An example of great determination, to achieve what is becoming harder all the time, an adventuring first

SIR RANULPH FIENNES

THE REMARKABLE TRUE STORY OF A BOLD AND FEARLESS YOUNG ADVENTURER.

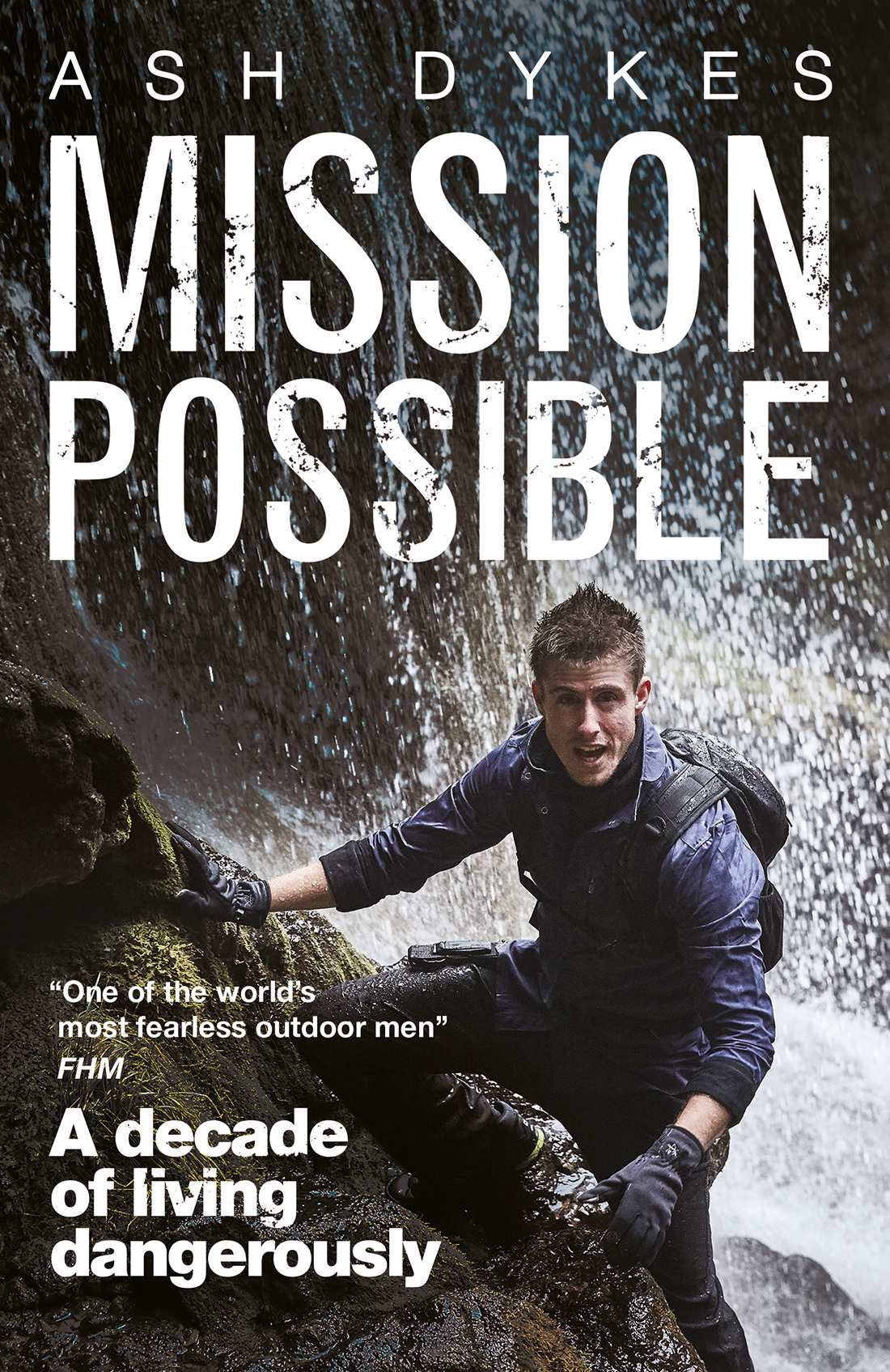

At the age of 23, Ash Dykes became the first person to walk, solo and unsupported, across Mongolia. His journey took 78 days and saw him trek over the Altai Mountains, the Gobi Desert and the Mongolian Steppe. It was an expedition filled with danger and extreme conditions. He almost didnt make it.

A year later, Ash spent more than five months traversing the length of Madagascar via its eight highest peaks and through the civil unrest that was brewing in the south. It was another world first.

In Mission: Possible, Ash reveals the spirit, planning, training and sheer determination that went into these two record-breaking feats. Along the way, we discover how a young man from Wales transformed himself into one of the worlds most acclaimed and exciting young adventurers. It is an inspirational story.

ASH DYKES was born in St Asaph in North Wales in 1990. He has learned how to survive in the jungle with a Burmese hill tribe, worked as a master scuba diving instructor and trained as a Muay Thai fighter. He has won the coveted Adventurer of the Year award and is often requested to speak for corporates, schools and colleges. His exploits have won him recognition in a wide range of publications and TV shows, as well as an invitation to 10 Downing Street. He is an inspiration to his tens of thousands of followers from all over the world.

MISSION: POSSIBLE

A decade of living

dangerously

by ASH DYKES

Published in 2017

by Eye Books

29A Barrow Street

Much Wenlock

Shropshire

TF13 6EN

ISBN: 978-1-78563-046-0

Copyright Ash Dykes 2017

Cover design by Shona Andrews

Layout design by Clio Mitchell

The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE: Gobi Desert, 2014

Sharp stones on the hard, sandy ground where I lay poked like nails into my back. Just a few inches above me was my steel trailer with my tent and other kit loaded on top, and I tried to avoid touching the hot metal. Id shuffled underneath it to shield my upper body from the burning sun, but my legs stuck out the end and felt as if they were melting. I imagined how I would look if there were anyone around to see me, but there wasnt anyone for miles: in my minds eye, the camera panned out into the sky over an empty expanse of bright pale desert until I was an insignificant speck, a dot gradually fading from view.

I put the water bottle to my blistered lips. Id been daydreaming of cold, clear, fresh water, babbling brooks, gushing taps but the dregs left in the bottle were as hot as tea and tasted sour. The heat was relentless it must have been over 40C and Id been trekking since morning, weak and semi-delirious, my eyes tired from searching the horizon for signs of a settlement. By this time I had been walking for 43 days through the Gobi; dragging the 18-stone trailer through sand had been tough from the beginning, but now every step was demanding. The last food Id eaten hadnt spent much time in my system, and my body was running on empty. My mind had been wandering as my body struggled on.

I had ventured into the Gobi Desert, known as the harshest desert in the world, earlier than anticipated, taking a route without confirmed water sources. Although Id made it through that section Id had to ration my water for a few weeks and the dehydration had been getting worse without my feeling any symptoms. Now, in the hottest and worst part of my route through the desert, where there were no water points for several days at a time, it had all hit me and I was suffering the consequences in the most severe way. I remembered the eerie skeletons of camels Id walked past in the middle of nowhere. The thought entered my head, a sudden clear thought emerging from the fog, that this could be my impossible day: the day I might not succeed, the day my expedition would fail the day I could die.

People had said it was impossible to cross the country this way, walking all the way alone through mountains and desert and steppe No-one had done it before. It just wasnt possible, they said. Were they right?

No . If I could just make it 100 more metres, I could rest again, and if I could keep going like this, I would make it to a settlement, however long it took, and someone would give me water. I had to believe it. Somehow the need to prove people wrong, to prove that I could do it and perhaps just the will to live galvanised me to pull myself up. My muscles ached but I gritted my teeth against the pain, cursing. Must continue , I said to myself, no matter what . Determined to keep pushing on, I broke the goal down into small steps. Step by step.

It was resilience and mental strength, I believe, that got me through these days, making it all possible again. It was also thanks to my previous experience. I dont know if Id have been able to walk across Mongolia if I hadnt done everything that came before. Every step of the journey of the previous years had built up to a powerful force that helped me survive.

Crossing Mongolia solo and unsupported, becoming the first person known to have done so, was my first big expedition, which I completed at the age of 23. Several years before, Id decided I wanted to go into the unknown, throw myself far out of my comfort zone, push my personal limits, experience as much as I could and see what was possible. My insatiable appetite to explore and to challenge myself was there already. To me, that was truly living. But growing up on an ordinary street in an ordinary town in North Wales, it had felt like a crazy idea to make such a huge dream happen.

Part One:

GETTING STARTED

1: Making a mind map and the money to set out

It was still dark when my alarm went off: 4am. I silenced it quickly, wishing I could ignore it but across the gloom of my bedroom I could see the world map, and knew why I was doing this. I braced myself for the cold as I flung off the bedcovers, grabbed my backpack and crept into the hallway, avoiding the creaky floorboard, trying not to wake Brodey . Within five minutes I was opening the back door and jumping on my bike. The wind blew off the Irish Sea and rain slapped me in the face. Oh, the joys of winter on the coast of North Wales! The only solution was to cycle as fast as possible, get the heart going and warm up. And remember all the money I was saving by not having a car.

Eight miles later I skidded into the car park at Llandudno swimming baths, locked up the bike and made my way into the showers, turning on the lights and pulling everything I needed out of my bag. The hot water felt good and I could hear others arriving for the early shift. I dressed in the standard polo shirt and shorts, gave Mat a high-five as I passed him in the corridor, and assumed my position at the side of the pool, wrinkling my nose at that familiar smell of chlorine and bodies, ready for a mind-numbing morning of watching the regulars swim up and down. Up and down. Up and down.