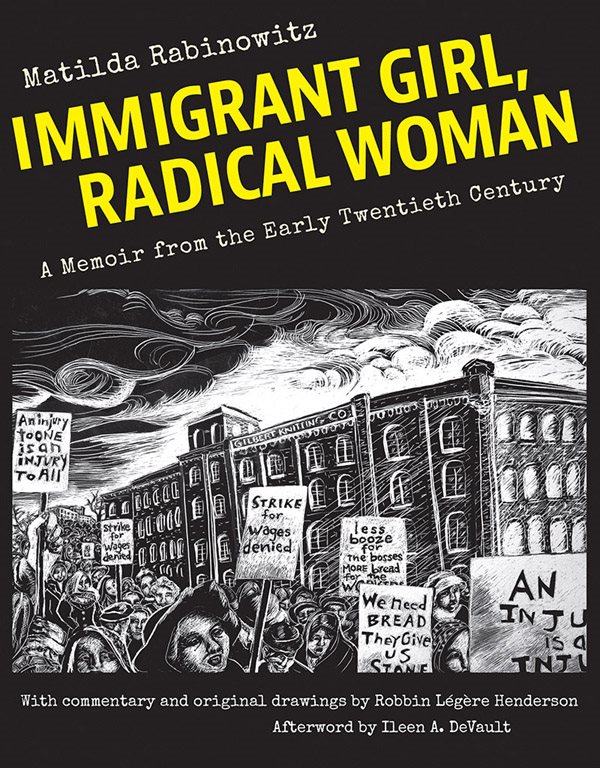

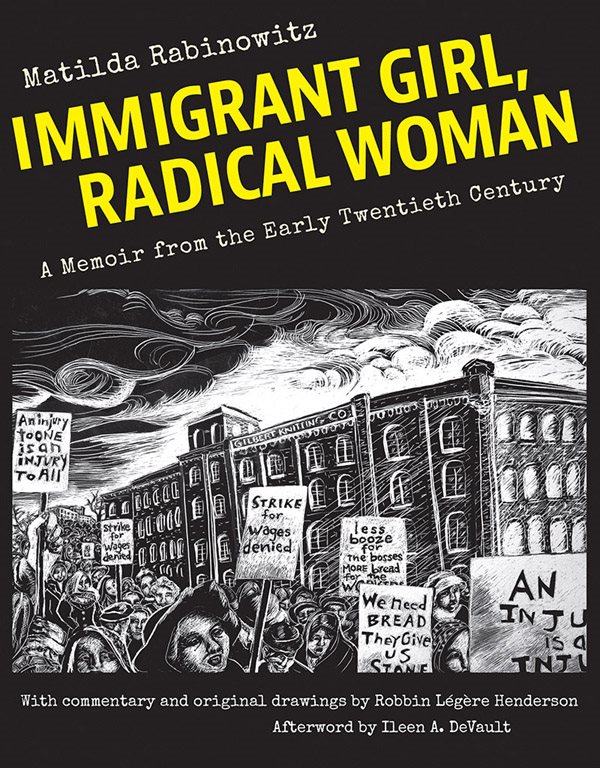

1THESE WERE PIONEERS, TOO

W hen my mother left the Ukraine with her five children to join my father in New York it was her third trip away from the small town of Litin where she and many generations of her forebears were born. Her first trip was to her husbands town, Shargorod, about 20 miles away, when she was a young bride. Her second trip was to a nearby town to which the family thought of moving, but didnt. And now to America.

The year was 1900. My father had been gone five years. He had spent a year in London. Then he moved on to New York and what he hoped was more opportunity to earn money and bring his family over. It took four years to scrape together enough to pay down one-half of the fare for one full and four half tickets (the youngest child being only five went free) from Russia to New York by fourth-class railroad and ship steerage. The other half, guaranteed by his lodge members, was to be met in weekly installments out of his future wages.

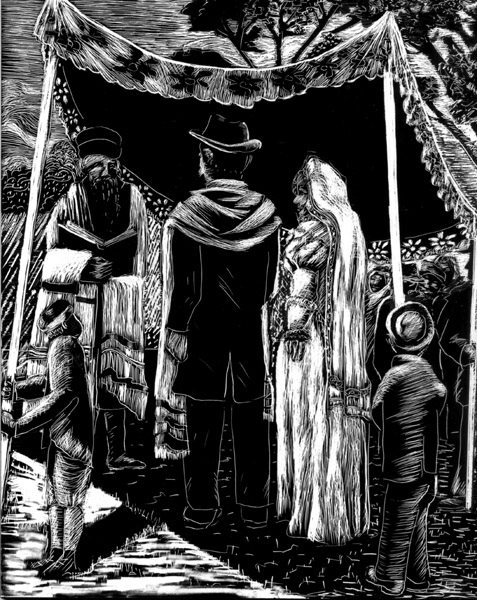

Naturally my mother was terrified at the prospect of traveling. The whole world was alien, and she was going to an alien land. But go she must. And so the day of departure arrived, a day of mourning. The family, the little town, the associations, for all the poverty and the cruelty of the Pale, had been all she had in life. Here she had been a young bride in a yellow silk dress, standing under the marriage canopy with her handsome groom. Here her children had been born. Many were the lean years. Great had often been her terror of persecution and pogrom, but it was the only home she knew. The only home we knew.

I was 12, the eldest. And once I, too, had made the journey to Shargorod to see for the first time my paternal grandfather and my step-grandmother. My fathers mother died when he was born.

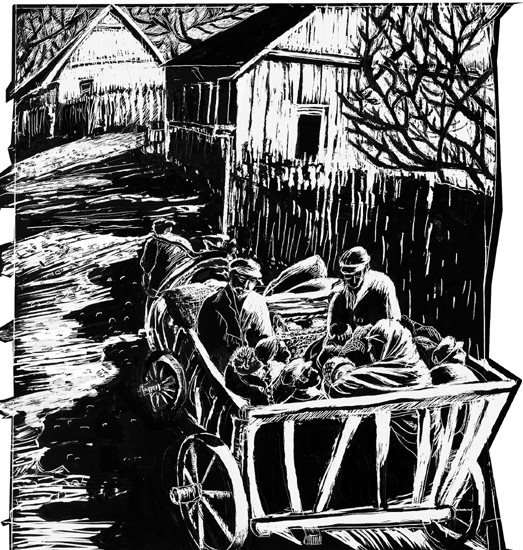

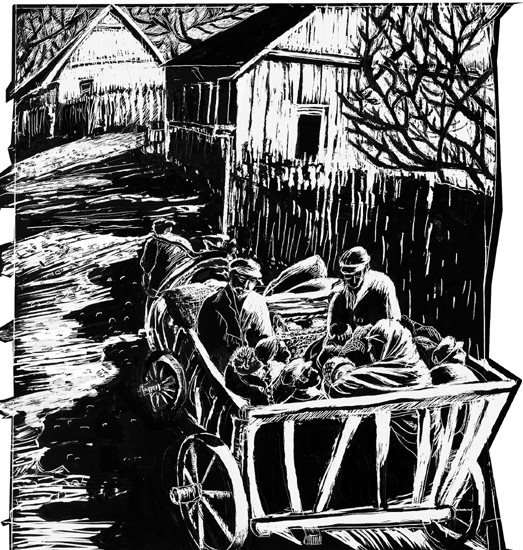

I remember the springless wagon and the clumsy lean horses. Three boards, slightly above the floor of the wagon, were fitted to its sides for seats. There was straw on the floor, and on the seats strips of old gray felt. I was the smallest passenger and in the charge of an adult acquaintance who was traveling somewhere beyond Shargorod. The wagon bumped over the rutty roads at about two miles an hour, and it took almost a day to make the journey.

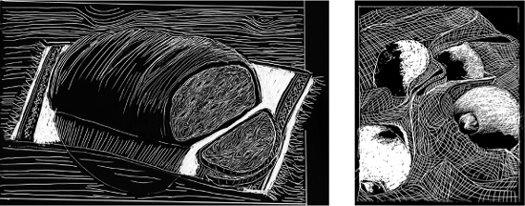

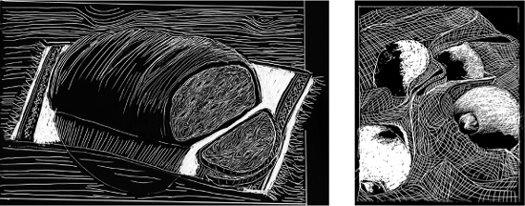

It was just such a wagon that gathered us up to start the journey to America. There were six of us and two young men who were going the 30 odd miles with us to the nearest railroad at the town of Vinnitsa. Our baggage, packed in sacking, was squeezed into the rear of the wagon and tied with ropes. My mother carried a basket of food, and there was also an especially heavy linen sack with slices of rye bread, soaked in beer and dried. Eaten with tea this would often make a meal on our long journey. There were also goose cracklings, very dry, in an earthen crock wrapped securely in sacking and packed in a basket. How we later appreciated this delicacy when food was scarce on board ship! Lemons were each carefully wrapped in sacking and put in with apples in a coarse linen bag. This was all the food we took; it was only intended to supplement the other food we would get on the way. Little did my mother dream how basic and precious it all would turn out to be, as our journey stretched into many weeks.

The wagon stood in front of my grandfathers house on what was the main street of the town. The street was wide, unpaved, rutty. In the spring it was a stream of mud, in the summer inches of dust, in the fall mud again, and in the winter covered by snow and sleet. It was lined with ugly one-story wooden houses, set close to each other, without gardens or shade trees. There was a kind of a boardwalk that ran along the front of the houses the length of the street for about 300 yards and then ended abruptly in ragged bushes and weeds. And beyond was the river, a small, sluggish, but rather clear, stream.

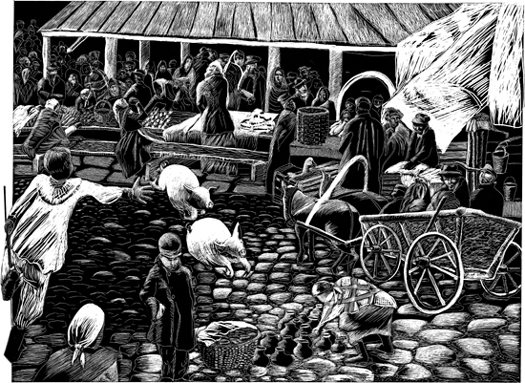

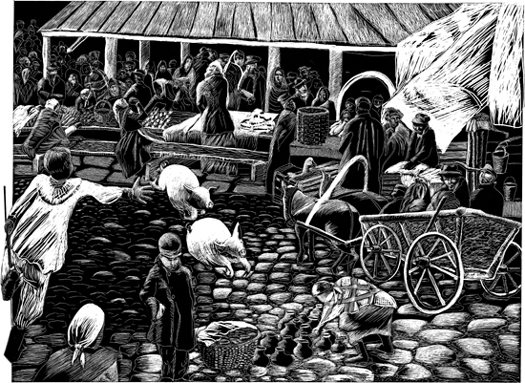

The opposite side of the street had fewer houses, unpainted, rickety. The spaces between were wider, and in them were set up crude stalls where women sold flour, herring, dried fish, apples, and other fruit in season. Some of the houses had cellars that were occupied by shoemakers, tinsmiths, coopers, carpenters, and other craftsmen. There was always activity on that side: the tap-tap of the shoemakers; the distinct hammer of the carpenter; the clang of copper and tin.

On warm days the women dozed at their wares. Sometimes there was a sad awakening as a dog snatched a fish, or a pig on the loose would upset a trough. Then several women would jump up and take after the animal. The craftsmen would pop out of their doors in commiseration and sympathy, and I would hear imprecations and doleful comments. Sad, how sad life is! How hard it is to make a living! So much struggle for a piece of bread!

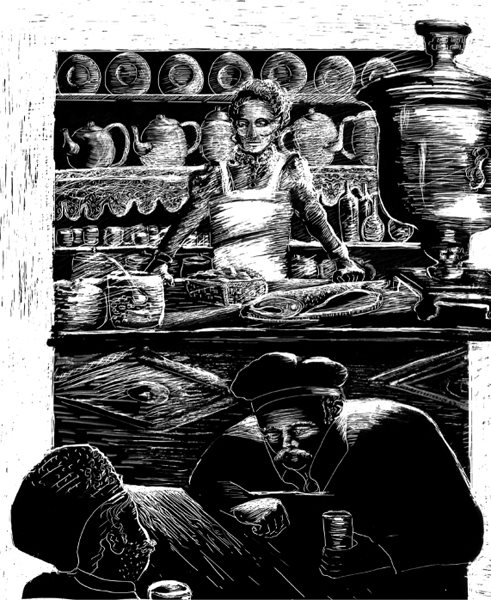

My maternal grandparents ran a kind of combination liquor store and tearoom. The large front room of their house contained shelves where the bottled vodka with its government seal was displayed. The stock was meager, and my uncles, young men in their twenties, were always running out for more stock. The tearoom part was in the hands of my grandmother and my two aunts, both younger than their brothers. They served mostly fish, both hot and cold, and tea. Ordinarily there were rarely more than four people, usually peasants in from the country, eating at the long pine table. But on days when a company of soldiers was going through the town, or when recruiting was going on, the place was full. The liquor could be opened and drunk outside only. But there was quite a bit of swigging going on at the table from a small bottle.

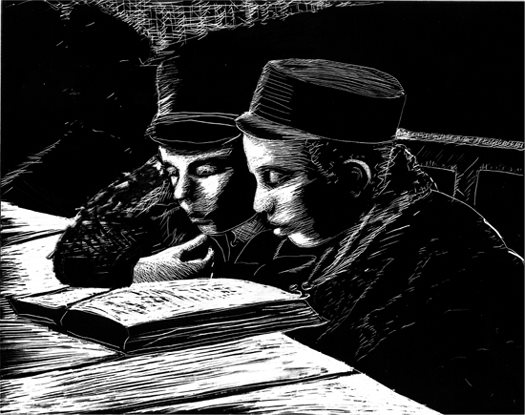

How could that family of seven, all adults except the youngest, live on the small proceeds of the business? There was no other income. My uncles were fairly well educated, but trained for nothing useful. They gave lessons in reading and writing, one in Yiddish, the other in Russian, at 50 kopeks a lesson. There were, however, few lessons. Most educated Jewish young men and women tried to give lessons, and too few could afford them. One of my aunts, the younger one, not quite twenty, was well versed in Hebrew. Whatever her aspirations were, teaching could not have been one of them. For women did not teach Hebrew in that little townRussian, yes, but not Hebrew. That was restricted to men, regardless of how ill equipped they may have been for it. There was nothing for women to do outside the home; the scant business of the tearoom was the only work there was. The girls just waited to be married.

Next page