Amelia Earhart, the worlds most famous woman pilot, would be right at home in the twenty-first century. She would exult over womens freedoms. She would be fascinated by outer space and eager to fly there - if she hadnt already visited the moon. She would be as visionary, innovative, courageous, and modest as she was in the days before her disappearance in 1937.

Her 1928 flight as a passenger from the United States to England made her the first woman ever to fly the North Atlantic, her 1932 flight made her the first woman ever to fly it twice and to fly it solo. These are the most impressive of many records she broke and then exceeded during her meager nine-year career. In life, she captured the attention of the world with her daring aerial exploits as well as her distinctive qualities, and in death she continues to hold attention.

Amelia Earharts boyish good looks and casual manner pleased admirers. She so impressed her publisher that in time he proposed to her and publicized her so well she became a standard of unconventional beauty. The leggy strength of her slim body, the direct glance from clear blue eyes, as full of wonder as a childs, the cropped hair, the cheerful grin, the breezy manner - the clichs multiplied and were widely imitated by girls and women who adopted the Amelia Look.

She was happiest alone in the air or in greasy coveralls at work with the men on her beloved Lockheed. After the 1928 flight, she gathered crowds everywhere she went, adoring fans who came to gaze, to listen, if possible to touch, and who applauded her message: Flying is safe, and women make good pilots.

Her end came on July 2, 1937, somewhere in the vicinity of remote Howland Island, almost 2,600 miles from Lae, New Guinea, 7,000 miles short of making her the first woman to fly around the world and twenty-two days before her fortieth birthday.

Certainly the circumstances of her disappearance added drama and preserved her fame at its peak. Whatever happened to Amelia Earhart? became a mystery which has fascinated searchers, writers, sensationalists, theorists, and many others ever since. No one knows, and it is unlikely anyone will ever discover the truth of that day in the vastness of the Pacific Ocean.

In reality, she was a heroine who defied convention. At a time when women were restricted to domesticity, she fled from it. When they were considered only fit for motherhood, she refused it. When fidelity was a convention of marriage, she denied it. When business was dominated by men, she competed. When records were established, she broke them. And when men flew, she flew too.

Not everyone loved Amelia Earhart. She was said by some friends and all her foes at one time or another to be withdrawn, cold, greedy, self-serving, patronizing, arrogant, and supercilious, among other epithets. Jealousy and resentment motivated some women and some men pilots against her; some of the family thought her too nonconformist to be acceptable, although all of them doted on gossip about her and a good many became her financial dependents.

Amelia had the good fortune to be of the correct age and gender as well as having the dedication to aviation when an American woman pilot was required for the 1928 flight to England.

For George Palmer Putnam, of the old and respected publishing firm, she was the golden girl. He sold her to the world when he published her first book, 20 Hrs. 40 Min., scooping other publishers as he had the year before when he brought out We by Colonel Charles A. Lindbergh. A year later the publisher divorced his wife, the mother of his two sons, and married his client.

Amelias sister, Muriel Earhart Morrissey, when any question of sibling rivalry was mentioned to her, strongly denied it. Deeply devoted to her own family, Muriel wrote Courage Is the Price, her story of two little girls born of loving parents. One grew up to be a world-famous pilot and the other stayed home to raise a family.

Their mother, Amy Otis Earhart was born with a generous spirit and great physical stamina, although her hearing was impaired from the age of sixteen. Raised in a social milieu which held fast to its standards and conventions, she never remarried after her divorce in 1924 from Edwin Stanton Earhart, yet she was daring enough and loving enough to support Amelias desire to fly. She gave part of the money for Amelias first plane, and later was a fearless passenger with her daughter at the controls. Frequently Amelia related during a lecture how her mother would read a book when they were flying together.

Amy was staying at Amelias North Hollywood residence when her daughter vanished in 1937, and she remained there for some time afterward, with frequent but short visits to Muriel and other relatives in the East and Midwest. A number of times she moved temporarily to Berkeley, California, and in July 1949, she became a paying guest in an old brown-shingled house growing out of a canyon hillside behind the town. Every evening at sunset she went to stand on a balcony, gazing west past the University of California and the bay of San Francisco toward the Pacific, where she expected Amelia to appear from her round-the-world flight. No one knows when Mrs. Earhart accepted the fact that Amelia would never return. After a year in Berkeley, she moved East to live permanently with Muriel in Medford, Massachusetts, where she died on October 29, 1962, in her nineties.

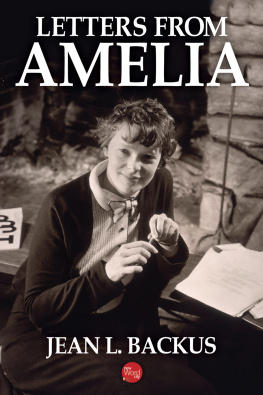

Left behind were four cardboard cartons of letters and miscellanea, which remained undisturbed and unclaimed until the owner of the brown-shingled house died in 1975. Her heir then called a second-hand book dealer to evaluate the large library, and other items in the attic. When he saw the cartons and learned they contained material relating to Amelia Earhart, he offered a large sum to buy them unopened.

As a friend of both the owner and the heir, I was then asked to examine the contents before the cartons were sold. I discovered that Mrs. Earhart had saved everything, from her own wedding invitation to notes found in floating bottles after Amelias disappearance. She saved telegrams, get-well and Christmas cards, Easter greetings and gift tags, wedding and birth announcements, and newspaper clippings.

Jumbled in every which way were more than a hundred long letters and short notes from Amelia to her mother. Filled with family gossip, itineraries, financial discussions, comments on religion, birth control, and marriage, the letters begin with a note from Amelia at four years of age to her Grandmother Otis. They end with what may have been the last written word to her mother in 1937. Since she rarely dated her letters except by day of the week, and since some postmarks were torn off or smudged, cataloguing the collection and segregating other letters and material in the four cartons was difficult and took more than eight months.

When complete, the collection presented the human side of a great woman with all her virtues and imperfections, a woman of enormous public acclaim and heroic accomplishment, and a woman who never failed in her obligations as a devoted daughter, a supportive sister, and a liberated wife.

On July 24, 1901, her fourth birthday, Millie wrote her first letter in childish print:

DEAR GRANDMA. I GOT A STOVE WITH A TEA KETTLE AND PAN. A DOLL AND SOME BOOKS. I LOVE YOU AND THANK YOU. YOUR LOVING MILLIE.

Millie was Amelia Mary Earhart, who one day would be the most famous woman pilot in the world.

Grandma was Amelia Harres Otis, Amelias namesake and wife of Judge Alfred Otis of Atchison, Kansas. These maternal grandparents were socially prominent and taught Amelia and her younger sister Muriel Grace the social expectations of their class. Grandpa Otis traced his proud New England heritage to James Otis, the man who proposed the Stamp Act to Congress in 1765, an event said to have started the American Revolution. The Judge was now retired from the bench but still president of the Atchison Savings Bank and immensely wealthy from shrewd land speculation.