First published in 1933 by G.P. Putnam's Sons

This edition first published in 2018 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1933 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Publisher's Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

A Library of Congress record exists under ISBN: 33027210

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-55387-3 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-203-70471-4 (ebk)

THE LIFE OF CSAR

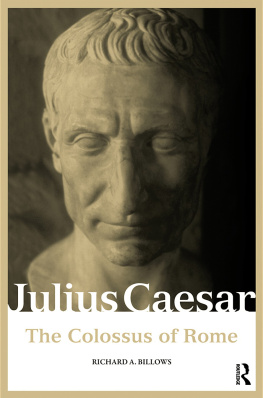

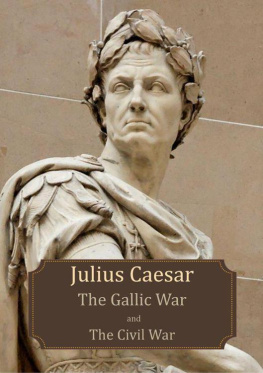

This bust was formerly thought to be a contemporary bust of Csar, but is now known to be a comparatively modern work

Reproduced by kind permission of the Trustees of the British Museum

THIS book is the anti-fascist, or, if the reader prefers, the anti-bolshevist history of Julius Csar. He need not be alarmed; he will not be asked to read a political pamphlet. This history of Julius Csar was written thirty years ago in 19001901, when the words "Fascism" and "Bolshevism" had no political meaning for the world in general. The present edition, which an enterprising publisher is offering to the public, only differs from the original in that certain abridgments have been made and the copious notes of the first edition omitted.

How was the author able to write an anti-fascist or anti-bolshevist history of Julius Csar at a time when Fascism and Bolshevism did not exist? That is what will be explained in this preface.

The nineteenth century thought of Julius Csar mainly as the destroyer of the Republic and the founder of the Empire. Civil war and dictatorship were the crown of his achievement. He had striven all his life to bring about the dictatorship; to replace the "parliamentary" government of the aristocracy and the Senate by the despotism of genius; to invest the Empire with monarchical institutions which were to assure it three centuries of peace, order, prosperity and greatness. He had understood that republican oligarchy had run its course, that the world had need of a strong monarchical power; and he had hastened the pace by a masterly and successful stroke. Praise to his immortal genius!

This is the thesis which was developed by the most famous historians of Csar in the nineteenth century, such as Drmann, Mommsen and Duruya thesis which was currently accepted.

When I resumed my study of Roman history at the end of the nineteenth century, I quickly discovered that this supposed history of Julius Csar was only a romance. The Roman Empire in the first two centuries of our era was not a monarchy, either in the ancient or in the modern conception of the word. Csar did not destroy the Republic or create the imperial government; the latter was the slow creation of several generations who owed nothing of their achievement to Julius Csar. Csar never intended to seize the supreme power for himself; civil war was only an accident provoked by the hatred of his enemies and not by his ambition. It ended by placing him, his enemies, the whole Republic, in an inextricable position, and instead of putting an end to the crisis with which the Republic was contending, it complicated matters still further. If Csar occupies a great place in history, it is not because he destroyed the Republic and founded the Empire, but because he conquered Gaul. The conquest of Gaul was the beginning of European history.

But how was it that a young man of thirty could so easily overthrow the historical tradition of an entire century without being treated as an iconoclast, that he could even rouse sympathy? It was because towards 1900 the passion which had inspired the great romantic misrepresentations of Drmann, Mommsen and Duruy had died down. What was this passion? The admiration of that creation of romanticism, the hero-usurper and the saviour-tyrant. After 1830, when the generation which had known the horrors of the Napoleonic rgime began to die out and to forget, the tyrant of genius became popular in every quarter. In conservative circles he was regarded as an antidote to the liberal and democratic tendencies of the middle and lower classes; in liberal circles, as a weapon against traditional monarchy, the principle of heredity and respect for the old classes. In their enthusiasm for the tyrant of genius, for the hero-usurper, it was not enough to create one such figure and place it at the threshold of the nineteenth century, like a tutelary deity; they had to look about for precursors. So they manufactured a Csar, the elder brother of Napoleon, whom the ancients would not have recognized.

When this romantic passion had calmed down a little, towards 1900, many people allowed themselves to be convinced by the new version of Csar. The transfiguration of Csar should have been followed by an analogous transfiguration of Napoleon whose figure has been even more distorted than that of Csar; and both should have helped to free our generation from the fatal poison of nineteenth-century political romanticism, source of revolutions and reactions equally absurd,

But the World War intervened, and after the war came the revolutions which ended in so many countries with despotic usurpations by individuals or groups. These usurpations have everywhere awakened the old romantic illusion of the saviour tyrant. Even in privileged countries living under a legitimate government, there are many people who turn to Moscow or Rome, wondering whether a coup de main suppressing discussion and control of the government would not be the quickest and safest remedy for the ills of the world. Everywhere people are again beginning to falsify the history of Julius Csar and of other personages who might incarnate the romantic type of the hero-usurper. Almost all the books on Napoleon published since 1919 will count among the worst examples of historical writing of recent times. Formerly, an effort was made to present a Napoleon who would at least appeal to the imagination of the deluded but cultured few; to-day, he is a hero-usurper for typists and cooks.