1

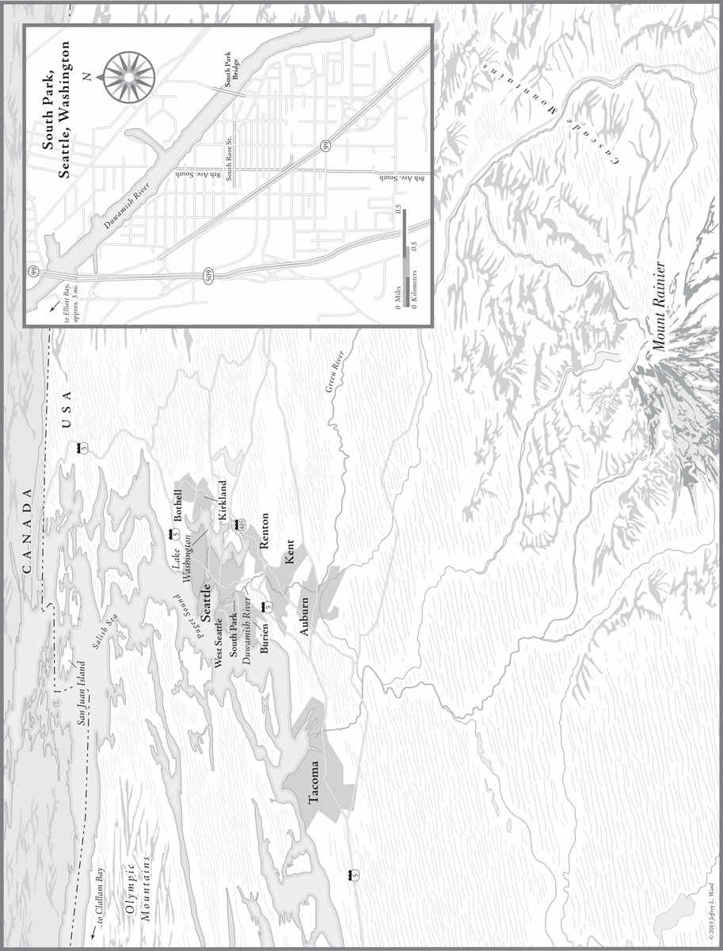

O n old maps, the Duwamish River bends like discarded ribbon as it passes through a valley on the southern end of this city, winding across land that was once marshes and tribal fishing villages and then emptying into the salt water of Elliott Bay. Melt from nearby mountains carved this path, rich with salmon that fed the Duwamish Indians in the years before their last unfettered chief, Siahl, learned his name would be hammered by white settlers into the name of a new American city: Seattle. Not long afterward, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers showed up and spent a few years straightening and deepening the Duwamish for the purposes of large-scale commerce. Now the river looks more like a ribbon pulled taut.

Heavy industry lines its sides, dingy barges fill its moorings, and its last five miles have been declared a federal Superfund mega-site, so thick with PCBs, mercury, and arsenic that eating anything that lingers here is inadvisable. This is Seattles only river. At whats been called its dirty mouth sits a mammoth artificial island built from dredged Duwamish silt: flat, paved over, and planted with tall orange cranes for unloading shipping containers at the international port. Upriver, toward the other end of the Superfund stretch, is a shallow bend that seems an homage to an earlier time, and tucked in the crook of this bend, across from a former Boeing plant where World War II bomber production helped begin the rivers fouling, is the neighborhood of South Park.

In the summer of 2009, the best way to reach South Parks main strip of taqueras and tire shops was by crossing an ailing drawbridge over this bend in the Duwamish. The decks of the bridge swelled in summer heat so that opening and closing became impossible. Its two halves, and their identical brick watchmens houses, were drifting in opposite directions. Its support pilings failed to find solid purchase beneath the toxic river-bottom muck. As a consequence, the South Park Bridge ranked as one of the least safe spans in the state.

Near the riverbank where one of the bridge decks descended into the neighborhood, on the wall of a bar called the County Line, a hand-lettered sign urging downtown politicians to do something other than the stated plan, which was to close the bridge and let residents find other ways into the neighborhood. The back route, for example, along a highway that, like the Duwamish, faintly bends as it passes by.

The land between the damaged river and the rushing highway is equal to about one square mile, a confined space steeped from its first platting in cycles of need and neglect. In the years after the Duwamish people were dispossessed, and around the time the river was being straightened, this land was farmed by Italian and Japanese immigrants who cleared the camas plants and seeded its soil with radishes, spinach, peas, and mustard greens. In search of a venue for selling their produce, these farmers helped build the Pike Place Market in downtown Seattle. In need of a bridge across the Duwamish to help get their vegetables to town, and in need of electricity and fresh drinking water, too, they petitioned to be annexed by the young city and in 1907 got their wish. South Park became part of Seattles southern edge, and a rotting trolley bridge linking it to the other side of the river was torn down, replaced by a new bridge built from timber trestles and a plank deck. It didnt hold up long.

In 1931, another attempt at connection: the steel-beamed South Park drawbridge. Owing to time, inattention to upkeep on the part of downtown power brokers, and an earthquake that rattled its crumbling concrete at the start of the new century, this bridge presented by 2009 a dangerously decayed visage, demoralizing and perfectly aligned with the economic moment, all busted potential and uneven openings.

Closure without remedy was not acceptable to South Parks four thousand residents, by now mostly Hispanic and mostly not speaking English at home. But their demand for a new bridge was a hard one to meet the year after a financial crash, the city budget tapped out, more people than usual showing up at the river with fishing rods, hungry, casting next to warning signs posted in Spanish, Laotian, Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, Russian. Complicating matters, a new bridge was not the residents only demand.

The people of South Park lived, for the most part, on a core of tree-shaded streets, many of them dead-ending at the river, or the highway, or the circumference of fenced lots that otherwise hemmed in the neighborhood, lots holding businesses like Cain Bolt & Gasket or Sound Propeller Services, lots that, when they didnt contain elemental companies in low industrial buildings, tended to hold giant spools of marine-grade rope, ship winches, metal buoys, all of it detritus washed up from the nearby port. On one inland corner of the neighborhood was something referred to by city signage as a transfer station, a delicate way of saying city dump. No one was asking for extravagant changes to this environment. The odors from the dump, the scents of creosote drifting in off the water, the taste of ammonia blowing through cement factory fences, the howl of jets on descent toward the airport, so close that conversations below had to pausesuch things came with the territory. But people who made their homes here did feel that in addition to a new bridge they deserved more police to patrol their roads, some of which appeared to be crumbling back into dirt, and better lighting so that fewer night shadows would be on offer along the main avenues, inviting unpredictable characters who trudged up from the ragged vegetation along the riverbank or wandered in from the budget motels and homeless encampments of the surrounding industrial netherland. It was hoped as well that better sewage and drainage pipes might someday stem the flooding that swamped many South Park basements when rains came down heavy, sending rats and spiders scurrying for higher ground.

All of this would likely have to wait and, if history was any guide, might well be forgotten amid demands from other neighborhoods that were not majority Hispanic, and working class, and from a trammeled river delta. It had always gone this way. So people in South Park had learned to counter inevitable disappointment with reeled-in expectations. With patience, too, when possible, sometimes helped along by a measured pleasure at the way South Parks neglect, in a familiar paradox, made the neighborhood. Made it one of Seattles most diverse communities. Made its homes a bargain during the boom years. Made its food affordable and filling. Made it clear to those living along the botanically named residential streetsThistle, Elmgrove, Rosethat they should not expect outsiders rushing in to make things better, that instead the mix of languages and ethnicities within this one square mile would have to get by on their own. Which meant together.