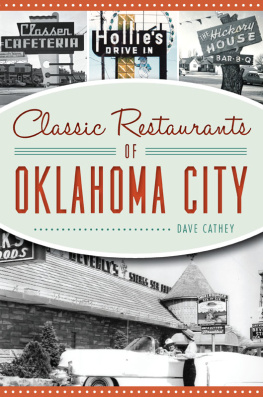

IMAGES

of America

OKLAHOMA CITY ZOO

19602013

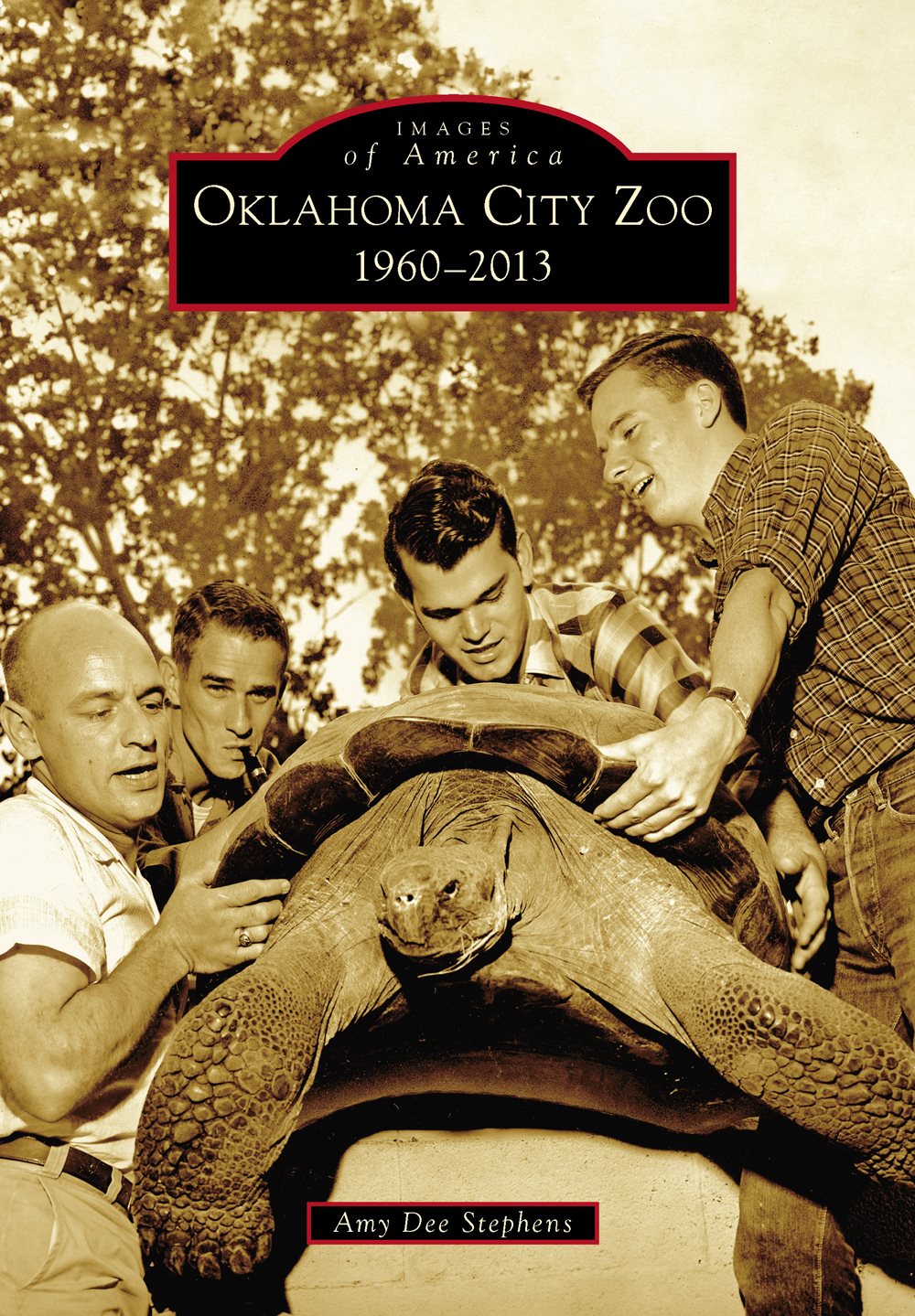

This book was inspired by a century of hardworking zoo employees. Each impacted the zoos future in innumerable ways. Many are featured in this book, and more deserve mention. The men in this photograph were zookeepers from the 1950s. Because of their efforts, and the employees who followed, a menagerie in 1902 grew to be a leading zoo by 2013. (Courtesy Patsy and Jimmie Stone, Oklahoma City Zoo Historical Archive.)

ON THE COVER: Zoo employees moved the Galapagos tortoises seasonally. From left to right, Bob Jenni, Russell Allen, Jess Harrison, and Tom Thorne relocate the large turtle to the summer pond on April 22, 1961. (Photograph by Cliff ?, Oklahoma Historical Society.)

IMAGES

of America

OKLAHOMA CITY ZOO

19602013

Amy Dee Stephens

Copyright 2014 by Amy Dee Stephens

ISBN 978-1-4671-1224-6

Ebook ISBN 9781439646823

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013958038

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

Dedicated to Donna Mobbs, administrative assistant to five zoo directors; and to my grandmother, Myrtle Davidson, who passed away during the writing of this book.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks go to zoo directors Bert Castro and Dwight Scott for supporting the historical efforts of the zoo and seeing its value; Dr. Teresa Randall, director of education, for allowing me the freedom to pursue this labor of love; Sherri Vance, ZooZeum archivist extraordinaire who has a deep understanding of community history; Jon Mays at the Oklahoma History Center, for allowing me access to unprocessed images; the late George Walters, for serving as unofficial zoo photographer from 1974 to 1992; the many volunteers who have assisted with newspaper article research; the Zoological Society; Tara Henson, Candice Rennels, and Carrie Allen in the zoos public relations department; Dr. Connie McCoy, Ernie Wilson, and Don Whitton, collectors of history; John Kirkpatrick and other visionaries who directed the zoos path; and my husband, Michael, for his encouragement and assistance with photograph selection.

Many more people deserve credit in this zoo history than could be mentioned. I selected stories and photographs that I thought represented favorite guest memories. Please know that every employee, volunteer, and patron who has walked through the gate has affected the course of the zoos future.

Unless otherwise noted, the images in this volume appear courtesy of the Oklahoma City Zoo Historical Archive (ZHA) and Research Division and the Oklahoma Historical Society (OHS), specifically photographs from the Oklahoma Publishing Company and the Oklahoma Journal.

INTRODUCTION

The community is very invested in the history of our zoo. Zoo memories are part of growing up in Oklahoma City.

Bert Castro, zoo director, July 2005

The Oklahoma City Zoo began in 1902 when a deer was donated to a park near downtown Oklahoma City. Eleven decades later, the zoo was a forerunner in animal care, exhibit design, and conservation. The story of the Oklahoma City Zoos development interweaves with the history of the city, national economy, and the diversity of people entering its gates. After 110 years, it was clear that although animals had the spotlight, the financial decision-making by the zoo and Zoological Society truly moved the zoo toward first-class status.

The zoo had humble beginnings. Local citizens donated native animals from around their homes to Wheeler Park. On September 7, 1903, the growing menagerie of animals was dedicated as Wheeler Park Zoo. The zoo relocated to a new site in 1924 and was renamed Lincoln Park Zoo. Economic challenges followed, but the community helped the citys parks department feed and pay for the animals care. Even during the Great Depression, citizens raised money to buy Luna the elephant, an effort that was repeated for Judy the elephant in 1949.

A key moment in the zoos development came during the 1930s, when the Civilian Conservation Corps and Works Progress Administration established work camps on zoo property. Many of their structures still existed into the 2010s, including the bathhouse, grottos, and the zoos amphitheater.

The city hired Leo Blondin as its first zoo director in 1930. He created a welcoming environment for families seeking to escape the hardships of the Depression. Blondins successor, Julian Frazier, excelled at developing fundraising campaigns to buy new animals. Children raised pennies to buy seals, giraffes, orangutans, Mathilda the hippopotamus, and the best-loved animal of the century, Judy the elephant.

The 1960s began a new era for the zoo, one that focused upon animal conservation and research. Although the circus-like atmosphere continued for a while, directors Dr. Warren Thomas and Phillip Ogilvie took a more serious approach to the zoo as a business. Both believed that guests should learn about the animals and that zoos might be the last hope for disappearing species. They began collecting large varieties of animals from around the world. The zoo, renamed the Oklahoma City Zoo, became famous for its hoofed animals.

The zoos nonprofit support group, the Zoological Society, formed in 1928. When philanthropist John Kirkpatrick was elected president in 1963, he surrounded himself with brilliant businessmen who provided financial advice and direction. Kirkpatrick is credited as having had the greatest impact on the zoos future, both financially and foundationally. Under his leadership, a plan was enacted to separate from the parks department, to operate under a public trust, and to accrue tracts of land while it was still available, all of which occurred over a 20-year period. As a result, the zoo grew to 550 acres, which prevented it from becoming landlocked like many other city zoos.

In 1975, the Zoological Trust was formed, comprised of trustees from the Zoological Society, the mayor, and city councilmen. Trust governance allowed the zoo to maintain city ties yet make financial decisions independent of government funding. Although Oklahoma City Zoo was not the first zoo to form a trust, it was one of the early zoos to do so, and the benefit was evident, as many zoos and museums looked to the zoo as a model into the 2010s. Such forward thinking during the John Kirkpatrick era allowed the zoo to grow, rather than just maintain operations.

Lawrence Curtis became zoo director in 1970. He embraced a new form of exhibit design that was more naturalistic. Curtis directed the opening of the zoos first habitat-themed exhibit, Condor Cliffs, followed by Galapagos Islands and the beginning construction of Aquaticus in the early 1980s. Working closely with the Zoological Society, over five million dollars was raised for Aquaticus, the zoos first major exhibit. Following the same formula, the zoo would tackle two mega exhibits per decade for the next 20 years.

After 15 years in Oklahoma City, Lawrence Curtis resigned and Steve Wylie took over for the next 15 years. Wylie formalized many of the zoos procedures and focused on exhibits that immersed the visitor in a habitat. He oversaw the zoos accreditation as a botanical garden, and visitors no longer described the zoo as red dirt and concrete but as lush and beautiful. The master plan that was developed under Wylie allowed for the upgrading of visitor amenities, from rides to restrooms. Taking a temporary step back from animal exhibits, the zoo expanded the education center and built a new entrance and indoor restaurant, which helped to accommodate the growing number of zoo visitorsnearly a million annually by the end of the 2000s.

Next page

![Waring Todd - Oklahoma City: [what the investogation missed-- and why it still matters]](/uploads/posts/book/242598/thumbs/waring-todd-oklahoma-city-what-the.jpg)