slow motion. I was a cop down to the tips of my toes and as part of my police training, I understood how adrenaline works and how time stops during extreme stress. But this was my sister, not some random call from someone I didnt know. I felt dissociated from my own body, and I heard, again and again, ringing throughout my scattered and shattered thoughts, my mothers deathbed request to me: Take care of Vicky and Kenny because they aint right.

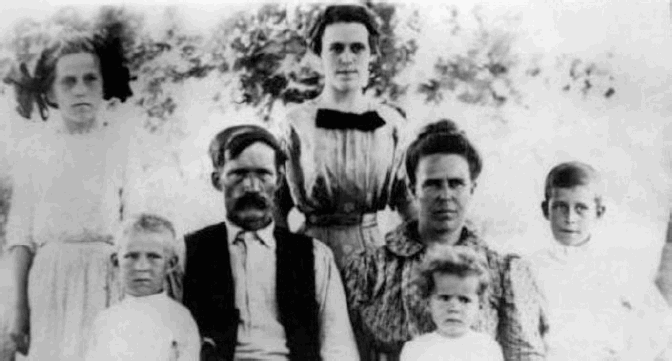

The Frizzell family. Back Row: Vesta and Victoria Middle Row: Oscar, Grandpa Leander, Grandma Lottie, Jessie Front: Roxie.

V icky isnt the first person in my family to be charged with felony murder. Murder is generational in our family. The Frizzells were known for two things: musical talent and quick tempers. Mom would describe her kin as the kind of people who would rather shoot you than look at you. They played old-time country music as feverishly as they fought. As a child, I watched Grandma Roxie play the guitar with her brother Toots who played the left-handed fiddle while Aunt Lottie occasionally accompanied on the autoharp. My great-grandfather, Lee Frizzell, was the thirteenth of fourteen children born in Putnam County, Ohio. Lee married Lottie Carles in 1894 and started a family. Six years later, Lee moved the family in a covered wagon from northwestern Ohio to southeast Missouri. Lee and Lotties seventh child, my grandmother Roxie, was born as the family crossed the Black River. They settled outside of Poplar Bluff, Missouri, on a plot of land near that very same river.

An old family story tells how a Black family with two small children, a boy and a girl, moved downriver from the Frizzell homestead. The children would play on the logs cut down to make the familys cabin and often strayed onto great-grandfathers land. Lee repeatedly told them to stay on their own property. One day, Lee and my elementary-school-aged grandmother Roxie saw the two children playing inside a hollowed-out log on a hill near the waters edge. Lee told Roxie to hide behind a tree while he took care of them once and for all. He waited for the children to climb inside the log, then pushed the log down the hill and watched as it rolled into the water. With her hair ribbons blowing in the wind, Roxie stood silently as Lee walked to the rivers edge and held that log, with the children trapped inside, under the water until the bubbles and water splashing stopped. Their parents would find the two bodies floating in the dark river a few hours later. Lee never denied or admitted causing their deaths. The police did not investigate. Thats the kind of man he was.

Roxie lived with violence and had developed a taste for it as she grew older. An incident in February 1922 turned her heart as cold and dark as the Black River. Her older brother Jessie was deep in the woods making illegal alcohol. A man attempted to rob him. A fight ensued, but Jessie got free and ran toward the familys small cabin. Roxie, who had been out in the woods shooting squirrels, saw her brother running along the path. He told her to stop the man chasing him while he ran to get their father.

She stood silently behind a tree, wrapped her small hands around the gun, and fired a shot into the unknown pursuer. The man lay bleeding on the ground. Roxie held the gun over him until the brother and father arrived. Lee told her to go home and they would take care of the matter. No word was ever spoken about the incident. Days later, Roxie read a newspaper article that reported that a mans torso had been found floating in Black River and that the arms and legs had been severed clean off. The head was also missing and later discovered a short distance downriver. It, too, was maimed beyond all recognition.

Great-Uncle Lee (Toots), Grandma Roxie and me in 1981

You could say that homicidal ideation seemed to be genetic as the thread of violence running through the Frizzell bloodline was present in all my great-uncles, aunts, mother, and siblings. Roxies older brother, my great-uncle, also named Lee, was arrested for murder on June 18, 1969. That night Lee had laid down in his bedroom to nap after a bout of heavy drinking. The noise of his step-grandchildren woke him. He loaded a gun and began randomly shooting through the closed door into the front room. His 17-year-old step-granddaughter was left dead, and his 13-year-old step-grandson was injured. He was charged with first-degree murder and sent to a psychiatric institution for three years. Her sister, Victoria, was infamous in Poplar Bluff. She was a madam who ran the establishment called House of the Pleasurable Ladies. Another great-uncle, James, disappeared after being implicated in a series of murders in Washington state. He was never seen or heard from after that.