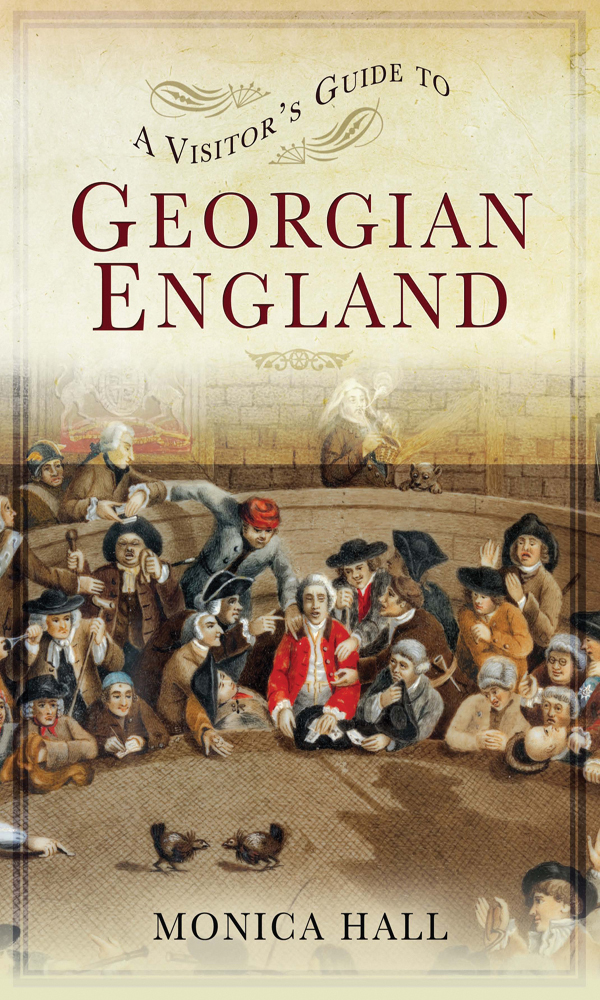

A Visitors Guide to Georgian England

A Visitors Guide to Georgian England

Monica Hall

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

Pen & Sword History

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Monica Hall 2017

ISBN 978 1 47387 685 9

eISBN 978 1 47387 687 3

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47387 686 6

The right of Monica Hall to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Chapter One

How to be a Georgian

S ince H.G. Wells wrote The Time Machine in 1895 people have dreamt of time-travelling, no matter that modern science raises some very trenchant objections to its possibility. It captures the modern imagination rather as Heaven did for our ancestors. Who has not daydreamed about, say, nipping back to Tudor times to inform Henry VIII that it is the father who determines the gender of the baby? He wouldnt listen of course, and one would probably need a way of escaping back to the twentyfirst century instantly to avoid the Tower, but that is not the point. Equally fascinating, and very problematic to the more thoughtful would-be timetraveller, are the consequences of interfering with history, as encapsulated by Zemeckis and Gales 1985 film, Back to the Future . To do so might preclude the possibility of ones own birth, which would be the ultimate own goal.

I, personally, would like to spend some time among the Georgians. It seems to have been an era of considerable energy and optimism, combining scientific and philosophical progress with the sort of rather unruly social behaviour that we can only wistfully dream about today. We might not actually want to witness a public execution as they evidently did, but who has not secretly wanted to throw rotting fruit or vegetables at the sanctimonious people in public life who tell you what you should think, or how you should live? If you were a Georgian, you would have thrown it, had you had the opportunity. Forcefully.

Above all, the Georgians were optimistic risk-takers. They had to be, as there was no other way to live. They often did dangerous work in which the risk of tetanus or sepsis from wounds was ever present. The Industrial Revolution was underway, bringing both investment and employment opportunities and the risk of losing money. Sanitation and drinking water was dubious to say the least, especially in towns and cities, and medical help were equally haphazard. Childbirth was still both inevitable and dangerous. But, most importantly, the Empire-builders were on the move.

As a nation, they were not faint-hearted. Those working for the East India Company faced a long and arduous journey in what we could consider ridiculously small and insanitary sailing ships, and when they got there they had to uphold the white mans burden by enduring tropical weather, parasites, and diseases while persisting with absurdly unsuitable European clothing. Their womenfolk had to struggle to remain British household mistresses while contending with unfamiliar food, ailing children, inscrutable servants, and termites and mould attacking their homes. And they did, even though they had to face the deadly trinity of smallpox, cholera, and plague, and the fact that they died at twice the rate of fellow civil-servants in England. Unfortunate soldiers in the East India Companys private armies died like flies. The Georgians, however, had a sense of opportunity and adventure that has evaporated since the vicissitudes of the twentieth century.

Today, one often feels that life in the West is a competition to see who can live the longest if one obsesses about diet, exercise, and a somewhat depressing level of self-denial, although nobody has yet convinced most of us that staggering into our late 90s is such a very good idea. The Georgians, who did not enjoy our life expectancy anyway, would have thought this a daft objective. Far better, they seem to have thought, to live hard and well in whatever time was available to them. Besides, the established religions that they were slowly coming to doubt did, at least, offer some redemption on their death-beds.

One real difference between the Georgians and their Stuart and Tudor ancestors, however, was the rationality of Enlightenment learning and thinking. Eighteenth century men (and women) really did pay considerable attention to the gaps in their traditional knowledge, and the scientific discoveries and philosophical thoughts emerging during their era. Largely, they seemed to have valued both thought and experience over superstition and undemocratic authority. This makes them modern indeed. In between such highbrow thoughts, however they liked to have fun , and this is their most endearing quality.

In order to understand the Georgians it is absolutely necessary to anchor their era in the context of what both went before, and came after, them. We can only but try to feel and understand the life and expectations of the eighteenth century. For the adventurous time-traveller, this book tries to offer an insight into their lives. They had great opportunities as well as considerable difficulties, and they obviously decided that the former should overcome the latter.

Anyone wanting to visit Georgian Britain might be rather surprised to find it relatively easy to fit in, because the Georgians, or at least those living in the cities, were rather familiar in their outlook and interests. Such an experience would depend, of course, on whether one were a man or a woman, and whether one were going to attempt to bluff it out in high society or virtuously empathise with life among the rural poor. Like most societies, the Georgians believed in equal opportunities for ordinary women when it came to doing the work and, although only men could do the heaviest jobs, the average woman would have had to be a lot tougher and physically stronger than most of us. At the beginning of the eighteenth century most people were working the land without the benefit of machinery or power. By the end of the eighteenth century, all this was in the throes of radical change.

But during the eighteenth century, the majority of the population was still mostly illiterate, somewhat superstitious, and beholden to employers or landlords. They were also subject to childhood diseases, and infections like tetanus and tuberculosis. Their diet, however, was not so very bad, especially compared to that of the poorer, and more numerous and urban, Victorians. It was probably neither as tasty nor exciting as ours, but more useful in terms of basic nutrition than we would generally suppose. A nourishing breakfast was often eschewed in humble households, due to practical reasons concerning dawn and the demands of livestock, but an early midday meal and a substantial supper were both absolutely necessary. The greatest responsibility of women was to ensure that the workers were well fed. Physically hard-working men needed at least four thousand+ calories a day, compared to our less than three thousand. Many of these calories were absorbed through bread, prepared in the local bakery, which has always been the human staple, together with rice in the Far East. Our ancestors knew the value of carbohydrates.

Next page