CAESAR

By the same author

THE GREEK DISCOVERY OF POLITICS

THE POLITICAL ART OF GREEK TRAGEDY

CAESAR

CHRISTIAN MEIER

Translated from the German

by David McLintock

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

i. Portrait head of Caesar from Tusculum in Turin.

2. Colossal portrait head from the 2nd century AD, Archaeological Museum, Naples.

3. Portrait head in green slate from the early 1st century AD, Pergamonmuseum, Berlin.

4. Portrait head of Caesar from Pisa.

5. Coin of Gaius Cassius Longinus commemorating the Roman secret ballot c. 126.

6. Coin of Lucius Cassius Longinus showing a citizen casting his vote, c. 63 B C.

7. Coin of Quintus Pompeius Rufus depicting a portrait of Sulla, c. 54 BC.

8. Augustan copy of a portrait head of Pompey from the 1st century BC.

9. Supposed portrait of Marcus Licinius Crassus from the Torionia Collection, Rome.

io. Diagram showing the supposed arrangement of the senators' seats in the curia.

ii. Inscribed 1st-century bust of Marcus Porcius Cato, modelled on a contemporary portrait, Archaeological Museum, Rabat.

12. Coin of Publius Nerva depicting a voting scene.

13. Copy from the imperial period of a mid 1st-century BC portrait of Marcus Tullius Cicero, Capitoline Museum, Rome.

14. Diagram of Pompey's theatre and colonnade based on the reconstruction in the Museo della Civilta Romana, Rome.

15. Coin of Lucius Hostilius Saserna celebrating Caesar's military successes.

16. Coin struck in the Pompeian army (46-45 BC) commanded by Pompey's son Gnaeus.

17. Portrait of Cleopatra VII on a coin struck in Alexandria c. 40 Bc.

18. Egyptian portrait bust in green slate of Mark Antony from the i stcentury B c, from Kingston Lacey, Dorset.

r9. Diagram of the Forum Julium based on a reconstruction in the Museo della Civilta Romana, Rome.

20. Coin of Marcus Mettius struck in 44 B c depicting Caesar Dict[ator] quart[o].

21. Coin issued in the Antonian army c. 33 BC.

22. Representation of the Curia Julia on a coin struck c. 30 BC.

23. Coin of Gaius Cossutius Maridianus struck in 44 B c showing Caesar as parens patriae.

24. Coin of Lucius Aemilius Buca from the year 44 BC showing Caesar as Dic[tator] perpetuo.

2S. Marcus Junius Brutus on a coin struck by Lucius Plaetorius Cestius from the army of Caesar's assassins, commanded by Brutus, c. 43-42 BC.

26. Coin struck in Brutus' army commemorating the Ides of March c. 43-42 BC.

Due to circumstances beyond their control the Publishers have been unable to acknowledge all the photographic sources for the illustrations used in this book. They will be happy to do so in future editions if they are notified.

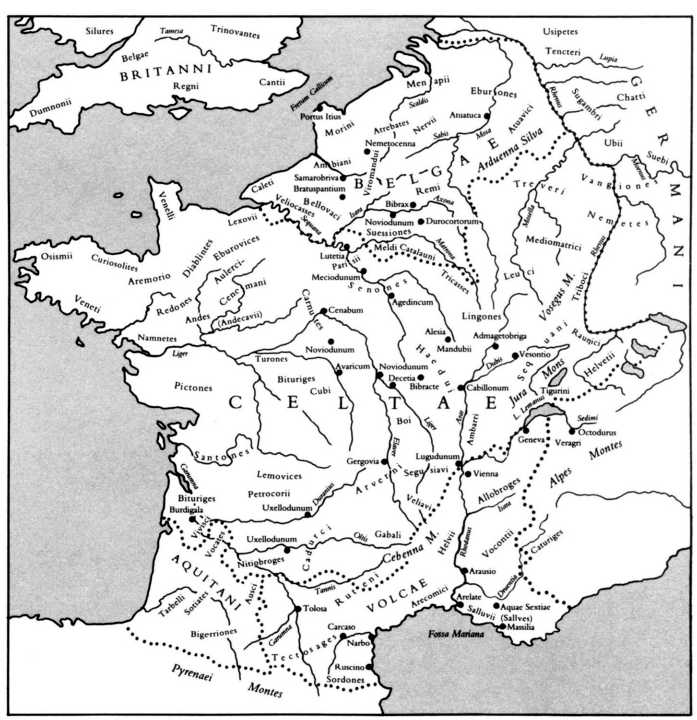

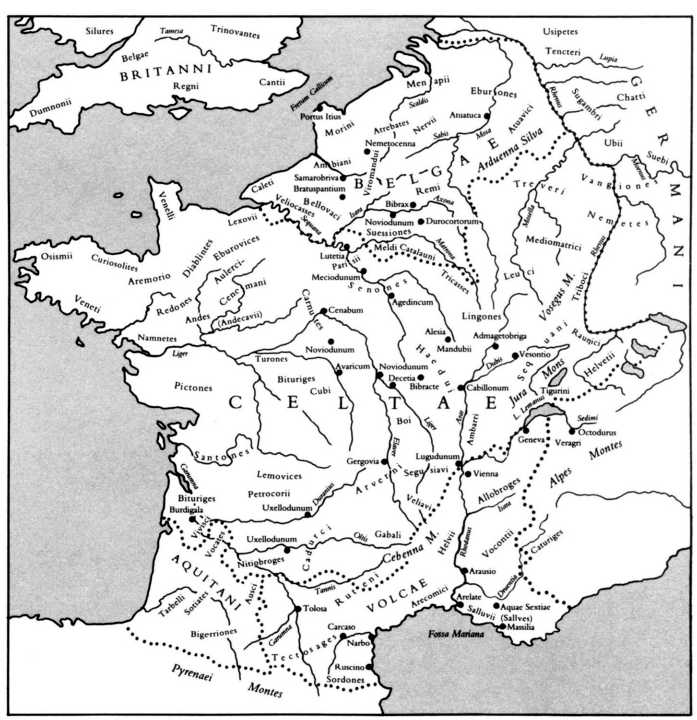

Gaul at the Time of Caesar

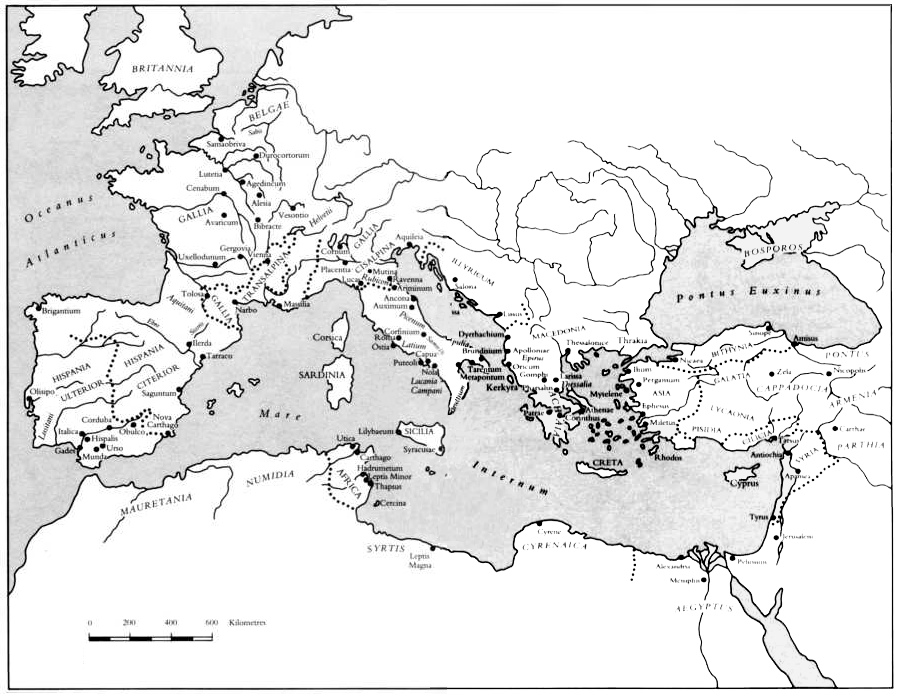

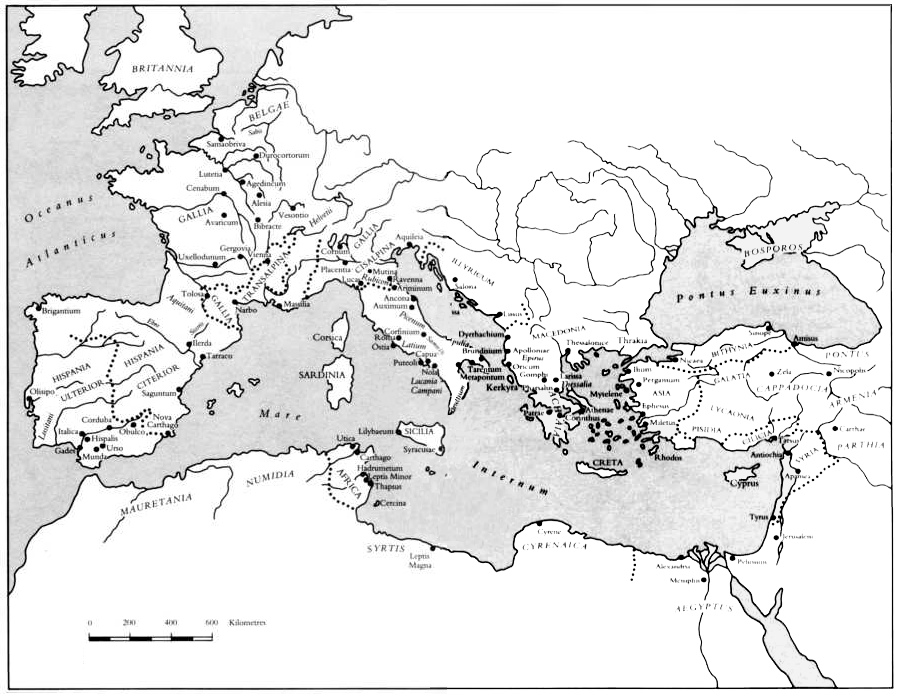

The Roman World at the Time of Caesar

1

Caesar and Rome

Two Realities

THE SENATE DECLARES A STATE OF EMERGENCY CAESAR AT THE RUBICON THE MONSTROUS CAUSE OF THE WAR THE POSITIONS OF THE PARTIES TWO REALITIES

N I JANUARY 4 9 B C the consuls began to do everything in their power to remove Caesar from his governorship. He had held it for almost ten years and its term had expired. Caesar now intended to seek the consulship for 48 and return to internal politics. This was just what his opponents wished to prevent. Before he could offer himself as a candidate he was to lay down his command and return to Rome as a private citizen. Once there, he was to be prosecuted for various breaches of the constitution of which he had been guilty during his previous consulship in 59 BC. It was clearly intended that this should take place under military protection, so that he would be unable to put pressure on the court, and also, no doubt, so that the court would not be entirely free from pressure in reaching its verdict. It seems to have been hoped that in this way Caesar's political existence could be destroyed and the power of the Senate regime fully restored. Irrespective of whether or not Caesar really was an opponent of the traditional order, he had persistently interfered with its proper functioning during his previous consulship. It was therefore to be feared that if he succeeded in becoming consul again he would push through various demands against the will of the Senate and thereby become so powerful that repeated conflicts and repeated defeats for the Senate could be foreseen.

N I JANUARY 4 9 B C the consuls began to do everything in their power to remove Caesar from his governorship. He had held it for almost ten years and its term had expired. Caesar now intended to seek the consulship for 48 and return to internal politics. This was just what his opponents wished to prevent. Before he could offer himself as a candidate he was to lay down his command and return to Rome as a private citizen. Once there, he was to be prosecuted for various breaches of the constitution of which he had been guilty during his previous consulship in 59 BC. It was clearly intended that this should take place under military protection, so that he would be unable to put pressure on the court, and also, no doubt, so that the court would not be entirely free from pressure in reaching its verdict. It seems to have been hoped that in this way Caesar's political existence could be destroyed and the power of the Senate regime fully restored. Irrespective of whether or not Caesar really was an opponent of the traditional order, he had persistently interfered with its proper functioning during his previous consulship. It was therefore to be feared that if he succeeded in becoming consul again he would push through various demands against the will of the Senate and thereby become so powerful that repeated conflicts and repeated defeats for the Senate could be foreseen.

For almost two years Caesar's dedicated opponents had sought to persuade the Senate, Rome's central organ of government, to relieve him of his command. They had repeatedly failed because Caesar had won over some of the tribunes of the people, who could use their right of veto to impede any resolution the Senate passed against him. At times they even went on to the offensive and forced it to pass resolutions in his favour. For although the majority of the senators were opposed to the proconsul and desired a speedy end to his governorship, they were even more opposed to a civil war and, knowing that Caesar was not to be trifled with, were inclined to let him have his way.

At the beginning ofJanuary Caesar's opponents set all the wheels in motion to oblige the Senate to settle the matter once and for all. Supporters were drummed up, the alarm was sounded, and powerful sentiment aroused. The Senate resolved that if Caesar had not laid down his command by a certain date he would be acting against the republic. The tribunes of the people used their veto. Since they refused to yield, the Senate, on 7 January, passed the `extreme decree' (senatus consultum ultimum); this amounted to declaring a state of emergency.

The Caesarian tribunes of the people thereupon left the city, disguised as slaves, in one of the carriages that stood ready for hire at the city gates. (These conveyances, together with horses and litters, were the normal means of transport for lengthy journeys; the horses could be changed en route.) By doing so they indicated that the freedom of the Roman people was in such jeopardy that even its guardians, whom the people had once sworn to protect, were no longer assured of safety.

Caesar was at Ravenna, in the extreme southeast of his province of Gallia Cisalpina. On the morning of io January 49 (mid-November according to our calendar) a courier brought news of the Senate's decree and the flight of the tribunes. Without much ado Caesar at once sent a troop of soldiers towards Ariminum (Rimini), the first sizeable town in Italy proper, which lay beyond the Rubicon, the narrow river that bounded his province. It was an immensely bold decision, for Caesar had only one legion with him (five thousand foot and three hundred horse) - the bulk of his army was still in Gaul - but he wanted to take advantage of the element of surprise and hamper his opponents' preparations.

N I JANUARY 4 9 B C the consuls began to do everything in their power to remove Caesar from his governorship. He had held it for almost ten years and its term had expired. Caesar now intended to seek the consulship for 48 and return to internal politics. This was just what his opponents wished to prevent. Before he could offer himself as a candidate he was to lay down his command and return to Rome as a private citizen. Once there, he was to be prosecuted for various breaches of the constitution of which he had been guilty during his previous consulship in 59 BC. It was clearly intended that this should take place under military protection, so that he would be unable to put pressure on the court, and also, no doubt, so that the court would not be entirely free from pressure in reaching its verdict. It seems to have been hoped that in this way Caesar's political existence could be destroyed and the power of the Senate regime fully restored. Irrespective of whether or not Caesar really was an opponent of the traditional order, he had persistently interfered with its proper functioning during his previous consulship. It was therefore to be feared that if he succeeded in becoming consul again he would push through various demands against the will of the Senate and thereby become so powerful that repeated conflicts and repeated defeats for the Senate could be foreseen.

N I JANUARY 4 9 B C the consuls began to do everything in their power to remove Caesar from his governorship. He had held it for almost ten years and its term had expired. Caesar now intended to seek the consulship for 48 and return to internal politics. This was just what his opponents wished to prevent. Before he could offer himself as a candidate he was to lay down his command and return to Rome as a private citizen. Once there, he was to be prosecuted for various breaches of the constitution of which he had been guilty during his previous consulship in 59 BC. It was clearly intended that this should take place under military protection, so that he would be unable to put pressure on the court, and also, no doubt, so that the court would not be entirely free from pressure in reaching its verdict. It seems to have been hoped that in this way Caesar's political existence could be destroyed and the power of the Senate regime fully restored. Irrespective of whether or not Caesar really was an opponent of the traditional order, he had persistently interfered with its proper functioning during his previous consulship. It was therefore to be feared that if he succeeded in becoming consul again he would push through various demands against the will of the Senate and thereby become so powerful that repeated conflicts and repeated defeats for the Senate could be foreseen.